The National Gallery in London: Where to Start?

Having lived in London for the past three years as an art lover, I have had more than my fair share of questions about where to “start” at the...

Sophie Pell 3 February 2025

15 June 2021 min Read

The recent debut of the New York City Triennial 2021 exhibitions at the Asia Society Museum on the Upper East Side and El Museo del Barrio in East Harlem feature over eighty artists. Consistent with the missions of these NYC institutions, the Asia Society Triennial: We Do Not Dream Alone features internationally-based artists of Asian descent, and Estamos Bien – la Trienal 20/21 presents Latinx artists living and working in the United States and Puerto Rico. As both of these inaugural triennials were conceived pre-pandemic, they opened to the public at a watershed moment in time. While the events of the past year are acknowledged throughout, these expansive exhibitions prioritize the issues, iconographies, and ideologies endemic to marginalized populations and overlooked subcultures.

The Asia Society Triennial rolled out as two successive exhibitions, Part I and Part II, featuring 40 artists at various stages of their careers, working in a range of disciplines and scattered across the globe. We Do Not Dream Alone, pays homage to Japanese-American conceptual artist Yoko Ono.

“A dream you dream alone may be a dream, but a dream two people dream together is a reality.”

Yoko Ono, Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings by Yoko Ono, 1964.

Whether one would like to think of the past year as a shared dream, nightmare or a mixture of both, this spirit of unity and empowerment through art marked the inauguration of the Asia Society Triennial. This sentiment resonated across New York City since its reopening last fall. Just a few blocks from the Asia Society Museum, the words of Yoko Ono were boiled down to “DREAM” and “TOGETHER” and blown up to epic proportions for billboards that appeared on the facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art to mark its own reopening in September 2020.

For Part I of the Asia Society Triennial, Syrian artist Kevork Mourad’s (b. 1970) installation of a fabric tower, Seeing Through Babel, filled the central space of one gallery. The tower, consisting of six concentric circles of print-covered fabric suspended from the ceiling, swayed in response to visitors circumambulating this delicate structure. Impressive in scale, Mourad’s whimsical tower is a flowing symbol of unity meant to counter the Tower of Babel allegory and the discord embedded within difference.

In the same gallery space and for Part II, six freestanding walls were installed by the Indian artist Abir Karmakar (b. 1970). These walls are covered in hyper-realistic renderings that meticulously document the interior spaces of homes in India today. The objects in these paintings make subtle reference to the colonial history of the Indian sub-continent. The idiosyncratic dimensions of each wall, interrupted by doorways that allow one to walk through the paintings, are based on the interior spaces of former residential buildings located on Governors Island, just a short ferry ride from Manhattan.

Today, Governors Island is an outdoor recreational space for New Yorkers, but it previously served as a military base and army outpost for a small community of residents throughout the mid-1990s. This small island has changed hands several times since the 17th century, beginning with the indigenous tribe of the region, the Lenape, who were forced out by the Dutch. It was then taken over by the British who begrudgingly handed it over to the newly formed United States. Karmakar’s paintings, through subject and size, fuse together two histories, indelibly marked by colonialism.

Parts I and II of the Asia Society Triennial featured Korean artists grappling with the division of the Korean peninsula. Each artist has sought ways to covertly penetrate this divide and collaborate with anonymous North Korean participants.

Kyungah Ham (b. 1966), who is based in Seoul, went through great lengths to smuggle instructions into North Korean workshops for the production of embroidered works. These beautifully crafted embroidered works of silk threads and cotton depicting chandeliers are made entirely by individuals whose identities remain unknown to the viewer. The artist of What you see is the unseen/Chandeliers for Five Cities, lists the middle man, smuggling, bribe, tension, anxiety, censorship, and ideology as the materials that went into the production of these works. Beneath the surface of these colorful and aesthetically pleasing works of art is a psychological drama of despair over the partition between North and South Korea.

Similarly, Mina Cheon, a North Korean professor of Art History, (b. 1973), created What is Art, What is Life? under the alias Kim Il Soon as a means to connect with actual North Koreans. Posing as Kim Il Soon, the artist recorded lectures on the major movements of Western art history for an anonymous audience in North Korea. These lectures were smuggled into North Korea via USB drives in resistance to the draconian censorship of the regime. At the Asia Society, small video monitors play the lectures of Kim Il Soon, who discusses subjects such as feminism, money, power, food, abstract art while dressed in traditional clothing and with her features enhanced with social media filters, which have become commonplace.

