Emil Carlsen was, for roughly the first forty years of his life, poor and relatively unknown. After all, he rejected the growing appeal of florid color and captured, fleeting light that predominated modern Impressionist taste. Instead, he adapted it, adding principles from his native Denmark. From this practice arose an American Impressionist with a uniquely Danish style – and ultimately unlike any other.

Raised in Copenhagen, Denmark, Emil got his first exposure to art through his family. His cousin Viggo Johansen was a member of the Skagen painters, who emulated French Impressionists, and his mother received painting lessons from I.L. Jensen, who was known for his flower still-lives.

After attending the Royal Academy of Art and serving a brief stint in the army, Carlsen came to New York to work as an architect. Eventually he began work in the studio of Lauritz Bernhard Holst, who once sold a sketch of Carlsen’s under his own name. However, when Holst died, it was Carlsen who inherited the studio.

He left a job teaching drawing at the Art Institute of Chicago to travel Europe studying. But it wouldn’t be until his three year period in Paris from 1884 to 1887 that he would adopt the colors of the Impressionist Palette.

Upon returning, Carlsen spent a few years in San Francisco serving as the head of the city’s Art Association. His return to New York marked the beginning of his permanent residence on the East Coast, where he fell in with William Merritt Chase, Childe Hassam, and Julian Alden Weir, amongst others. These American Impressionists helped shape Carlsen’s work into what it remains today.

“Old Carlsen,” though he spent most of his career as a painter in America, was a fundamentally Danish artist. His balance between the calm and the emotional was similar to his contemporaries at the Skagen school, though more reserved, as was Danish custom. However, he was always compared to the American Impressionists, with similarities between his style and that of American genre painting present as well.

