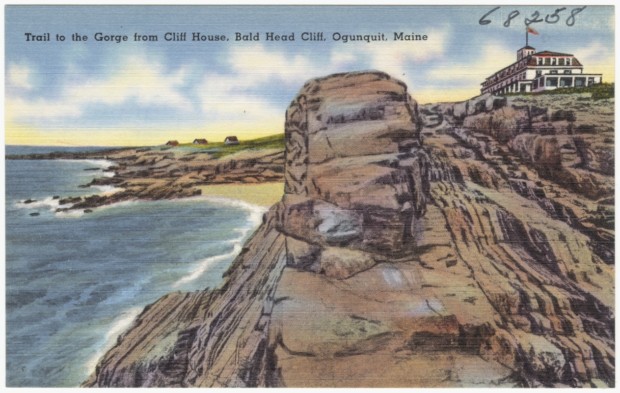

The Abenaki people native to southern Maine knew of their homeland’s allure long before their European successors. The word “ogunquit” – which became the name of a small shipbuilding community on the state’s southern border – means “beautiful place by the sea” in their language.

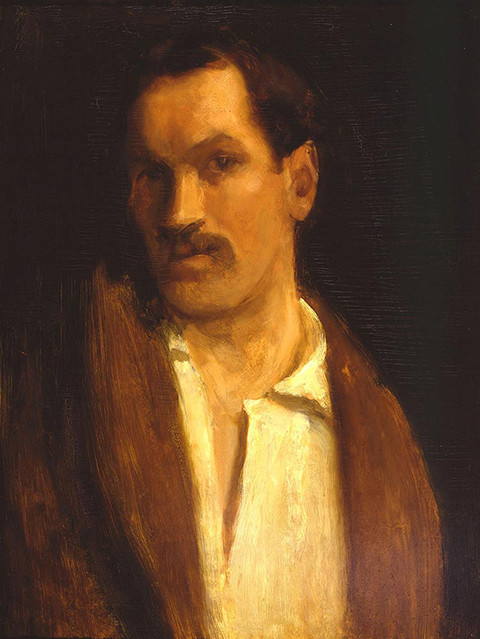

By the early twentieth century it had become a popular destination for artists who wished to capture the landscape’s natural elegance. The community came to foster two very different schools of art: the Ogunquit Summer School of Drawing and Painting (founded by Charles Woodbury) and the Ogunquit Summer School of Graphic Arts (the brainchild of Hamilton Easter Field, a student of Woodbury’s).

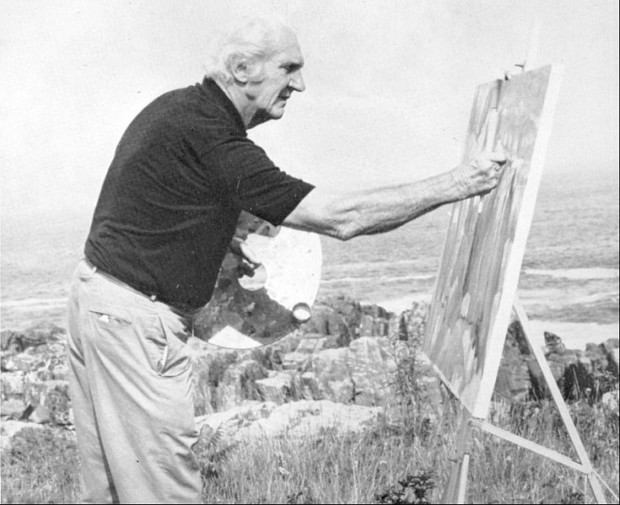

The pastoral farmland and rough-hewn seaside served, for Woodbury, as inspiration to create a truly American style of painting. A native of Lynn, Massachusetts, his work drew heavy influence from the Boston School. Similar “regional impressionist” ideals spread across the East Coast during the birth of Impressionism in Europe.

In 1898, Woodbury opened his aforementioned art school. Unprecedented at the time, his summer classes were a unique alternative to attending a traditional (and strict) art academy. Here he taught his “art of seeing,” which emphasized subjectivity in art – how things seem rather than how they appear.

He and his students produced honest depictions of local life and landscape, drawing the attention of Robert Henri (of the New York-based Ashcan School) and Edward Hopper. They rejected modernist innovations, and in doing so often became innovators themselves: Woodbury forever changed the typical viewpoint for marine paintings, choosing to present his seascapes midway over the waves as though the viewer were floating above them. He went on to be considered by some the greatest marine painter since Winslow Homer.

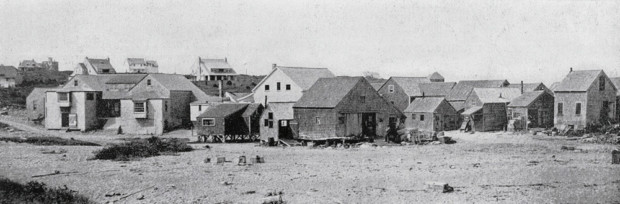

In the summer of 1902, Hamilton Easter Field – along with his protege Robert Laurent (the sculptor, 12 years of age at the time) – arrived in Ogunquit looking for a summer residence. Instead, he bought a row of shacks that he started renting out cheap to artists. This was the first step towards creating a true artist colony.

In 1911, Field founded his own summer art school. Unlike Woodbury, he was a strong proponent of modernism. Often times he and his students worked inside with nude models, whereas Woodbury’s students were out-of-doors. Though they were opposing thinkers, the two artists and their schools coexisted peacefully, further fostering an artistic community in Ogunquit.

The area’s landscape drew the first, let’s say, more traditional artists, who then attracted their modernist successors. Soon enough, Ogunquit was a thriving, even lively seaside town – whose party scene in the 1920s through the 1940s became a thing of legend. It was a true paradise for those who sought family among their fellow artists.

In 1953, Henry Strater – a former student of Woodbury – opened the Ogunquit Museum of American Art (built, coincidentally, on a plot of land purchased from his teacher’s family). The museum was, in many ways, a response to the growing popularity of contemporary writers. Strater wanted to spread awareness about modern American painters, particularly his friends in the northeast.

To this day, both the museum and the legacies of the painters whose works it displays are a testament to the innovation and creativity born in Ogunquit. This quaint, quiet, “beautiful place by the sea” was an inspiration to many of the greatest – yet perhaps more unheard – artists of the modern era. It remains as not only a reminder of the strength to be found in artistic community, but as a continuing influence on the minds and hearts drawn to the seaside.