As feedback, a group of anonymous painters in North Korea, responded to the lessons of their professor with a painting after Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Opposite the painting by the “students” of Kim Il Soon is a diptych made by the artist as her alter-ego representative of a collective desire for a peaceful unification.

The subject of The Last Supper is also seen in the work of the Indian artist Vibha Galhotra, who was given an entire gallery for Part II to present the The Final Feast (Staged Photographs). At the center of this highly-produced series is a group photograph that recalls the The Last Supper. This gathering is not about deception or sacrifice but rather the abuse of power and world domination over the majority by an elite few. The participants are about to cut a cake which serves as a metaphor for their division and distribution of the globe into equal parts to be controlled by an exclusive group of individuals. The dystopian content of these photographs are sadly not far from the truth. One cannot help but draw connections to the jarring contrast between the destabilization of many around world who already struggle to survive and the billionaires who have egregiously profited during and from the pandemic.

From the powerful to the empowered, visitors to Part I were treated to an elaborate and very personal altarpiece by Malaysian artist Anne Samat (b.1973). This multimedia installation of a surprising choice of mass-produced household items such as brooms, rakes, and colanders appeared regal and steeped in tradition; this is a sacred altar, one dedicated to the deceased members of the artist’s family. The central figures are the parents represented as king and queen and placed on either side of the artist’s brother who died at a young age. This royal triad is attended to by two smaller figures, the artist and her sister, the only remaining living members of this family. This monumental family portrait is a labor of love and testament to the unbearable grief and eventual acceptance of one’s losses.

Ceramic vessels in the style of ancient Greek pottery are decorated with painted images of tortured and dead bodies. Images of non-European males were sourced from media coverage which, from my American perspective, are understood as victims of the prolonged wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Iranian artist Reza Aramesh’s (b. 1970) installation of the Study of the Vase as Fragmented Bodies for Part II, merges classical antiquity with contemporary subject matter. These non-white/non-European male bodies are decontextualized and fetishized in a manner that amplifies undercurrents of homoerotic sexuality and violence that pervade the history of art. These vessels are also poignant reminders of a general desensitization and acceptance of graphic images portraying the gory violence inflicted upon brown and black male bodies.

Part I included a condensed retrospective of Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander (b.1969). On one wall hung the artist’s magnum opus that marked the completion of her studies at the National College of Arts in Lahore, a work that establishes Sikander as the founder of the neo-miniature movement, The Scroll (1989-1990). Sikander’s mastery of the Indo-Persian miniature painting technique has dramatically evolved over the years, as is apparent in the more recent work on paper shown opposite to The Scroll. No Calm of Consummation (2019) is an example of Sikander’s artistic journey over three decades and her tireless experimentation with traditional forms, language, and animation. In this case, the poetic verses of an Urdu poem are sumptuously scattered across the surface into a visually appealing, yet illegible, composition.

