12 Best Shots of the World Press Photo 2024 Exhibition

The World Press Photo Exhibition is a renowned annual event showcasing some of the most impactful visual photojournalism from across the globe.

Nikolina Konjevod 10 February 2025

Nan Goldin is an American photographer. She is just as famous for her art as she is for social activism, particularly around gay and transgender sub-cultures and also the ongoing opioid addiction epidemic in the USA. Discover her photographs.

Documenting moments of intimacy is the driving force behind Goldin’s work. Perhaps her most famous piece is The Ballad of Sexual Dependency from 1986. This is a slide show of around 700 images, set to music, showing Goldin’s family and friends within gay culture. Goldin’s work is about being alive, it is a confessional commentary on every day, without a censor and without soft focus or photoshop. It is a direct expression of her feelings about the world she inhabits. There is no veneer of glamour, just Goldin’s truth.

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, NYC, 1983, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Within these photographs, there is love, but also an awareness of death and loss. Many of the people Goldin captured on film are not here anymore due to drug overdose or HIV/AIDS. Goldin was very aware of the stigma around gay culture in America. The Stonewall riots of 1969 were a recent memory within the gay community, where constant police raids and harassment led to a series of protests and the transformation of the gay liberation movement in the USA.

Nan Goldin, Cookie and Millie in the girls room at The Mudd Club, NYC, 1979, New York, NY, USA. AWARE.

Some of the images are haphazard, some are blurry, some are taken in rooms that are either too dark or overexposed by a flash. Some are cluttered with the ephemera of daily life. That is one of Goldin’s trademarks. She wants to photograph in the moment, so setting a scene, selecting props, or checking light levels isn’t on her radar. Her work is immediate and instinctive.

Nan Goldin, Nan on Brian’s lap, Nan’s birthday, NYC, 1981, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

My photography has come out of emotional need not aesthetic choice. I came from a family and a culture, that was based on “don’t let the neighbours know”. I wanted to let the neighbours know.

Interview with Sean O’Hagan, The Observer, 23 March 2014.

When Goldin was 11, her rebellious older sister Barbara died of suicide aged 19, a story her bourgeoise parents wanted to hide and cover up as an accident. This trauma must have been a key driver in Goldin’s insistence on truth, however painful that might be. Her stance is brutally anti-revisionist and unapologetic.

Goldin left home very young – she reports being 13 or 14. She attended a free school, built around personal freedom with a curriculum chosen by the children themselves. A donation of cameras from the Polaroid company led to Goldin’s discovery of photography – something that became her life-long passion.

Nan Goldin, Heart Shaped Bruise, 1980, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

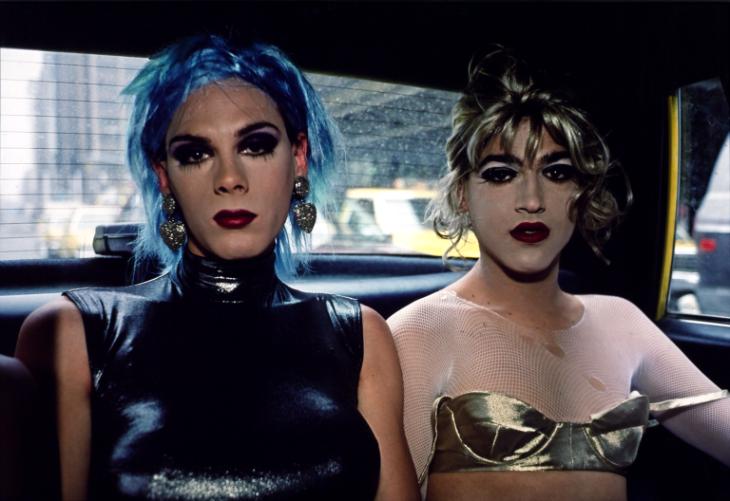

At 18 she was living with a group of drag queens, and she wanted to record their lives. She said she loved fashion photography and wanted to get them on the front cover of Vogue. College classes in studio photography did not suit Goldin at all, and instead, she worked alongside Henry Horenstein. He introduced her to the work of photographer Larry Clark, who became a huge influence on her. She cites Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground as sources of influence too.

Goldin spent a couple of years working at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but technological perfection was still not her focus. She moved to New York City, documenting the post-punk new wave music scene. She was especially drawn to the hard-drug sub-culture around the Bowery neighborhood.

Nan Goldin, Jimmy Paulette on David’s bicycle, 1991, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, NY, USA.

Bill Clinton (ex-American President) blamed Goldin for inventing and glamourizing “heroin chic”. It was a 1980s fashion for super-skinny models, with grunge clothing, blank faces, pale skin, and stringy hair. But Goldin strongly refutes this – she was horrified by the use of this imagery in fashion photography. She herself had been pulled in by the sheen of glamour and coolness associated with drug use, but her experiences showed that it could be a cruel and destructive world.

