Observation as an act of creation — whenever you look, you’re painting a perception: Realizing that we are painters of our impressions is as empowering as liberating — and, like in every art form, there’s a way to perfect your skill.

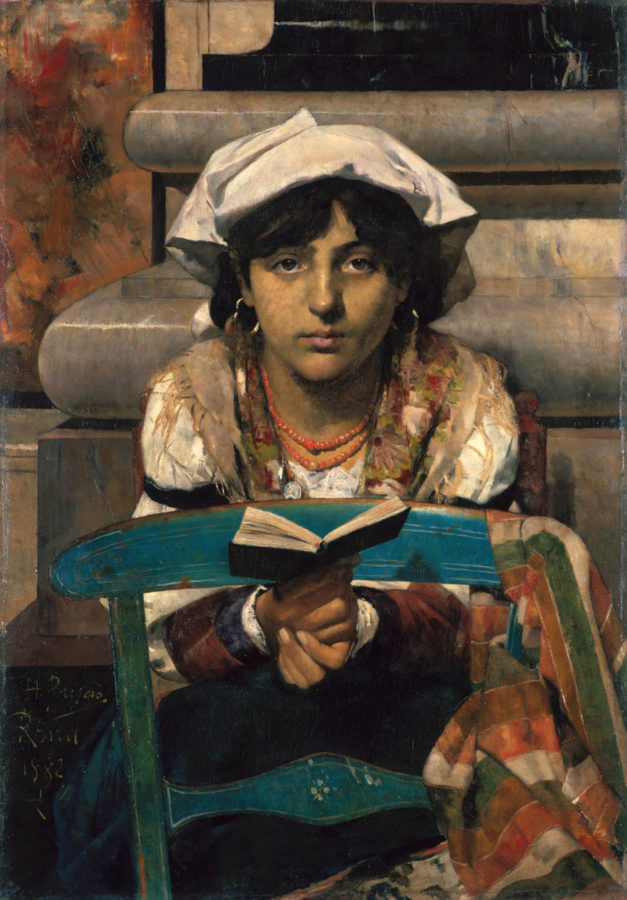

Henrique Pousão was a naturalistic painter who deeply understood the power of learning how to see- to patiently allow the eye to catch up with every angle, to suspend judgment and isolate the different impulses that suggest a conclusion — he considered observation as an act of creation.

To paint a true portrait of your surroundings, you must realize how much your own conditionings affect the impressions you gather. Understand your mind-mold — the framework in which you operate this complex interplay of psychological representations and social conditionings that compose your “painting“: like, how is this reasoning a product of my education; how is it being shaped by emotive responses; how much of it is triggered by fears; can my conjectures be based on hopes and dislikes; is my mindset embedded in stereotypes…?

Facing the fact that we are painters of our impressions is as empowering as liberating: it offers the world as a palette to explore, strengthening our ties with everything upon which our mind rests, setting observation as an act of creation.

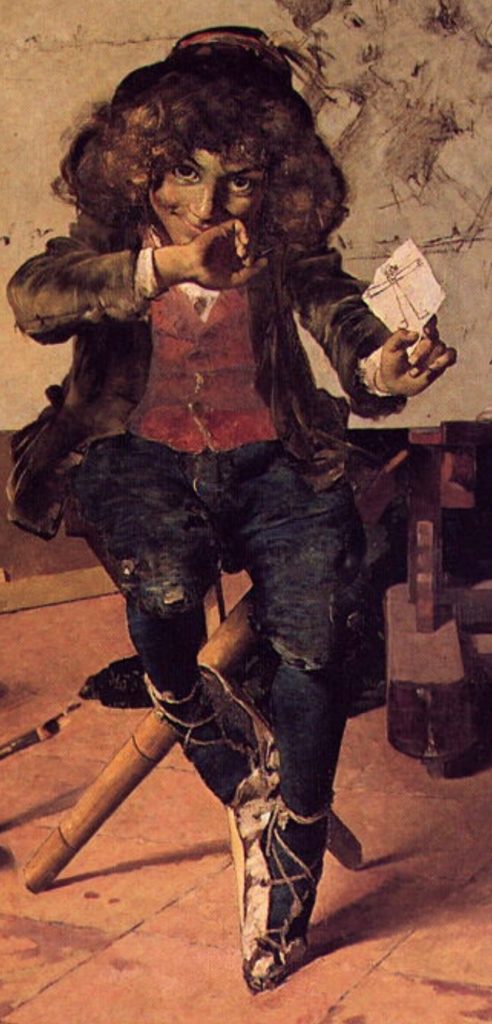

TAKE A GOOD LOOK AT HIS PAINTING:

This young boy, joyfully staring at us with mellow eyes, taking a break from the stillness of posing, may be one of the most iconic, yet ignored, symbols regarding observation-creation.

It’s amazing how natural the pictured moment is. The scene couldn’t be less pretentious, the studio is perfectly ordinary, the kid sits in a relaxed and childish way, even the working environment is somewhat tranquil. It looks like we just walked in in the middle of the action, so our presence caused an Interruption, as we are caught by a delightful smile and two proud eyes staring at us waiting for approval. In fact, this painting is all about interruptions — the boy stops posing to show us his own version of himself, drawn on a little piece of paper; behind him, on the canvas, stands the painter’s sketch for the child’s picture: so, how many painting are here, and what can they teach us about observation as an act of creation?