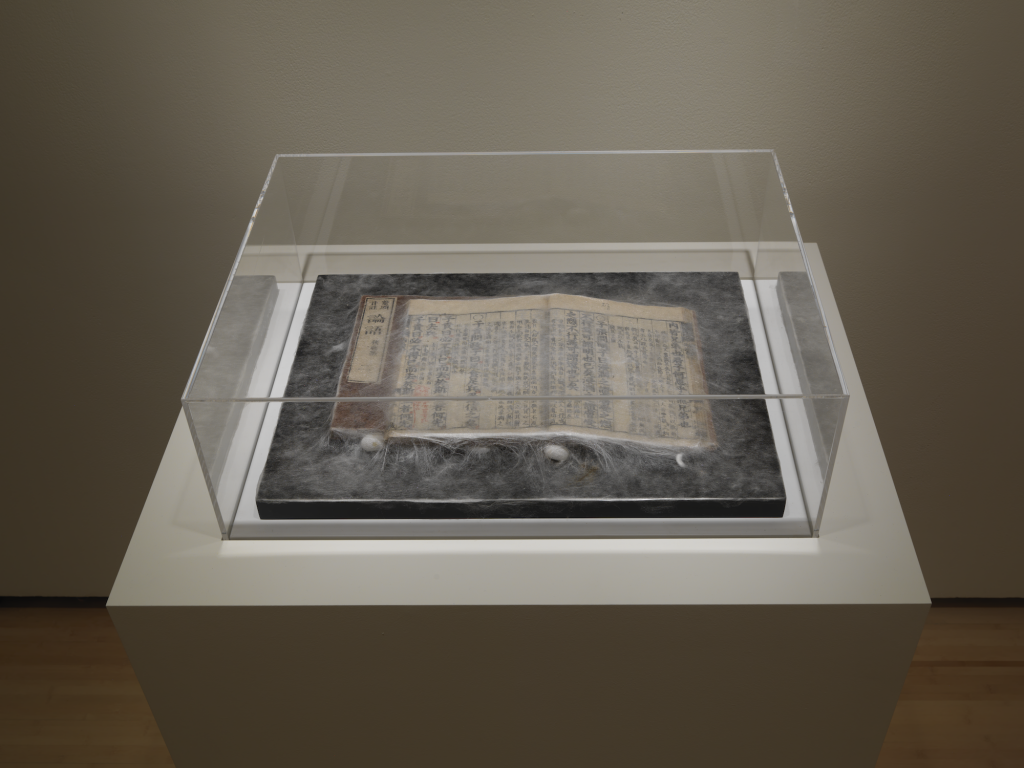

Another artist of long-standing repute, Chinese artist Xu Bing (b. 1955) who is most well-known for his immersive installation Book From the Sky (1987-91), was commissioned by the Asia Society Triennial to make Silkworm Book: The Analects of Confucius (exhibited in Part I and II) in response to the little-known fact that the thoughts of Confucius influenced the founders of the United States of America. The artist let silkworms encase an open copy of the ancient Confucius text with their silk threads. The ancient text shrouded by the ancient practice of sericulture, is suggestive of that which is lost over the passage of time, but moreover the deceptive manipulations of democratic thought and practices across the centuries.

Translation of El Museo del Barrio’s title, Estamos Bien – la Trienal 20/21, is “We Are Fine.” This was borrowed from Candida Alvarez, one of the participating artists in this triennial, whose painting Estoy Bien (2017) commemorated the spirit of resilience and sarcasm by the survivors of the devastation caused by hurricane Maria when is struck the island of Puerto Rico. Estamos Bien encompasses forty Latinx artists working across the United States and Puerto Rico whose contributions honor and make visible the daily struggles and hardships of Latinex communities.

Obituaries of the American Dream by the New York artist Lizania Cruz (b. 1983), born in the Dominican Republic, was launched online ahead of the triennial opening in the galleries, where copies of newsprint were made available for visitors to take home.

“Obituaries of The American Dream invites participants locally and globally, non-im/migrants and im/migrants to share when and how the American Dream died for them.”

About Obituaries of the American Dream by Lizania Cruz.

The project dates, 1931-2020, imply that the death of the American Dream is not a recent phenomenon but one that is ongoing and essentially baked into the country’s foundation. The system was devised for this dream to be unattainable, that justice for all is but a deceptive fantasy and that democracy is perilously flawed in the US.

The installation of two life-sized male figures made of yarn by Los Angeles artist Luis Flores (b. 1985) asks Estamos bien? I was initially unsure if I was witnessing a live performance when I first laid eyes on the very realistic sculptural composition of one male figure seated on the shoulders of his twin, right arm reaching above and trying to grasp the hand of another arm that has broken through the wall. The hand-crochet figures appear surprisingly realistic from a distance, partially due to the fact that they are dressed in identical t-shirts, jeans and Converse sneakers. They are doppelgängers of the artist and, although this is not a live performance, this installation activates the gallery space and transports one to the desperation of migrants risking their lives to cross the border.

