In recent years, the Uffizi complex in Florence, which encompasses the renowned Uffizi Museum, Palazzo Pitti, the lush Boboli Garden, and the soon-to-be-reopened Vasari corridor, has become a thriving hub for a growing number of contemporary art exhibitions. With a diverse array of global artists and a medley of artistic mediums, contemporary art has seamlessly woven itself into the museum’s program, adding a vibrant layer to an already remarkable cultural tapestry.

Among the latest projects, Wang Guangyi’s solo exhibition, Obscured Existence, housed in the evocative Andito degli Angiolini section of Palazzo Pitti, emerges as an exemplar of artistic intrigue. The exhibition, the first solo show of the artist in Italy, stems from a long collaboration that saw the direct involvement of the artist himself, together with the two curators, Demetrio Paparoni and the Uffizi director Eike Schmidt. Reflecting on the museum’s collections and working on site-specific works, Obscured Existence marks a pivotal chapter in the artist’s illustrious career. So significant is this exhibition that one of Wang’s self-portraits, on display in Florence, will become a permanent addition to the museum’s self-portrait collection.

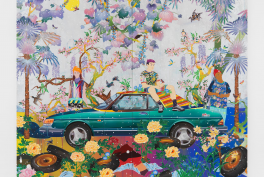

Wang Guangyi, Obscured Existence, exhibition view. Photo Courtesy of the Uffizi Gallery.

A look at rituals and ancient techniques to understand Wang Guangyi’s practice

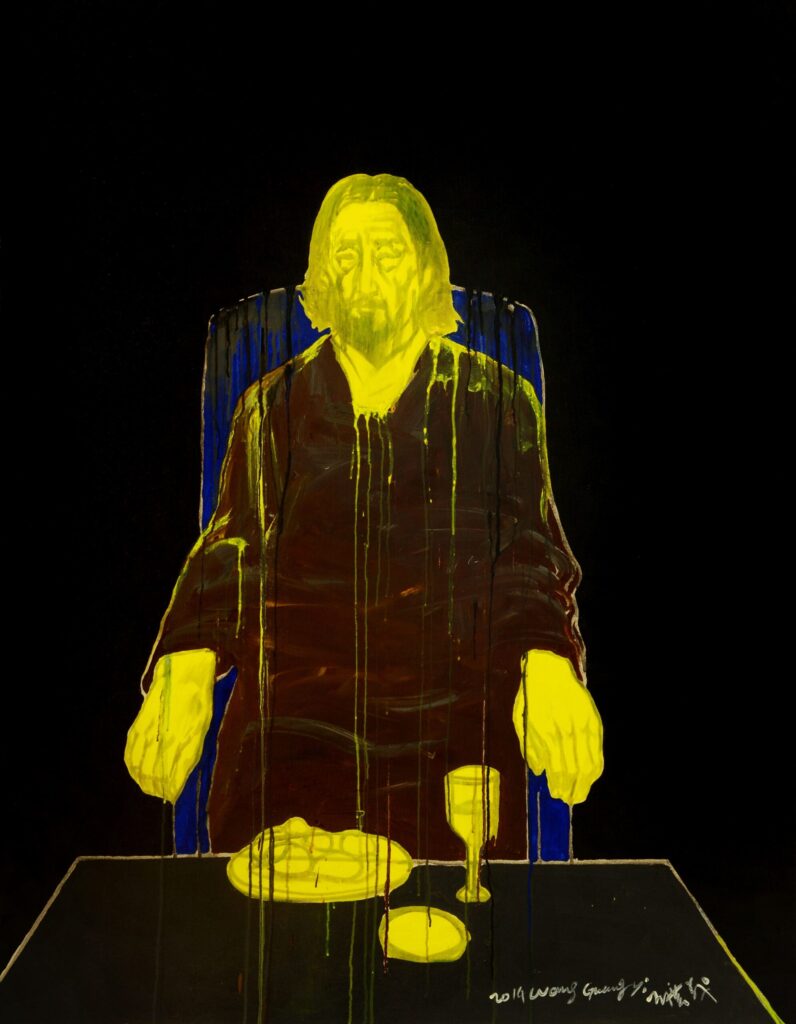

The exhibition showcases 28 paintings from four distinctive series, offering insight into the prevalent themes woven throughout the artist’s production. Originating from Heilongjiang province in northeastern China, the artist’s work is deep-seated in traditional techniques and resonates with ritualistic practices reminiscent of shamanic traditions that persist in the region. Ritual is, in fact, a central theme of the exhibition. In series such as Daily Life and Ritual, the artist analyzes the repetitiveness of everyday gestures, which in his work become small rituals performed collectively from the privacy of everyone’s own home.

