5 Ultracontemporary Artists Redefining the Korean Art Landscape

The dynamic South Korean art scene is quickly becoming one of the most prominent globally, blending rich traditions with cutting-edge innovation. And...

Carlotta Mazzoli 13 January 2025

The Picasso of the North, as he was known throughout Europe; Copper Thunderbird, as he was known in the Anishinaabe region of Canada. Whatever you’d like to call him, Norval Morrisseau’s work transcended time and opened the door for contemporary Indigenous artists throughout Canada. Ultimately he became the grandfather of Indigenous contemporary art.

I’m the grandfather. Instead of being Grandma Moses, I suppose I’m Grandfather Morrisseau or something like that. And they tell me that I have opened these doors for them.

Art Canada Institute

He never wanted to do anything but hear stories and draw. From a young age, Norval Morrisseau, born in 1931 and raised around Ontario, Canada, was different. Like most Indigenous children at the time in Canada, Morrisseau was forced to attend a residential school. Furthermore, he and his people were prohibited from practicing their traditional beliefs.

Unlike most children, Morrisseau only wanted to make art. He never received any formal art training and, as tradition would have it, would spend time living with his grandparents on a reserve. It was there that he learned the traditional Indigenous stories and cultural traditions of his people from his grandfather, Moses Potan Nanakonagos, a shaman who was trained in the local spiritual tradition.

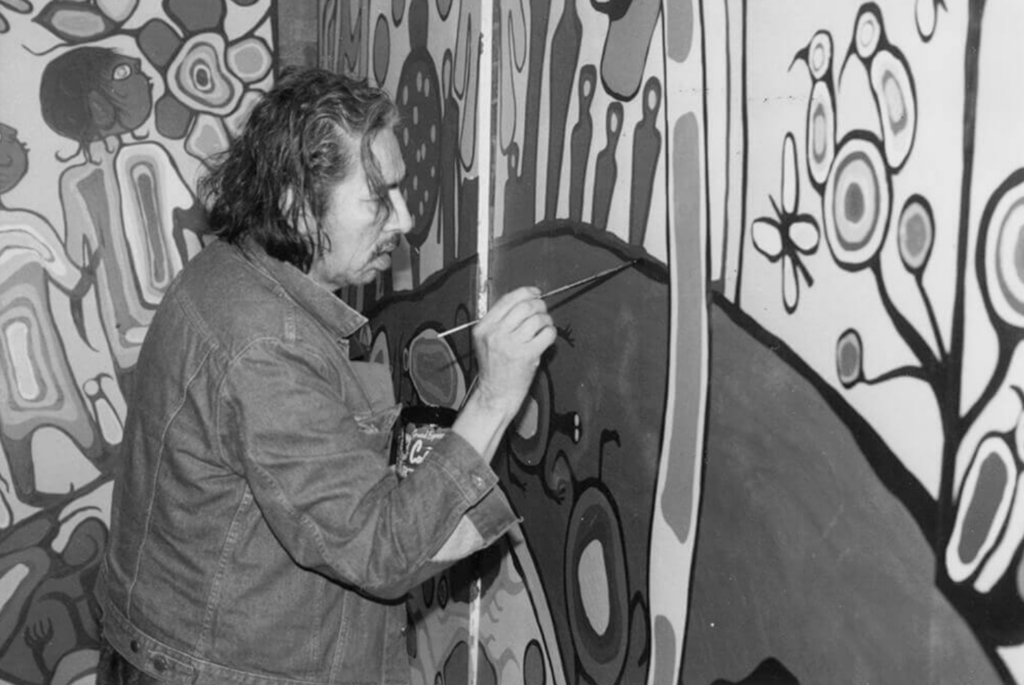

Norval Morrisseau, Artist and Shaman between Two Worlds, 1980, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

According to curator Greg Hill, “Morrisseau was not like other children in his community. The young artist preferred to spend his time in the company of elders listening and learning, or completely alone, drawing.” At the age of ten, having attended both public and residential schools, where he was forced to forget the traditions he loved, Morrisseau dropped out of school with nothing but stories and a love of art.