The magnified proportions of New York artist Lucia Hierro’s (b. 1987) installation of snacks commonly found in neighborhood bodegas taps into the playfulness of Pop Art; however, it also reminded me of the the limited healthy food options across low-income/minority neighborhoods around New York City. Access to farmer’s markets or grocery stores which prioritize fresh and organic over processed and genetically modified is difficult for many people, especially for those with very tight food budgets. Even though these small business are vital for many, sadly there is no nutritional value in the reproduced snacks of Hierro’s Rack: Platanitos, Rack: Chicharrones, Rack: Corn Chips, Rack: Takis.

Pop Art influences are also noticeable in the paintings of Chicago artist Yvette Mayorga (b. 1991) and Los Angeles artist Joey Terrill (b. 1955). Adopting the technique of icing a cake, Mayorga applied thick lines of bubble-gum pink and other bright colors to her canvases, resulting in luscious fields of imagery drawn from everyday life.

Terrill’s large painting Just What Is It About Today’s Homos That Makes Them So Different, So Appealing? is a twenty-first century update of the the iconic collage by British artist Richard Hamilton that kicked off the Pop Art movement in the 1950s. Terrill is a long-time AIDS activist and educator committed to raising queer and Chicana/o consciousness whose paintings create a context for other stories and life experiences.

The curators commissioned New York artist Dionis Ortiz (1979) to make the massive floor installation of vinyl tiles Let There Be Light for La Trienal. This piece references the artist’s personal history and the training he received from his father in laying floors. Beyond the personal connections are references to both the anonymous manual laborers and the inhabitants of the homes, where this type of mass-produced and affordable flooring is commonly installed. The attainment of a home with such floors is an achievement, one that some would consider realization of the American Dream. But this dream is even further out of reach for many people these days. This is an undeniable fact considering the noticeable increase of migrants living in the streets of NYC and often seen in my own working class and predominantly immigrant neighborhood in Queens.

A minimalist grid of hand-molded clay lunch trays comprise Tabled Remains of Vick Quezada (b. 1979), born in Texas and living in Massachusetts. The craftsmanship employed in the creation of these trays counters the institutional function of this familiar item. Mainly associated with schools, hospitals, and prisons, Quezada’s grid is most striking because it is suggestive of daily routines and meal schedules, primarily within the context of a prison. The range of earth tones across the surface of each tray, first hand-pressed into a mold and then fired in a kiln or pit, reveals a process that ensured no two trays are alike – each tray is a unique work of art. Echoing indigenous practices and traditions and grounded in the earth, Tabled Remains conjures the individual and personal stories of those, predominantly the mass incarcerated, whose daily sustenance is inherently tied to the lunch tray.

