The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

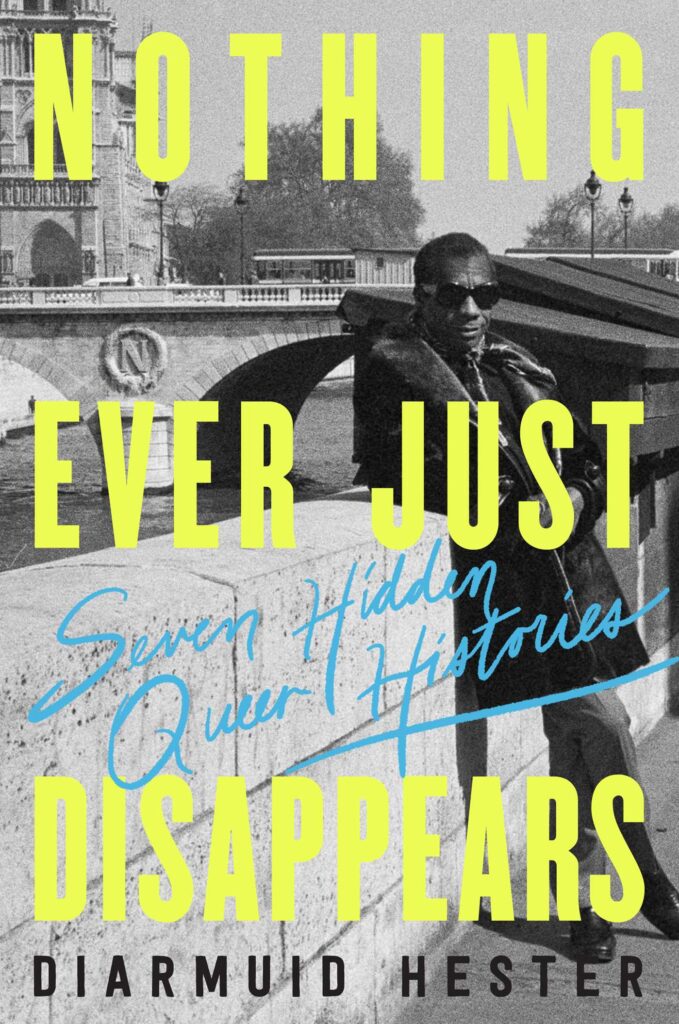

How does the place where art was created impact the work itself? And, in turn, can art influence how we view those very places? Diarmuid Hester considers this and much more in his biography Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories (Pegasus Books, 2024).

These questions of the relationship between an artist and the places they lived and worked are investigated through a dynamic queer lens. Indeed, queerness is integral rather than incidental, something that is inextricable from the artists’ respective journeys.

Front view of Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, 199?, by Howard Sooley. Courtesy of the publisher.

Each chapter of Nothing Ever Just Disappears is devoted to different historical figures and the places they are tied to, from the well-known to the obscure. The narrative is a blend of history, memoir, and often wistful imaginings as Hester journeys himself to the very places he is writing about.

Sights, sounds, and smells are vividly described. You are always immersed, regardless of how familiar you may be with each place.

For instance, the excitement and possibility of the bisexual Josephine Baker’s Paris, and the German occupation encroaching on Claude Cahun’s Jersey—such experiences all feel within touching distance with Hester as our guide.

Claude Cahun, Self-portrait, c. 1928. Courtesy of the Jersey Heritage Collections and the publisher.

Furthermore, there’s a particularly arresting opening when Hester introduces a chapter on queer suffragettes, where you’re swept up into the scene of Vera Holme, chauffeur to Emmeline Pankhurst, as she tears through Edwardian London in her car. A trailblazer in every sense of the word!

Hester’s work is well-researched and thoughtful. He doesn’t depict such historically significant queer people as figureheads to simply be venerated for what they represent.

Instead, we’re shown complex, well-rounded portraits, with all the messiness and contradictions that come from being human.