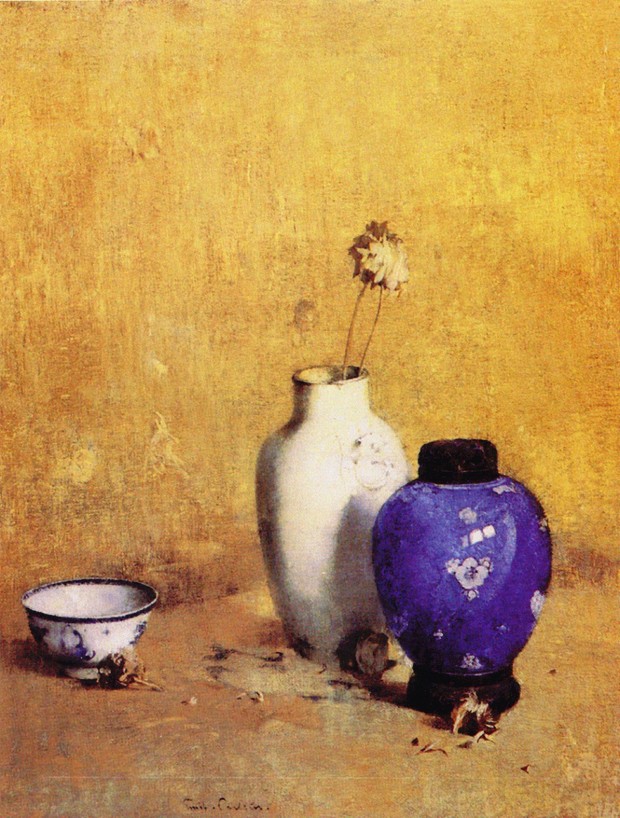

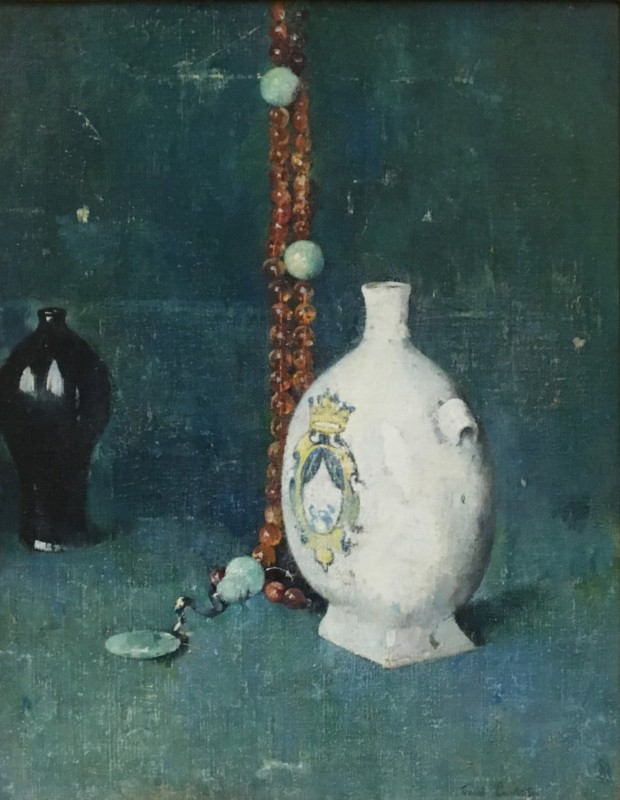

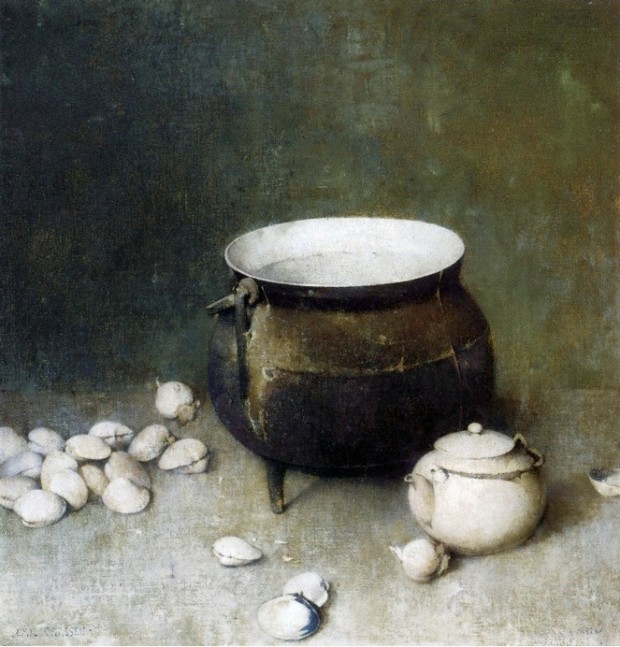

He took a particular interest in still-lives – not just in his dedication to a “veiled” appearance of light in the brushwork, but in the composition of the objects arranged, which maintained a silent harmony. Carlsen didn’t believe life needed to be depicted in every painting; instead, his still lives suggest the absence of life – not death, per se, but the feeling that there was once life present, or that there will be.

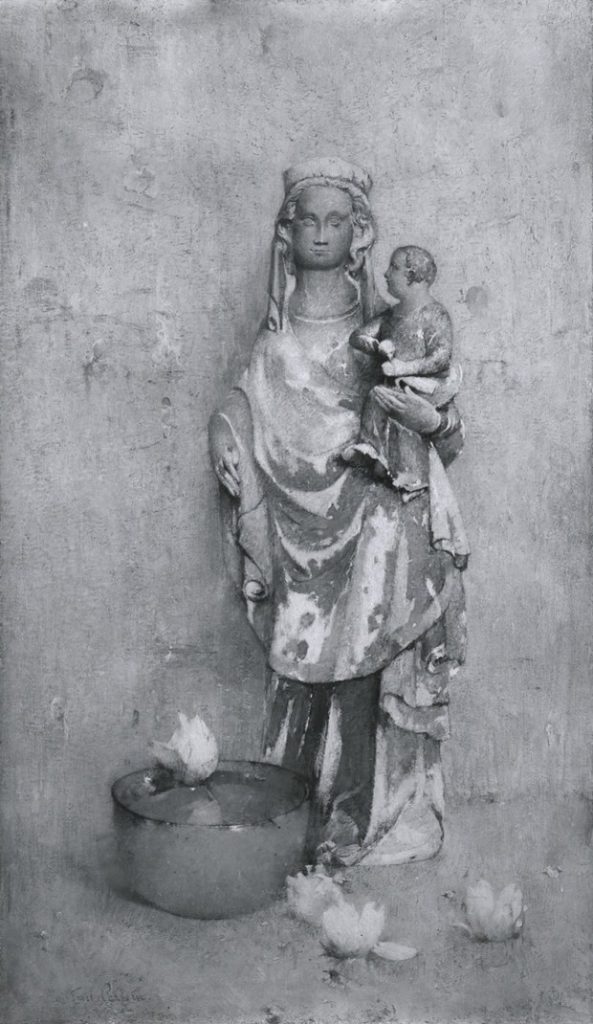

He was particularly fond of depicting porcelain, where his approach to the use of white is most plainly apparent. Carlsen was known to mix some amount into every pigment he applied. As a result, his palette remained light, yet reserved. His grisailles – compositions done entirely in grey – look almost like early photographs of statues. With his porcelains, his ability to manipulate light on a white surface with the subtlety of reality became highly admired.