His works are in a category unto themselves. They look both as if they could be found inside a cave painted 20,000 years ago and hang on the wall of a contemporary art gallery. The gestural heavy black outlines combined with the vibrant color palettes bring life to the pieces. It is almost as if you can see the sacred bear dancing on the canvas.

The journey to becoming the greatest Indigenous artist in North America was anything but smooth. After years of working odds-and-ends jobs and painting on the side, Morrisseau was finally convinced to take up painting full-time around 1958 by a couple who liked his works. They provided him with high-quality art materials and told him to call himself a professional artist, in the “Western” sense of the phrase. However, it would take some time before his work was taken seriously.

He was the definition of a self-taught artist, a student of his craft. He was inspired by the murals of Diego Rivera and the works of Salvador Dali and Henri Matisse. Also he was interested in local petroglyphs and birchbark scroll images. These influences all combined to create his unique style.

At first, the elders weren’t fond of Morrisseau sharing their traditional stories on the canvas for the masses. Galleries and museums specifically didn’t know how to categorize or place his works with his contemporary art peers. The word that kept coming up was ‘primitivism’, a word for popular, often European artists that could be used for inspiration. However, for an artist, specifically Indigenous artists who “don’t belong”, this was a slight.

Picasso was, in fact, inspired by and perhaps even obsessed with, primitivism after being introduced to African folk art by a friend and fellow artist, Henri Matisse. The only thing that curators could keep coming back to was primitivism. How could this artist who wasn’t properly trained nor attended school make art that wasn’t “primitive”?

It didn’t help that Morrisseau had a problem that he couldn’t shake. Since he was a teenager, he had problems with alcohol. He even spent time on the streets for a short period as well as a six month stint in jail, in which he was fortunate enough to have another jail cell set up as his art studio. While he continuously bounce back, the press only seemed to care about his downfall, further hurting his chances of international success.

I am tired of hearing about Norval the drunkard, Norval with the hangover, Norval in jail, Norval torn apart by his allegiance both to Christianity and to the old Indian ways.… They speak about this tortured man, Norval Morrisseau—I’m not tortured. I’ve had a marvelous time. When I was drinking. Now that I’m not drinking. I’ve had a marvelous time in my life.

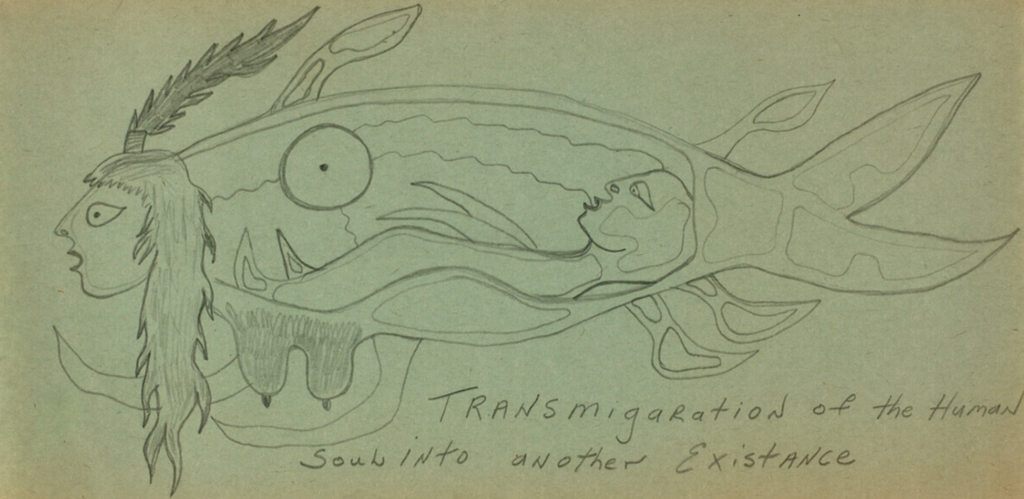

Artwork by Morrisseau completed in jail: Norval Morrisseau, Transmigration of the Human Soul into Another Existence, 1972–73, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

Through all of this, Morrisseau continued to paint. He dedicated all of his works during his life to being saved at a young age thanks to a healing shaman. It was at this time that he ended up being renamed “Copper Thunderbird”, in his words, “a very powerful new name; and it cured me.” He would sign all of his works with this new name in Ojibwe script moving forward, representing his own vision of the legends and myths of his people.

