The Nerdwriter: YouTube Channel for Art Lovers

If you are a naturally curious person and above all an art lover, Nerdwriter is a complete channel to kill all curiosities and learn a...

Dévra Taboada 21 October 2020

It’s easy to notice the widespread presence of media arts in almost all aspects of our daily lives, but that wasn’t always the case: when new media were only on the rise, artists like Nam June Paik paved the way for technology to be incorporated into the art world. Paik was the first to appropriate video as an artist’s medium and during his prolific career, he not only embraced and influenced the redefinition of television but also expanded the definition of art making.

Nam June Paik, Untitled, 1993, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Nam June Paik (1932-2006) is known today as the father of video art: he pioneered the use of film in his artistic language and developed an innovative practice transgressing pre-existing borders and rules. Born in Korea in 1932, he then moved to Japan, Germany, and finally the US in 1964, where he became prominent within artists’ circles in New York.

Art as we know it today wouldn’t be the same without Paik’s input in the previous century: here are 5 works by him to introduce you to Nam June Paik and his experimental, yet playful world filled with technology and moving images.

Nam June Paik and his TV Buddha at Projects: Nam June Paik, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA, 1977. Photo by Eric Kroll.

Paik’s iconic video installation TV Buddha consists of a statue of the Buddha placed before a video monitor and a camera above it that transmits the image of the god into the screen in real-time. Since 1974 Paik has done many variations of this work that differ slightly, but they all resemble the initial setup of a statue looking at its own image displayed on a TV screen. Here, Paik makes a direct usage of Asian imagery: the theological and metaphysical construct of this installation is, whether consciously or subconsciously, Buddhist, based on the comparisons with classical Buddhist art, which Paik was familiar with.

What emerges is the juxtaposition of the modern and historical: Buddha is trapped in the closed-circuit loop of his own reflection on a TV screen, being both the viewer and the viewed. Paik explores the theme of meditation and Zen Buddhism by combining technology with tradition, but also raises questions about vanity and society’s self-absorption driven by mass culture and technology.

Nam June Paik, TV Buddha, 1974, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Electronic Superhighway is an extremely large installation consisting of over 300 tv screens, 50 VHS players, 3750 feet of cable, and 575 feet of colored neons. All of them form a map of the United States, each state represented by a different video clip. This techno-sculpture is overwhelming and dominating the space it occupies with its audio, visual media, and neon flashing lights: there is no way to concentrate on one aspect of the work, as it gets instantly dimmed by others. It is also between the real image of the United States and the virtual reality of the media.

It is Paik’s vision for the future: information and experience available from electronic media. You no longer have to leave your house to discover Oklahoma, which is now defined by technology. Paik reveals how that simplifies our ideas and overwhelms us with information, in a way predicting the Internet.

Nam June Paik’s Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Nam June Paik often explored the possibilities of aesthetic values to television’s flickering facade. In TV Garden, Paik created a composition within the new aesthetic discourse. It is a piece you have to literally enter and get surrounded by to see its full potential. It’s a real fusion of the natural and the technological: little video monitors are hidden amid live plants. They are all playing Paik’s 1973 Global Groove, a montage of performers from around the world. In a way, TV Garden set a new standard for immersive, site-specific installations using video. It was a blueprint for other room-sized installations we might see in museums today.

Nam June Paik, TV Garden, 1974-1977 (2002), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf, Germany.

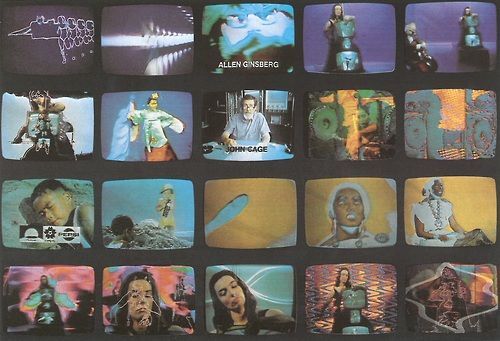

According to Paik, global communication was shaped by mass media and technology. In his film 1973 Global Groove, Paik uses commercials, performances, and video clips from all around the world, juxtaposing them into one – creating controlled chaos and suggesting a nonsensical layer to the channels of global TV. It is postmodern in form, conceptual in terms of strategy, and standing as a statement on video, television, and global culture.

Nam June Paik, Global Groove, 1973. Pinterest.

Paik’s first exhibition Exposition of Music – Electronic Television was held in 1963 at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany. By that time he had already experimented with video and sound; Participation TV was the result of those experiments. The idea is quite simple: the viewer’s speaking sound is transformed into a line pattern on a TV screen via a microphone. Paik manipulated electronic circuits inside the TV, adjusting them freely to his own needs. Once again, the boundaries are broken: the viewer’s participation and engagement are necessary to see the results, bridging the viewer and the artwork itself.

Nam June Paik, Participation TV, 1963/1998, Nam June Paik Art Center, Yongin, South Korea.

Nam June Paik’s input and creativity has shaped the art as we know it today. With technology and moving images literally surrounding us everyday in our lives, it’s good to remember about him and continue his legacy.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!