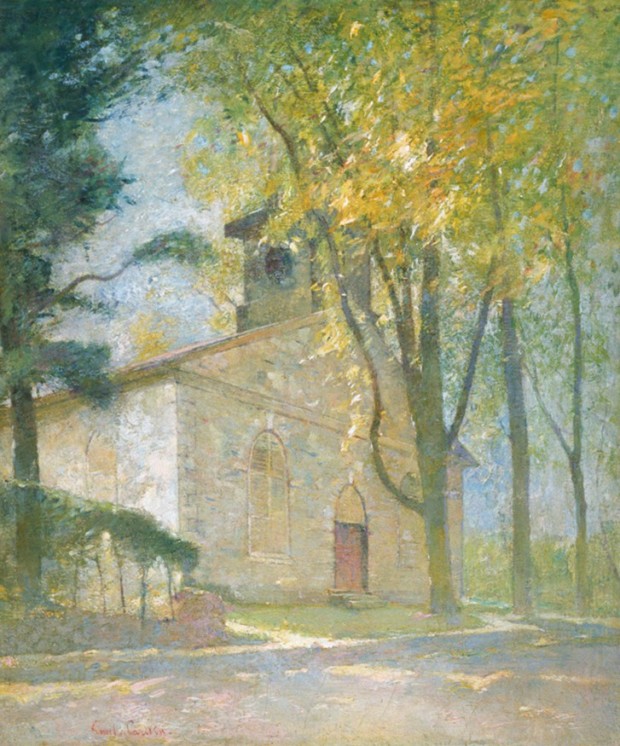

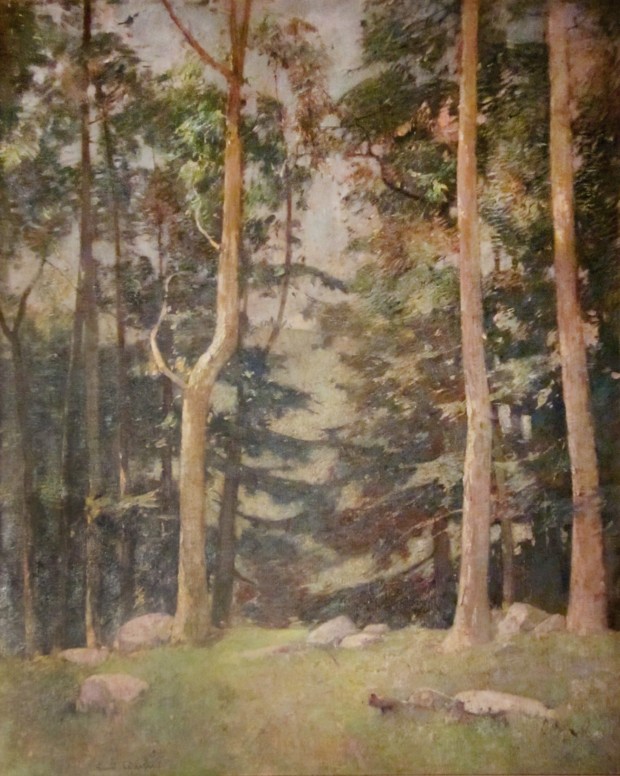

Carlsen’s landscapes, too, adopted his light-infused colors and shapes. He frequently employed large areas of positive space composed of sky, land, sea, or simply colorful background. Grey days when a mist hung in the air seemed his favorite, and the appearance of a fog (or smudge on the lens, perhaps, were he a photographer) lingers in most of his landscapes.

Much like photographs, Carlsen’s paintings contain a solid stillness. Yet, as per the Impressionists, he captures light in a fleeting sense that blurs the composition. Thus his landscapes appear as though a photographer accidentally hit the camera; there is motion amidst the rigidity.

Overall, Emil Carlsen was considered by his contemporaries and is still by historians to be one of the finest painters of his time. His fellow artists claimed his work captured the essence of the man himself, someone who lived life “simple and true,” as the collector August Bontoux put it. His death in 1932 at the age of the 83 left the art world with a wealth of uniquely honest and organic paintings that embodied not only a lifetime of work but the life that conceived it.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B0006R9OO0″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/512d30jEcwL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”133″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”B00P4P2GBC” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/51pBI015kDL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”100″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”142″ identifier=”B0026NZMC0″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/51pXwFsTjEL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”160″]