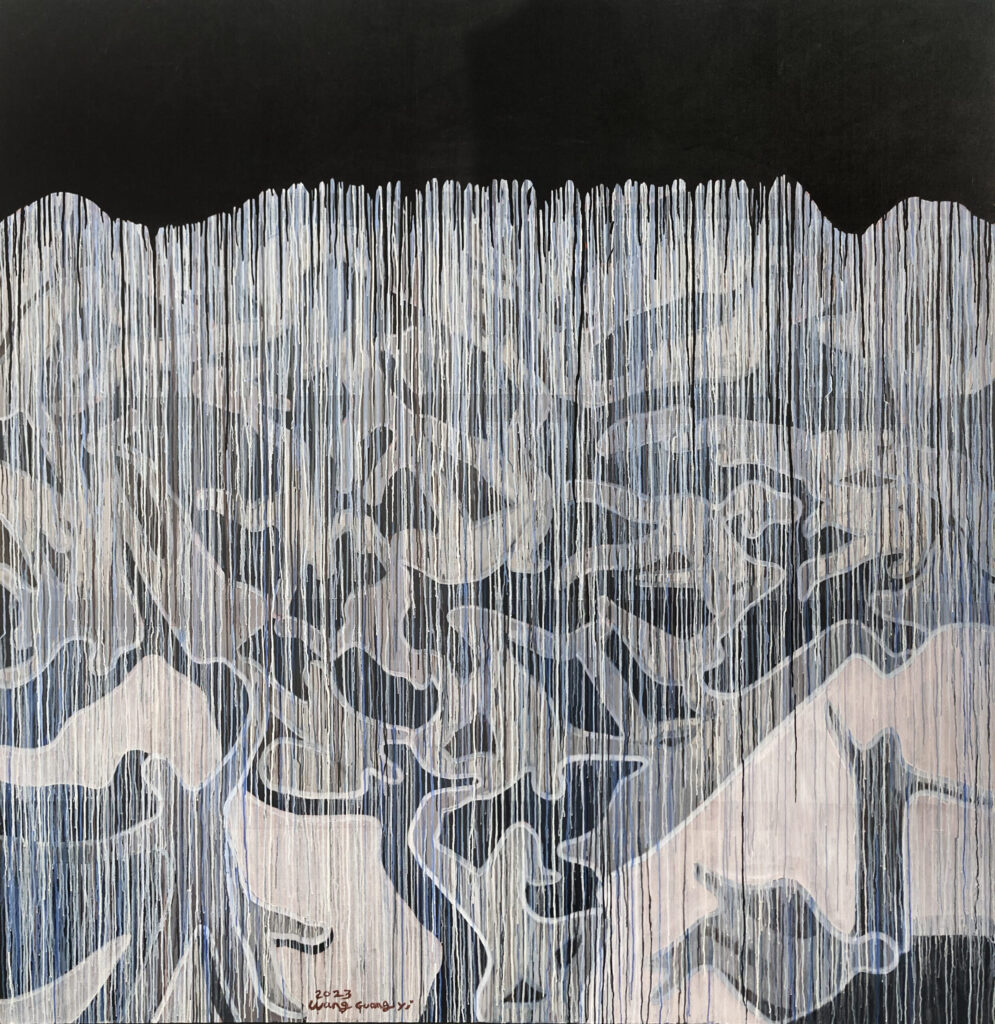

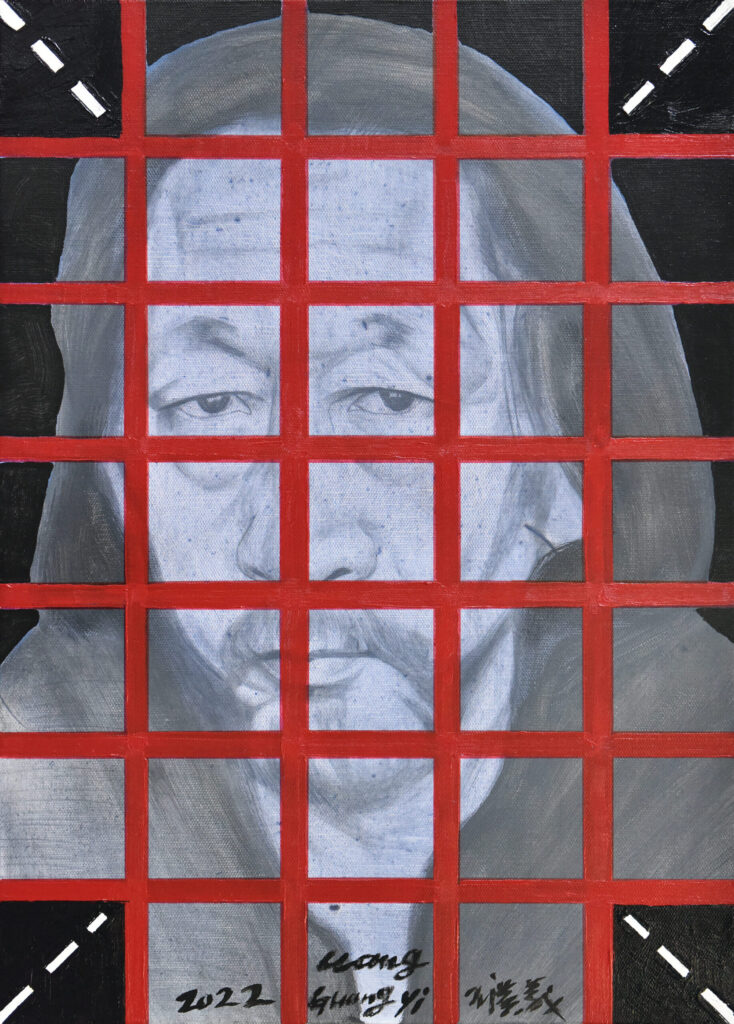

Traditional techniques and historical influences are the other nuclei around which Wang Guangyi’s practice develops. The Obscured Existence series, on display in this exhibition, employs the ancient Wu Lou Hen (屋漏痕) technique, which bathes the canvases and their subjects in dripping paint. This technique simultaneously serves as both a screen and a mirror, creating a mesmerizing separation between the viewer and the depicted scene, inviting a fresh perspective. The last series of works in the exhibition embraces yet another traditional technique, the grid. This practice, commonly used in both Eastern and Western traditions to enlarge images, transcends its functionality in Wang’s practice to become an integral part of his work. It fascinatingly interposes itself between the subject and the viewer, profoundly altering our perception of the art before us.

Despite the modest number of artworks on display, this exhibition masterfully encapsulates the essence of Wang Guangyi’s artistic genius and offers an ideal introduction for the Italian public to his extraordinary body of work.

Wang Guangyi, Obscured Existence, exhibition view. Photo Courtesy of the Uffizi Gallery.

On the occasion of the exhibition, we talked to the artist and the two curators about the project. What follows is a three-part conversation with Wang Guangyi, the curator Demetrio Paparoni and the Uffizi Director and curator of the exhibition Eike Schmidt.

Carlotta Mazzoli: Let’s start with the artist. In your works, you often portray common situations and objects, offering an interpretation of history through small gestures. However, contemporary society seems to impose a constant pursuit of the exceptional, pushing for excessive performance. How does your work fit into this discourse? And on what themes do you ultimately want the viewers to reflect?

Wang Guangyi: I try to be disengaged from what is happening around me because I aim to be neutral in my evaluations. I consider my art to be completely personal because of the way I see the world. People’s perception of the world changes depending on where they come from and the culture in which they are formed. We are surrounded by objects we consider trivial and make automatic gestures to which we give no weight. Yet, trivial objects with which we are in daily contact can take on a sacral value, just as habitual gestures can manifest a rituality not unrelated to the dynamics of faith. Art can help remove obscure aspects of existence, but it is a complex process. Where a racial background is manifested or cultural differences are emphasized as distinctive traits of superiority, it is very difficult for this process of removal to take place.

Wang Guangyi, Fallen Angels, 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CM: Another recurring theme in your production seems to be the past, from the comparison with the great masters of Western art to the use of traditional Chinese painting techniques, such as Wu Lou Hen. How do you relate to the past? Is it a source of inspiration for you or something to break free from? And how does this reflect in your works?

