10 UNESCO World Heritage Sites to Visit in France During the Olympics

Visitors to the Olympics will not only be able to enjoy the sports while supporting their favorite countries and athletes. France offers an unusual...

Ledys Chemin 29 July 2024

With mesmerizing colors dancing in the night sky, witnessing an aurora must feel like being inside of a painting. What are the northern lights and how are they captured in art?

Auroras are meteorological phenomena visible as colorful night spectacles. They can be seen near the poles of the hemispheres. In the Northern Hemisphere, they are called “aurora borealis,” and in the Southern, “aurora australis.” Today, we’ll focus on the first, commonly known as the “northern lights,” and see how they inspired art.

Bror Lindh, Northern Lights, 1900, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Northern lights are caused by a direct hit of particle activity from the sun. During a solar storm, the sun’s surface emits clouds of electrically charged particles. Some of these particles get captured in the Earth’s magnetic field and accelerate towards the North and South Pole. The particles collide with atoms and molecules from our planet’s atmosphere and heat them up, which manifest in wavy light patterns.

August Matthias Hagen, Northern Lights, 1835, Tartu Art Museum, Tartu, Estonia.

When heated, the different gases in our atmosphere emit a different color. Oxygen creates green, and the second primary gas, nitrogen, creates purple, blue, or pink. These can also mix with each other. The colors we see are also dependent on the particle energy load, wavelengths, and altitude. Science proves that this phenomenon occurs on other planets too, and the Hubble telescope was able to capture them on Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Gudmund Stenersen, Fra Svolvær, before 1934, Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum, Tromsø, Norway.

The northern lights can not only be seen but also heard. Recordings from the Finnish Fyskar village prove that a small percentage of auroras emit sound. The crackling and whooshing is caused by a temperature inversion and electrical discharge in the magnetic field.

Francois Biard, Magdalena Bay, ca. 1847, private collection. Photograph by bongo vongo via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The earliest known depiction of the northern lights is traced to the Cro-Magnon cave paintings in Cantabria, dated to 30,000 BCE. The term “aurora borealis” was coined in 1619 by Galileo and refers to the Greco-Roman goddess of the dawn Aurora and god of the cold north wind, Boreas. Similarly, the aurora australis is derived from the name of the god of the south wind, Auster.

Cave paintings, 30 000 BCE, Cave of Altamira, Spain. Oboz.ua.

Early depictions of northern lights in art are rare, but it’s possible the occurrence of this atmospheric event was depicted through metaphors. In written records, these night lights are often described as spirits associated with fire: the red dragon Shilong in Chinese Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhai jing), ancient Finnish folk “fox fires,” or (in the case of aurora australis), evil fire spirit kootche in Diyari aboriginal folklore.

In the 1570 engraving from the Crawford Library in Scotland, the northern lights are, quite literally, a fire of candles in the sky.

Copy of engraving depicting Aurora Borealis, 1570, Crawford Library, Edinburgh, UK.

In Old Norse mythology, northern lights were said to be a rainbow bridge between Earth and the realm of gods. Some of the Sami people, indigenous to large parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia’s Kola Peninsula, believed the northern lights were the blood of the dead warriors injured in the sky. In the Sami tradition, whistling during northern lights highly disrespects the ancestor warriors, who will “spirit away” the whistler.

The first big scientific hypotheses on the occurrence of northern lights were formed in the 18th century. In 1716, Sir Edmund Halley correctly theorized that auroras are caused by particles being affected by the magnetic field. Today we know that many of these theories were already introduced by the ancient Greeks. In 1778, Benjamin Franklin claimed that auroras are caused by a concentration of electrical charge intensified by snow and moisture in the polar regions. In 1902, a Norwegian scientist, Kristian Birkeland, laid the foundation for modern understanding of the phenomenon and the solar flare theory.

Along with scientific discoveries and expeditions came illustrations, such as Etienne Trouvelot’s colored plates with aurora borealis or the frontispiece to Nobel laureate Fridtjof Nansen’s arctic exploration accounts.

While auroras are a naturally occurring phenomenon, their sightings are hard to schedule. Scientists can usually predict them with a 30-minute warning by speculating on the global geomagnetic activity index readings or monitoring solar wind density. Predictions can also be made through solar activity cycle observation.