Nan Goldin, Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC, 1991, Tate, London, UK.

Photographer Diane Arbus was her contemporary, but Goldin did not like Arbus’ photographs of transvestites. She felt that Arbus was taking a voyeuristic, controlling approach, rather than settling in and letting the models set the tone and pace. Goldin saw transvestites as a third gender, to be celebrated and respected, long before such ideas came into popular culture. Goldin was completely immersed in this community and has said she was in love with a drag queen herself. “This is my history, my family”, she claimed.

When I look at a queen I don’t see a man dressed as a woman; I see a merger of a third gender. I see a kind of freedom.

Bomb, 1 October 1991.

Having left home so young, drifting on the outskirts of society, Goldin had found herself in a counter-culture world of drugs, alcohol, and sex. She says that she had a romantic notion of being an addict. Part of her reason for photographing everything around her was to remember it, to know what had happened, as the drugs and alcohol impaired her memory. She later sought rehabilitation, which was a long and challenging journey.

Nan Goldin, Nan one month after being battered, 1984, Tate, London, UK.

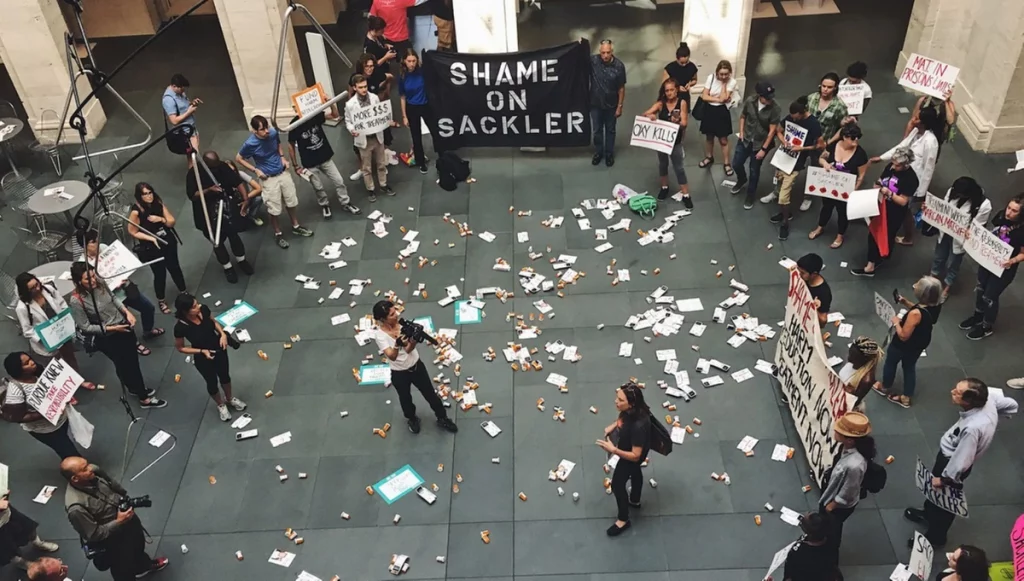

Never averse to controversy, Goldin is the founder member of PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). She has taken on big business in her fight against opioid addiction. After a wrist injury in 2014, Goldin was prescribed Oxycontin, a legal painkiller to which she became addicted. Purdue Pharma, the company that has made billions of dollars from the drug, was owned by the Sackler family – known mostly for their extravagant financial contributions to the arts. Investigations have shown that the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma knew about the addictive qualities of Oxycontin, and also knew it was being traded as a street drug, but did not take any action.

Nan Goldin, Shame on Sackler demonstration, 2019, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, USA. PAIN.

The opioid crisis in the USA has claimed half a million lives. Goldin argued that philanthropy did not wipe the stain from the Sackler family name. She organized protests at major arts venues, including the Guggenheim, MoMA, and the Louvre, and threatened to withdraw her works from galleries that took money from the reputation-laundering Sacklers. The scandal made it to international news and Goldin forced the art world to sit up and take notice.

I didn’t care about “good” photography, I cared about honesty.

Interview with Sean O’Hagan, The Observer, 23 March 2014.

Nan Goldin, Picnic on the Esplanade, Boston, 1973, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, NY, USA.

Nan Goldin’s work and life are inseparable. Her current work is still about love and intimacy, but her immediate circle is her family life and her friends’ children. Although the spark of her activism still burns brightly.

Perhaps the reason why Goldin’s work speaks to us is that we all take blurry, off-center snaps – at family events, at parties, at home, just to capture the moment. She believed that if she photographed anything or anyone enough, she would never lose them. Isn’t that us, with our albums and Instagram moments? Goldin’s work through 1980s New York was the story of a generation. A generous and loving contribution to the LGBTQ+ community, to the victims of the opioid crisis, and to all of us.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!