WG: Towards history, I have an attitude that could be described as nihilistic. Above all, I have a nihilistic attitude toward what we normally call “art.” Nihilism is a good medicine. Underlying the existence of contemporary art is probably what Herzinha calls the “spirit of play” and what Gombrich calls “schematic revision.” In light of these theories, which I espouse, I think that one should approach the art of the masters of the West and the East with an attitude that is not unserious but not too serious, either. When I approach art, I keep myself balanced between a serious and a playful approach. I consciously combine these two attitudes. It is thanks to this attitude that I am able to express my thoughts as a contemporary artist.

CM: The works on display are often almost monumental in size, with canvases reaching up to three meters. The subjects seem to expand in them, and the spaces lack precise connotations as if to maintain a nearly universal neutrality. Do you believe that viewers can recognize themselves in your works? Or do you rather consider your painting to be exclusively personal, an expression of your particular private universe?

WG: My paintings are closely connected to specific lives and feelings. The values inherent in the lives of individuals should not be thwarted by cultural and political diatribes that tend to spectacularize art, which, being an artistic tool, should be treated as such.

Wang Guangyi, Daily Life No.3, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CM: Let’s now move to Demetrio Paparoni, curator of the exhibition. Obscured Existence revolves around four main themes that emphasize the concept of the rituality of everyday gestures. How did you arrive at the definition of these themes? And how do they relate to each other and to the public?

Demetrio Paparoni: In the West, Wang Guangyi is best known for the paintings of his Great Criticism series, which identify him as a pop artist. In reality, he has an attitude that is anything but pop. The vast pictorial production preceding the works of Great Criticism has a strong relationship with Western art history. He also has an intense production of large multimedia installations. But he has never stopped painting, always animated by a certain restlessness, typical of experimenters. Certainly, there are constant shifts on a linguistic level in his work, but fundamentally, his interest is always in themes such as transcendence, faith, and the relationship with phenomena that are hidden behind the apparent, behind things, even the most banal. It should not be forgotten that there is also a mystical component in his work, which in some ways brings him into line with Western artists such as Joseph Beuys or James Lee Byars.

Personally, I had the feeling that this exhibition in Florence represented a psychologically important moment for the artist: he has always looked at the great masterpieces of Western art and, with this exhibition, he was offered the opportunity to exhibit under the same roof that houses the works of our great masters. Exhibiting paintings created in recent years was, in fact, a sentimental choice.

CM: You mentioned how the exhibition was a great opportunity for the artist to exhibit alongside some of the greatest masters of all time. How have the history and specifics of Palazzo Pitti influenced the definition of this exhibition? In other words, the works presented here largely reference daily and domestic life. Similarly, Palazzo Pitti was the residence of the Florentine Grand Dukes and the Savoy family. Is there a connection between the works on display the private nature of the palace, and its history as a “domestic residence?”

DP: The relationship with the exhibition space was filtered by the fact that the exhibition, in addition to being curated by me, who have worked with him constantly for more than 20 years, is also curated by the director of the Uffizi, Eike Schmidt. I am a contemporary art critic who also deals with art of the past, Schmidt is a historian of ancient art who also deals with the contemporary. These are two profoundly different attitudes. The fact of being able to have a relationship with a historian of Schmidt’s caliber was very intriguing for the artist, who, as I said before, has always had a strong interest in our art history.

Wang Guangyi, The Shadow of Memory No.1, 2021. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CM: What were the major challenges in organizing this exhibition?

DP: Schmidt showed him some subjects of paintings in the Uffizi to use as the basis for new works. It is one thing to do work because you feel the need, quite another to do it because someone asks you to. Obviously, there was no imposition, but the dialogue was intense. This was definitely a challenge. The first version of the work referred to Medusa did not convince me, and I told him with caution, as one who does not want to be offensive. You know, artists are often touchy. Well, there was no tension from his side, and Wang Guangyi put his hand to the work again to make a wonderful new version. That’s on the one hand. Then, there is also the interest he has in philosophy. Here again, as in the past, the exhibition offered an opportunity for the artist to exchange views with Elio Cappuccio, an Italian philosopher with whom he has been in dialogue for more than a decade. The fruit of this further encounter between the two is their conversation published in the exhibition catalog.