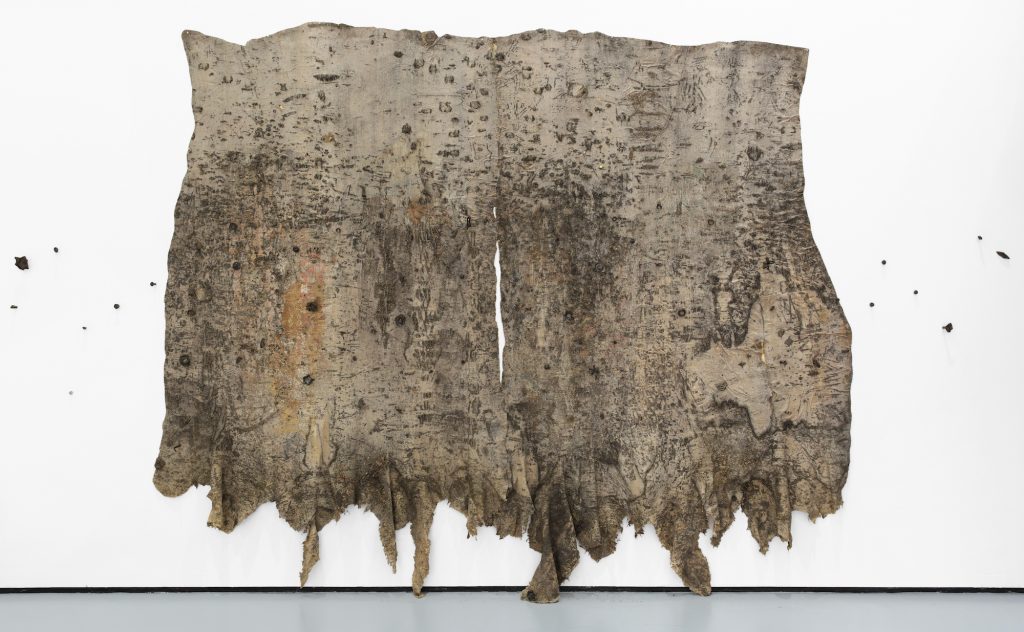

Large rubber molds of ficus trees by Los Angeles artist Eddie Aparicio (b. 1990) are stretched out across a wall and suspended from the ceiling. These works reference traditional and artistic practices of indigenous cultures as well as deforestation. The wall piece is unadorned and bears the rugged marks of the massive tree trunk from which this rubber mold was taken. Tapered at the top and heavier at the bottom, this piece, and others by Aparicio, document the impact of urbanization on nature in predominantly Central American neighborhoods around Los Angeles.

Los Angeles artist, Carolina Caycedo (b. 1978) took over a large space to draw a family tree on the walls and lay out a small altar to honor environmental activists who were either killed or threatened while fighting for their cause. Drawn directly onto the wall, Genealogy of a Struggle is a sprawling memorial tied to the artist’s commitment to the environment, activism, and the right to be heard.

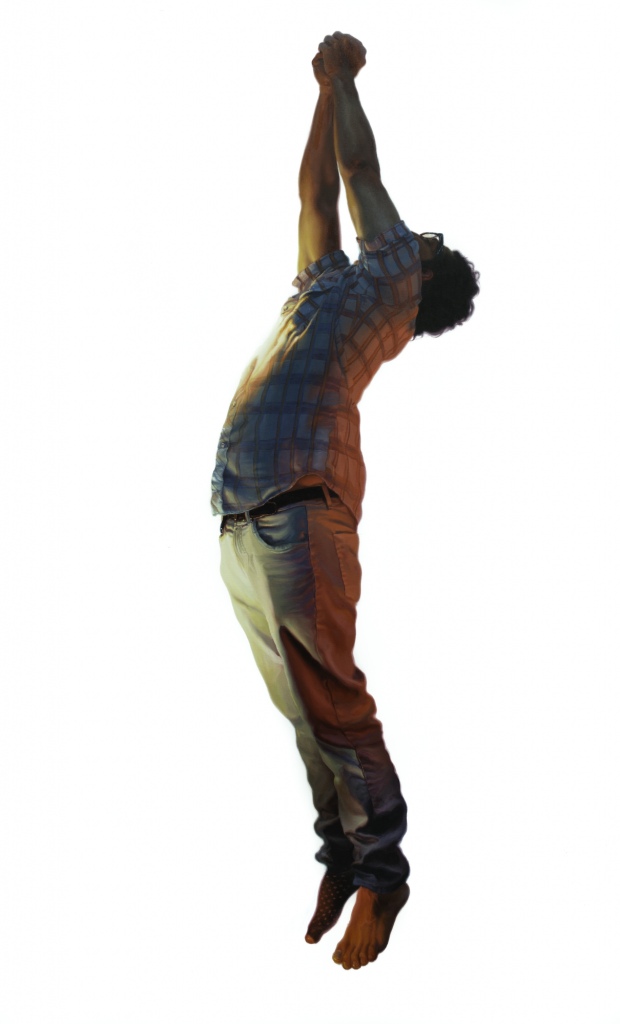

One of the last and most striking works seen during my visit to El Museo was The Strangest Fruit by Texan artist Vincent Valdez (b. 1977). From a distance, these paintings depicting larger-than-life and torqued bodies against a pristine white background instantly reminded me of the playful drawings of Robert Longo from his 1980s series Men in the Cities. The similarities between these two series is purely formal, though, because embedded within Valdez’s paintings is a dark history pertaining to Mexican and Mexican-American lynchings that took place in the Southwest of the United States from the late 19th century to 1930. The artist is re-telling unknown stories with paintings based on models who were asked to pose as the victims of this gory history.

The history of the Unites States remains incomplete and full of blindspots, as there remain too many forgotten or untold stories of inhuman acts of violence. Some of us may be fine, but many are not and it may be a source of comfort to think that we dream together. It is imperative that institutions like the Asia Society Museum and El Museo del Barrio continue to probe into these uncomfortable spaces.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!