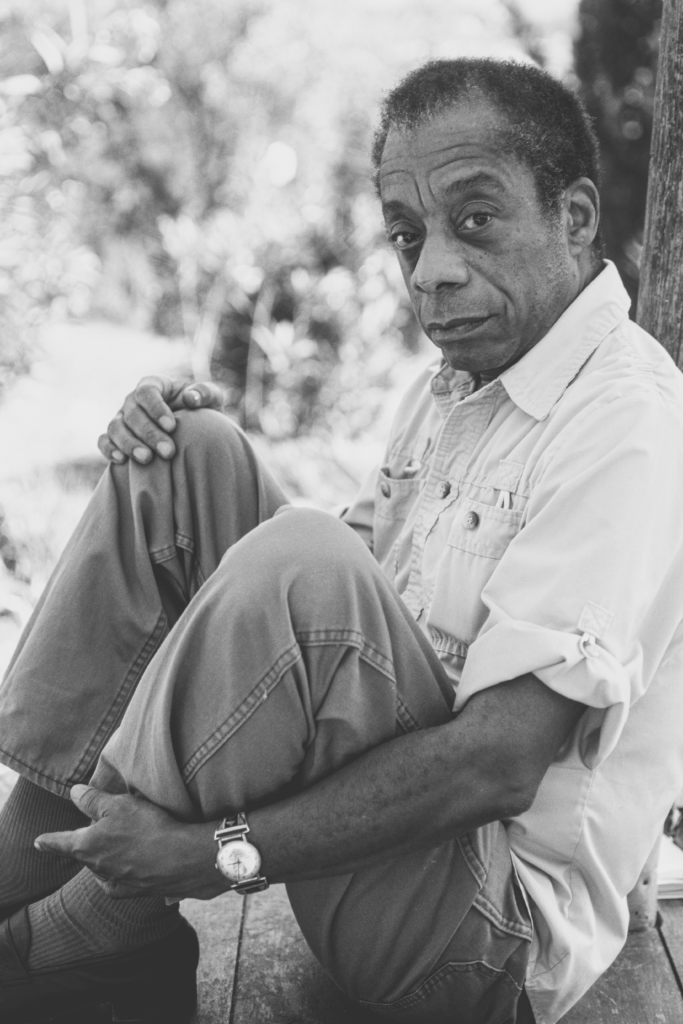

For example, author James Baldwin is given both a compassionate and fair evaluation. The painful impact of his religious upbringing on his work and perspective is fully recognized. Additionally, his regressive views on the flourishing gay and lesbian movement he witnessed are acknowledged in equal measure.

James Baldwin in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1985. Photo by Ulf Anderson. Courtesy of the publisher.

There’s a consistent personal touch throughout Nothing Ever Just Disappears. Hester often brings his own Irish Catholic background into the discussion of ‘place responsiveness’—how places impact us, especially LGBTQ+ people. We are encouraged to think deeply about spaces, places, and why they matter.

In particular, something prevalent both in history and today is the migration ‘coming out’ narrative: moving from small town, country life to the comparatively liberal city.

Through Hester’s honest, engaging narration, I found myself reflecting on my own lesbian identity, and why that particular coming out narrative resonates with me, especially when portrayed in fiction. I wondered whether it too could be turned on its head—queered, even.

The stereotype of rural locations enforcing heterosexist conformity could be hiding how, for some queer people, such places may spell liberation, too.

However, there are occasional instances where such thoughtfulness seems to slip away in favor of the author’s own judgements. Much care is taken to describe the challenging environment of E. M. Forster’s Cambridge, and how it contributed to his reticence in expressing overt homosexuality.

Written in 1913 and dedicated ‘to a happy year,’ Forster’s seminal gay novel, Maurice, would not be published until 1971. In Nothing Ever Just Disappears, he is bluntly categorized as ‘conventional’ for not publishing such groundbreaking queer literature in his lifetime.

Personally, I would say that to live in such a time and place, simply writing down declarations of gay love is a revolutionary act in and of itself.

There’s a thread of loss that runs through Nothing Ever Just Disappears.

Poignant moments occur whenever Hester visits a place once monumental to queer people that is now lost to history, whether poorly preserved or the victim of gentrification.

The continued impact of the pandemic further increases the precarious existence of queer spaces. Think of venues where queer art lives: independent bookshops, libraries, museums, galleries. These are such spaces that we cannot take for granted.

But there’s hope, too. Hester imbues the places he explores with the magic they once held in precious, ephemeral moments. His work goes a significant way to ensure queer historical places will not be forgotten.

Rear view of Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, 199? by Howard Sooley. Courtesy of the publisher.

Queer spaces aren’t just found, they’re also made; we make them, over and over if necessary until everyone has a place.

Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories, Pegasus Books, 2024, p.341.

The title Nothing Ever Just Disappears is itself a moving tribute. It comes from a short story by Sam D’Allesandro, who died from AIDS-related complications in 1988.

Again, the care Hester takes is evident. D’Allesandro died far before his time, and the little writing he published is out of print. Yet, with this biography named in his memory, it ensures that a once-lost piece of queer history will not, in fact, disappear.

Get your copy of Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories on the publisher’s website.

Book cover of Nothing Ever Just Disappears: Seven Hidden Queer Histories. Author’s website.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!