5 Famous Artists Who Were Migrants and Other Stories

As long as there have been artists, there have been migrant artists. Like anyone else, they’ve left their homeland and traveled abroad for many...

Catriona Miller 18 December 2024

Although he only lived 34 years, it could seem that Yves Klein lived more than one life. This French artist initially devoted himself to the discipline of judo, until he ruled out that art was his real love and aim in life. He is especially known for his blue works. However, he actually realized many other incredible masterpieces besides the blue ones. Let’s discover some of them.

Yves Klein was born in 1928 in Nice, France. His parents were both painters and because of their work, during his childhood, Yves had the possibility to live both in Nice and Paris. Moreover, he could experience art every day and gradually started making it himself in his late adolescence. He initially had completely devoted his life to judo, his primary occupation until the beginning of the 1950s.

From 1954 on, he decided to be a full-time artist, progressively but definitively abandoning his career as a judoka. Between 1948 and 1953, he traveled a lot, visiting many countries in Europe such as Italy, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain, as well as Japan. These years will later have a particular influence on him and his art.

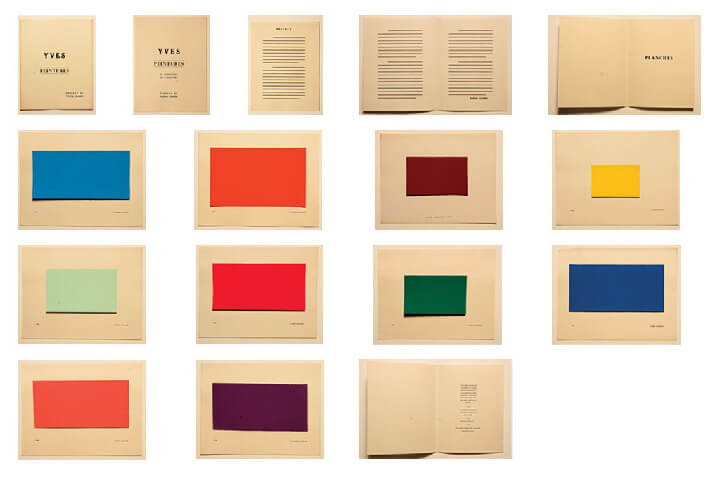

In 1954, Yves Klein published two books, Yves Peintures and Haguenault Peintures. They are full of monochromes, a real hallmark of the artist in the following years. The preface, ending with the signature of the poet and Klein’s friend, Claude Pascal, actually presents black lines in different lengths instead of words. On the other hand, the “representations” of the monochromes are, in fact, real artworks. They are rectangular pieces of paper with the indication of their dimensions (in millimeters), linked to specific cities he had lived in.

We can see here two of the characteristics of Klein’s art: the immateriality of the surface and the love for the monochrome. This latter point, almost an obsession, was alimented by his strong will of “setting free the color from the jail of the line” and showing the world something recalling the absolute and the infinity.

Not Just Blue Masterpieces by Yves Klein: Yves Klein, Yves Peintures, 1954, copy from the original. The Sartler.

The search for the absolute and infinity could not separate from “immateriality” and “invisible”. The first step to express this essence of art was exclusively adopting ultramarine blue.