1. The Child’s Sketch

The boy shows no respect for the rituality of painting. Turning his back to the canvas while changing his pose, the child interrupts the painter to show a rippled piece of paper. He doesn’t do it out of malice, nor is it the result of ignorance, but a light-hearted disregard for convention: why show reverence to something just because it’s drawn on a proper canvas; why not be proud of a piece of paper if it’s saturated with the same matter as the masterpieces — pure creativity.

The child doesn’t aspire to rebel against anything, there is no duty in his creation, yet the force he is driven by shows no mercy to authority, it is empowered by the value of curiosity and excitement in itself. All principles are new and noble, all approaches worth considering. “Truth” is but a toy to be played with, open to amusing construction, while ideas are molded, tossed, mixed and joint like pieces of LEGO.

Nothing is too absurd, nothing is too serious, nothing is too evident! Had not there been a child in people’s attitude to observation as an act of creation, then Galileo Galilei would never have dropped balls from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, disclaming the solemn Aristotelian theory of gravity; nor would have Hennig Brand boiled his own piss to discover phosphorus; nor would anyone have conceived the idea of a cat being both alive and dead at the same time — it’s all about freedom and innocence, which allow levelling of all that was thought and seen to a common ground where new values and concepts can flourish: interrupting authority fuels pure creativity.

2. The Canvas Draft

The draft presents a perfected version of the boy, nobler and more beautiful: his wide potato nose is portrayed as small and delicate; the hat on top of his ragged clothes even seems aristocratic, his meditative head rests upon a steady hand — there is an overall feeling of idealization.

Somewhere, right now, there’s a small group of people working away in a garage, dreaming about changing the world if every single thing goes smoothly — some of them eventually will! — If the founders of Apple, Google or Microsoft had never dreamed of the most positive possible scenario, then how would have they aspired to be what they’ve become?

While playing with an idea, one has the freedom to extend it into it’s most extreme scenario, elaborate a whole mental experiment, or invent completely new laws and models — here the painter interrupts the boundaries of reality to go beyond the limits of his physical theme.

This is when we don’t think about how things are, but the question about how they could be. This thought functions as an arrow, pointing to a distant bright destiny that we ought to follow — at the dawn of agriculture envisioning a golden field of wheat; a slave dreaming of equality; a deaf wishing to hear…

Though the complete opposite is also relevant, by warning us about just how bad something can become: these are the so-called Utopias and Dystopias, and they are both a great compass and magnifying glass when operated by Idealization.

3. Henrique Pousão’s Painting

There was a moment when Pousão understood he would not be satisfied with what he was portraying: that he would be missing something if he kept on painting the initial, sketched, version of the child’s portrait — so he Interrupted it.

Seeking the noble beauty he had first envisioned would cost him authenticity: by pursuing the classic canon — the stylised portrait that is set to elevate Art from the mundane, with its picturesque backgrounds and romanticised beauty — Pousão would then be blind to a shy smile concealed by proud eyes; he would never notice the elegance with which the child’s ragged old shoes touch the ground like a ballerina, and the chance to capture a manner so subtle, so enriched with truth, would be lost.

To roar back at the loud command of expectations — both our own and of all the others — is to understand that we too take part in shaping the concepts that are so often taken as truth. It’s to widen possibility, looking beyond present conventions and morals, molding the structure that will eventually change our own views, in this ever mutable cycle of transformation.

The ability to sacrifice one’s present vision and opinion is the great virtue of adaptability. To be always permeable, taking pride in once being wrong and honouring not being sure of anything — embracing reality in its full scope, even when contradictory or hurtful, is to be synchronised with its complexity: facing ugliness with a wholesome disposition is what got us using viruses, infectious agents responsible for taking countless lives, to cure such diseases as cancer.

4. Your Observation as a Painter

Though nothing in the painting has moved, something has changed — it’s no longer the same painting you’ve first seen — it has been painted over: for every new observation a pigment has been added; colours been deepened; shapes widened.

In any sport, game or activity, enjoyment arises from taking part in it, in being committed to imprint your individuality, feeling and being engaged. While your attention has been bombarded with ideas and observations, you stand, facing the canvas, in the position of a painter — ready to pick up the brush Pousão so thoughtfully left within your reach at the left of the canvas — reminding that it is up to you to give colour to any observation.

Facing the fact that we are painters of our impressions is as empowering as liberating: it offers the world as a palette to explore, strengthening our ties with everything upon which our minds rest, setting observation as an act of creation.

Besides, in a strange way, the freedom granted for a painter to enthusiastically and with imagination depict his views, doesn’t set him apart from reality — quite the contrary, setting observation as an act of creation allows for a stronger connection and sensibility with the truth, as it promotes inquiry and critical sense — the absolute contrary of Apathy: the great responsible for neglecting one’s relation to knowledge.

If you weren’t a painter, then Pousão’s masterpiece would have been less yours, but still an ever-changing piece.

By keeping in check Pousão’s lessons things appear less solid and more like an interplay of invisible fabrics, a tissue of colours filled with nuance, waiting to be experienced from every angle.

If everyone is looked at as a painter and observation as an act of creation, then discussions are more fluid, people more tolerant, observation more engaging, and things are just, overall, a lot more interesting to look at.

Find out more:

- This article is part of a bigger reflection: to read its Full Preamble click here.

- on psychological representations and social conditionings

- on Galileo Galilei and his experiment

- on Hennig Brand boiling his own urine

- on the idea of a cat being both alive and dead at the same time

- on playing with paradoxes;

- on elaborating mental experiments

- on inventing new laws and models

- on Utopias and Dystopias

- on viruses, and how they can cure

- on this very majestic penguin