William Holmberg, Revontulet, 1849, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Most of the paintings in this article were created by artists from Northern Europe, mainly Scandinavia. In this region, auroras can be spotted in secluded locations between the months of September and October. The northern lights frequently appear in the art of Peder Balke (1804–1887), a Norwegian painter of Romantic naturalism.

Another painter of auroras is Harald Moltke (1871–1960), a Danish artist mainly known for his illustrations of Greenland expeditions. His Nordlys series were painted during his observations in Iceland and Lapland, each titled with a date and time of sighting.

The most famous artwork depicting the northern lights is Aurora Borealis by Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900). This outstanding piece is based on two sketches provided by Church’s friend, an Arctic explorer Isaac Hayes. It presents a ship passing through a dark Arctic environment. The green, red, and blue lights on the sky can be interpreted as a beacon of hope.

Frederic Edwin Church, Aurora Borealis, 1865, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Another notable artist who depicted northern lights is Anna Boberg (1864–1935). Although born in Sweden, most of her paintings feature the landscapes and people of northern Norway’s Lofoten area. Her husband, who was an architect, built her a small house on the Svolvær Fyrön island. When he retired from his career, they traveled along Sweden, sketching and documenting Nordic cultural heritage.

Anna Boberg, Northern Lights. Study from North Norway, after 1900, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden.

Anna Boberg, Northern Lights. Study from North Norway, after 1900, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden.

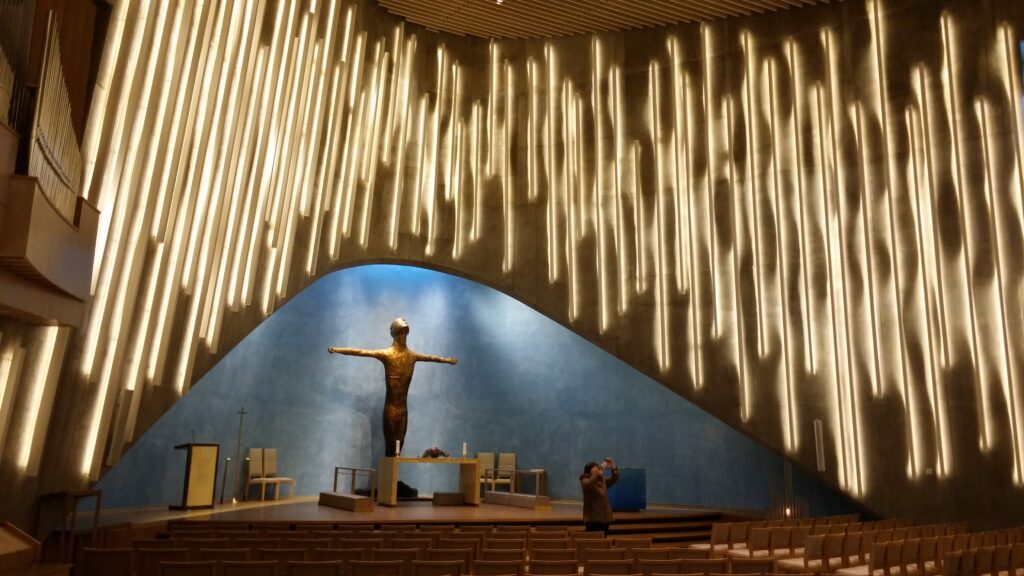

Such mesmerizing sights can result in an almost religious experience. The northern lights have a cathedral built in their honour—the Northern Lights Cathedral, located in Alta, Norway. Just 250 miles out of the Arctic Circle, the circular building was consecrated in 2013 and hosts aurora-inspired art by Peter Brandes. It is among one of the most popular travel spots for aurora-seekers.

Peter Brandes, Altarpiece for the Northern Lights Cathedral, Alta, Norway. Photograph by

We have a strong feeling we inspired you to make your own trip to see the northern lights in person, not just through art. The most useful guide on how to see the northern lights can be found on the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center‘s website. We recommend reviewing it in preparation for your journey towards the magnetic pole. Perhaps you’ll make your own painting too!

Carl Svantje Hallbeck, , 1856, from Svenska Familj-Journalen. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!