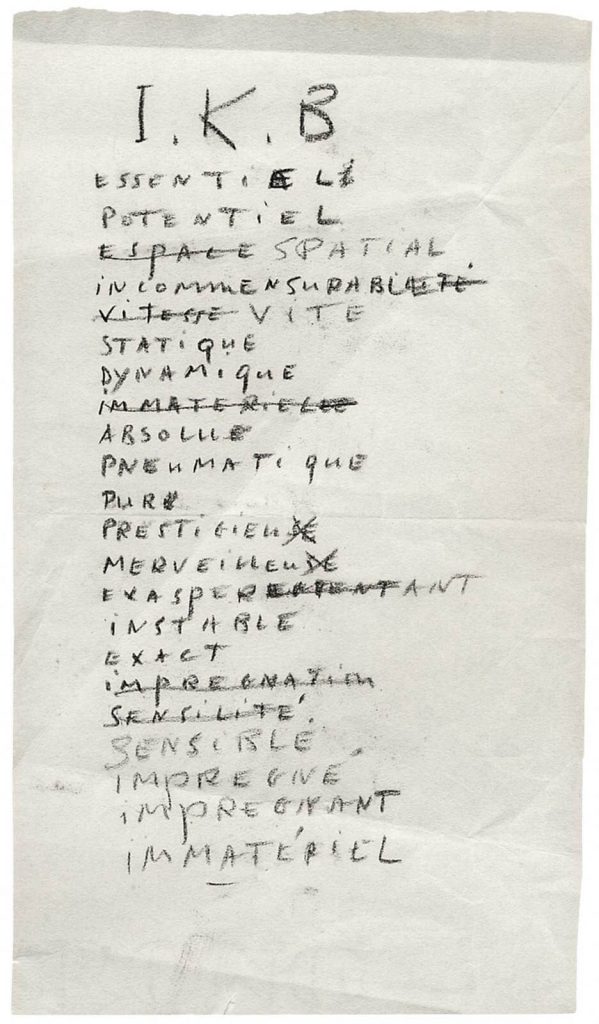

In 1956, in collaboration with Edouard Adam, a paint supplier working in Montparnasse, Paris, he projected and materially created a specific nuance of blue: the International Klein Blue, or IKB. It included a synthetic resin that is able to maintain the extremely pure intensity of the color. At the time, it was a French pharmaceutical company, the Rhône-Poulenc, which developed this resin with the name Rhodopas.

In 1960, Yves Klein registered the paint formula at the Institut national de la propriété industrielle (INPI), an institution of the French government. He had begun a sort of revolution both in his artistic life and globally.

Not Just Blue Masterpieces by Yves Klein: Yves Klein, Note on I.K.B., 1959. Artist’s website.

Klein’s revolution did not stop there. He continued to try and go beyond a standard definition of art. Therefore, in 1958, in Paris, he made a personal exposition called La spécialisation de la sensibilité à l’état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée (the specialization of sensibility in the raw material state into stabilized pictorial sensibility), which was however soon called Le vide or The void.

At the entrance, the windows were painted in Klein’s signature blue. On the day of the presentation, Klein offered a blue cocktail to his audience. Inside, he exposed an empty room, with walls and windows painted in white, declared as “filled with his pictorial sensibility”. In other words, he wanted people to perceive the void and the invisible as fully finished artwork. The exposition was so successful that closure was postponed for a week and a documentary later explained it in detail. The journals of the time reported his visionary ideas.

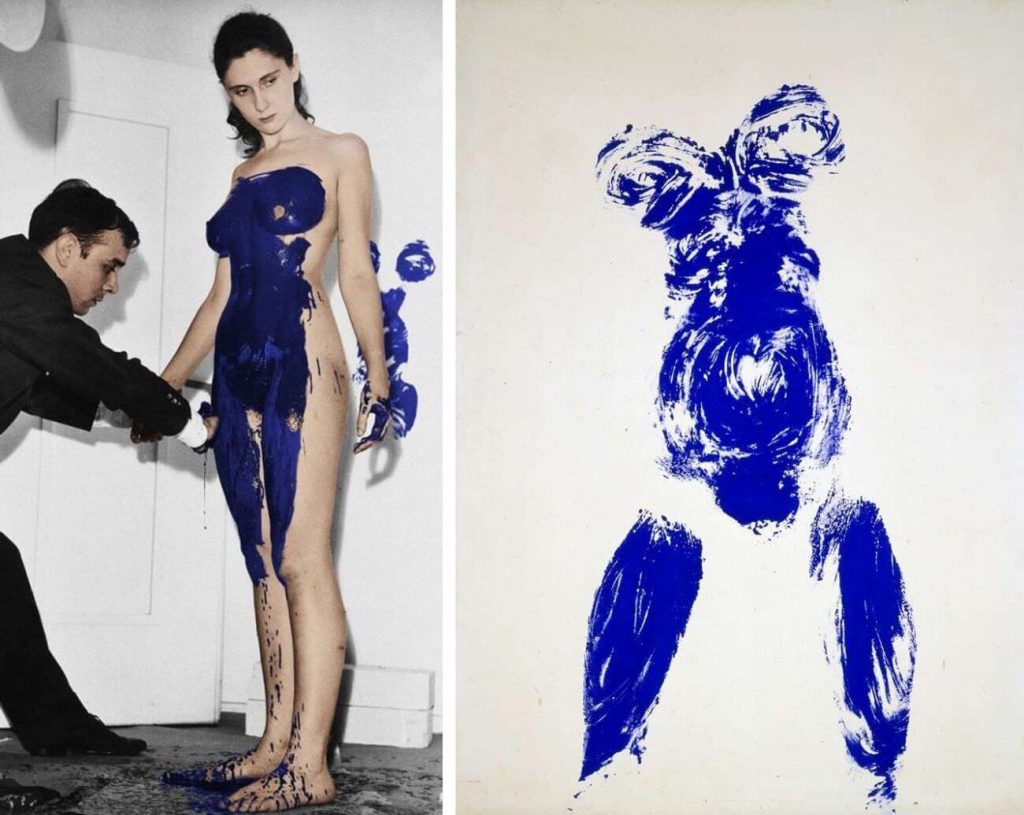

Then, particularly after 1960, Klein moved even further and began to experiment in the field of performance art. On March 9th of that year, he chose an audience to be attending his performance at the International Gallery of Contemporary Art in Paris. With a monotone symphony in the background, composed by Klein himself, three naked models came on the stage and were painted in blue paint. Klein then gave them directives to imprint the canvas with their bodies. The title of this performance was Anthropométries de l’époque bleue or Anthropometries of the Blue Age. They shed completely new light on the relationship between the artist, his models, his brushes, and his final works.