Personally, I feel under exam every time I make an exhibition or write a text. Wang Guangyi, on the other hand, gives me the feeling of a person who faces every challenge with the utmost serenity. I suppose that was the case this time, too. But I don’t know if that was really the case. If there was something in him this time that, as he himself would say, goes beyond appearances.

CM: Lastly, let’s talk to Eike Schmidt, art historian, director of the Uffizi Gallery since 2015, and curator of the exhibition. As you stated, the Uffizi carries out a dual program aimed at studying the past but also promoting the contemporary. How does Wang Guangyi’s exhibition fit into the Uffizi’s programming? And more generally, how does the museum approach contemporary art?

Eike Shmidt: In regards to contemporary art, from time to time, we invite international artists to engage with our collection, analyzing some aspects that are particularly interesting to them or prevalent themes in our collection. This was the case, for example, for the large Cai Guo-Qiang exhibition, which we developed in 2018. From this point of view, the Uffizi Gallery is geographically open, and over the years, we have worked with artists from all over the world. In addition to the aforementioned Chinese artist, we were, for example, the first Italian museum to have two exhibitions dedicated to African artists, one from Congo and the other from Ethiopia. In terms of collection, the museum does not collect contemporary art, with the exception of self-portraits, but organizes temporary exhibitions.

For the Wang Guangyi exhibition, I got to know his work during a trip to China, and together with Paparoni two years ago, we started planning this show to be included in the Uffizi program. We were fascinated by his approach, especially in relation to spaces halfway between personal and public, such as those of Palazzo Pitti, as well as the theme of the self-portrait. In fact, in general, the self-portrait is a way for artists to unmask themselves, to communicate in a visual way what is important to them. For Wang Guangyi, the self-portrait is a mask that allows him to invite everyone to imagine themselves as protagonists of his paintings. In his work, the artist is seen in a shamanic function on the basis of his training and cultural background. In fact, the artist comes from north-eastern China, where the tradition of shamanism is still strongly present today.

Wang Guangyi, Self-Portrait, 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist.

CM: The self-portrait therefore appears to be a recurring theme in Wang Guangyi’s production, and as mentioned above, the exhibition presents several of them. However, tell us about the self-portrait that was chosen to enter the Uffizi collection at the end of the exhibition. What criteria guided the choice of this work?

ES: The artist actually portrayed himself in several scenes among those on display in the exhibition. However, most of the self-portraits in our collection are smaller in size and, more specifically, represent the artist’s face, with very few exceptions. Thus, when the artist himself proposed donating a self-portrait to the museum, he opted for a format based on more traditional, smaller-sized models. I myself encouraged him in this sense, as the small format focuses more specifically on the subject and the very theme of the self-portrait in itself.

In his case, we opted for a self-portrait with a grid placed in front of his face, the same one he also used to portray Mao Zedong. This grid implies an ideal monumentalization of the subject, even if it does not use a huge format of the canvas. In fact, the grid, even in Western painting, was used from as early as the 15th century onwards to enlarge preparatory drawings, especially in the creation of large public works, such as frescoes. This technique applied to the canvas highlights the subject and virtually enlarges it without necessarily increasing the actual size of the support.

Wang Guangyi and Eike Schmidt, 2023. Photo courtesy of the Uffizi Gallery.

CM: To conclude, let me ask you one more question about the self-portraits section of the Uffizi collection. This is the only nucleus in which the Uffizi Museum collects contemporary works. As anticipated, in this section, as well as in the temporary exhibitions, the museum opens up to artists from any corner of the planet. Can you tell us how this section was born and how it is evolving?

ES: As you mentioned, the self-portraits section is the only one in which we collect contemporary artists. In fact, since the mid-17th century, the most renowned artists active first in Europe and then internationally have been invited to donate a self-portrait to the Uffizi. The first to inaugurate this collection of self-portraits was Cardinal Leopoldo, whose personal collection merged into that of the Uffizi after his death. The cardinal himself collected not only self-portraits of Italian or Tuscan artists but also self-portraits of international, Flemish, German, and French artists. Under Grand Duke Cosimo III then, the Uffizi embraced the entire known world at the time, including the first American artists who arrived in the collection at the end of the Eighteenth century. To date, this collection includes European, American, but also Asian, and African artists. Diversity has been in the DNA of the collection since the very beginning.