Similar to other Indigenous artists like Fritz Scholder, Morrisseau struggled with this new vision and interpretation of the stories he knew as a child. He wanted to respect and paint what he knew, meanwhile he didn’t want to be known simply as an “Indian” artist. He was much more than that. Gradually, his works evolved into a more stylized version of previous Indigenous art. Morrisseau tried his best to continue to spread the word and share the wisdom of a people who had faded out, while also living beyond this culture without completely leaving his morals behind.

Film still of Norval Morrisseau painting alongside his daughter from the National Film Board documentary The Paradox of Norval Morrisseau, 1974.

In the early 1960s, with a family to feed and an urge to paint, Morrisseau believed he was one of the best painters in Canada. Finally, his time to take his work mainstream would come when he met gallery owner Jack Pollock.

Pollock had heard murmurings of this Indigenous artist who was working on birchbark with watercolors, but he didn’t want some tourist-type artwork for his gallery. Once he met Morrisseau, Pollock didn’t believe that this man, with no training and little to no resources, living in the bush north of Toronto, had created these magnificent works of art. Almost overnight, with his first exhibition taking place in Toronto, Norval Morrisseau became a celebrated artist. All of his works sold, marking the first time an Indigenous artist had shown work in a contemporary art gallery in Canada.

As Morrisseau’s popularity grew, so did the criticism. Now showing works all across Canada, into the northeastern United States, and with his first European exhibit to open in 1969, critics, gallerists, and art fans didn’t know what to make of his work. Was it modern? How could it be contemporary if it was from an Indigenous self-taught artist from Canada? The word that kept coming up over and over again was still primitive. Morrisseau’s work was anything but primitive.

It wasn’t until the 1969 exhibition in the south of France, where his works were exhibited in areas that hailed artists like Pablo Picasso and Marc Chagall, that Morrisseau’s work was finally taken seriously. Posters for the exhibit marketed the artist as “The Picasso of the North,” leading to some long-deserved recognition as an artist and establishing his international reputation.

For the years that followed, Norval Morrisseau continued to paint and confound galleries and museums across Canada. Furthermore, it was obvious that a new generation of artists was inspired and influenced by Morrisseau. In the 1980s, his contemporary work was being purchased, for the first time ever for an Indigenous artist, by modern art museums. In 1984, a show called Norval Morrisseau and the Emergence of the Image Makers took place in Ontario.

Norval Morrisseau in front of his painting Androgyny, 1983, at the opening of his solo exhibition Norval Morrisseau—Shaman Artist at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2006

As the years passed, Morrisseau continued to struggle with alcoholism, tuberculosis, and Parkinson’s disease. He wasn’t making as much of his colorful, flowing, and eye-popping artwork anymore. By the early 2000’s, some contemporary artists had never seen his work in museum collections, often they were not on display. His career culminated in 2006 when the National Gallery of Canada mounted an retrospective of Morrisseau’s career. It was the first time that a contemporary Indigenous artist had an exhibit there. Thankfully, it also renewed interest in Morrisseau’s art, with a cemented understanding of his work within the history of Canadian art.

The following year, Norval Morrisseau, Copper Thunderbird, “The Picasso of the North,” died due to complications his Parkinson’s. Now, he is forever known as Mishomis, the grandfather of contemporary Indigenous art.

Norval Morrisseau Life & Work by Carmen Robertson, Art Canada Institute

The Paradox of Norval Morisseau, 1974 documentary directed by Duke Redbird for National Film Board of Canada

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!