Not Just Blue Masterpieces by Yves Klein: Yves Klein, Anthropometries de l’époque bleue, 1958. Blog Wipplay.

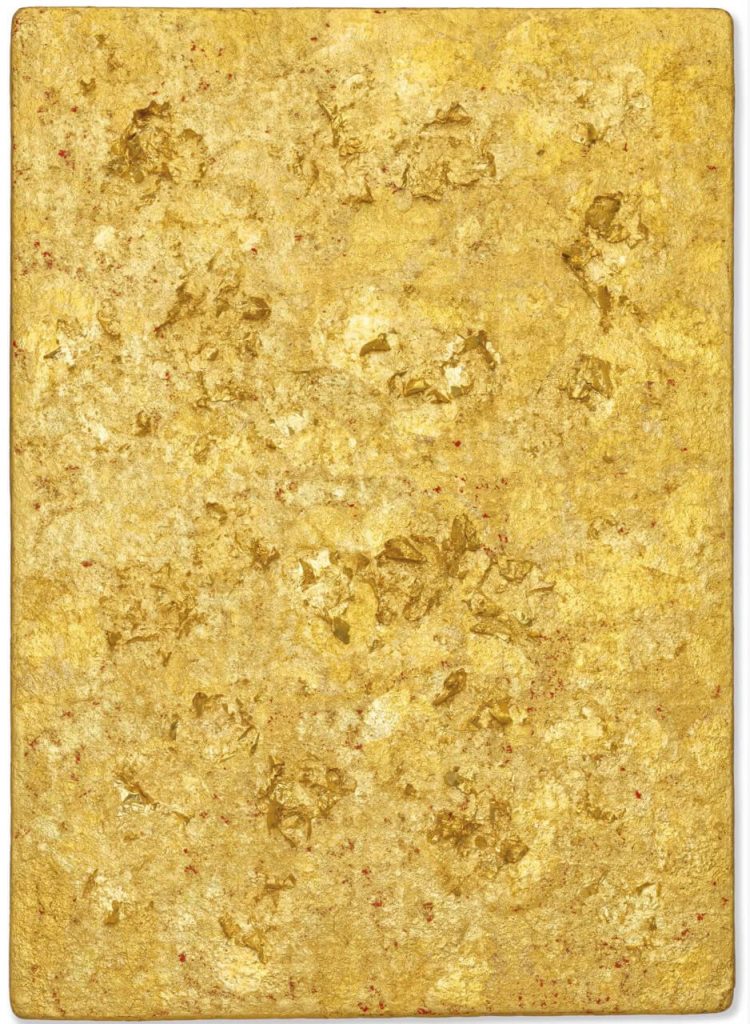

A natural evolution of the concept of immateriality and infinity was the realization of the Monogolds, artworks in which gold was the absolute main character. It was not only precious but also very symbolic. First of all, it probably reminded him of both an ancient chivalric age that he used to love since he was a child, and Buddhist and Taoist temples he used to see while studying judo in Japan. Moreover, it was revealed as an ideal material to express his artistic obsession: gold could maintain its vitality, color, and intensity without problems of fixatives. Finally, its preciousness could also suggest how important was the concept it represented.

Not Just Blue Masterpieces by Yves Klein: Yves Klein, Monogold sans titre, 1961. Christie’s.

Next to performance art and his interest in gold, from 1960 onward, Klein also started to produce artworks created with the support of weather and natural elements. For example, he fixed a freshly painted piece of paper on his car and he allowed wind, rain, and other conditions to conclude the artwork. He also dipped artworks in rivers. These works were the Cosmogonies, from the greek Kòsmos: world, universe. Art was the perceivable form of nature and its power and infiniteness. According to Klein’s ideas, beauty is already existing in the world, existing as an invisible force. Therefore, the artist has the unique duty of looking for it everywhere it is.

Rotraut Klein-Moquay, Yves Klein réalisant une Cosmogonie sur les berges du Loup, 1960. Artist’s website.

From this conclusive concept, at the end of his life (1961–1962), Yves Klein even experimented with extreme, and partly dangerous, forms of art. Peintures de Feu and Peintures de Feu couleur, or fire paintings and fire color paintings, were a series of artworks realized at the Centre d’essai de Gaz de France, next to Paris. The flames were the painters on large sheets of paper or cardboard, which could carry the marks of sculptures or other objects. It was certainly a spectacular way to conclude his incredible career, always centered on the tentative to let the artist’s entire life be a stunning artwork.

Not Just Blue Masterpieces by Yves Klein: Yves Klein, Peinture de Feu sans titre, 1961. Artist’s website.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!