Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

21 October 2024 min Read

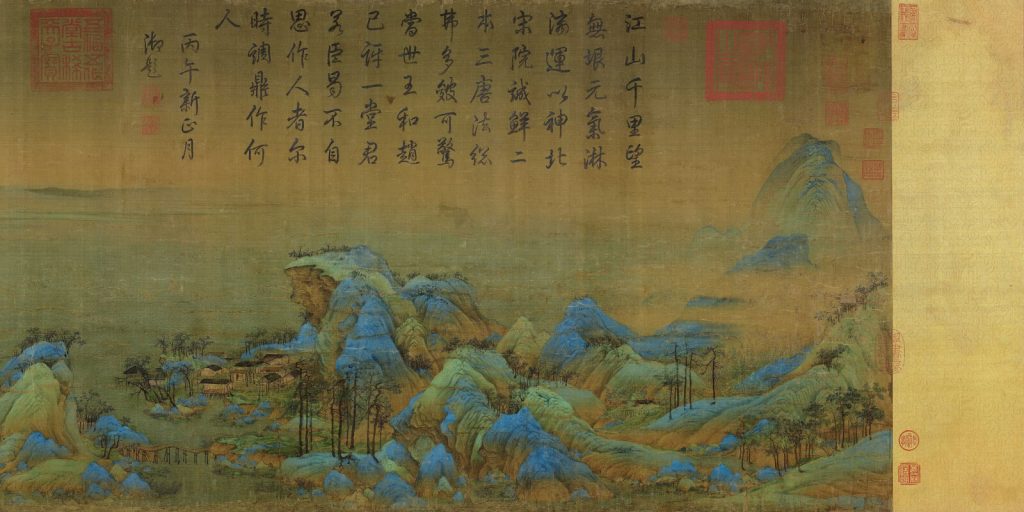

Wang Ximeng’s One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains is a masterpiece of the Northern Song dynasty and of the larger history of traditional Chinese painting. It interacts with the viewer in a way rarely found in Western paintings.

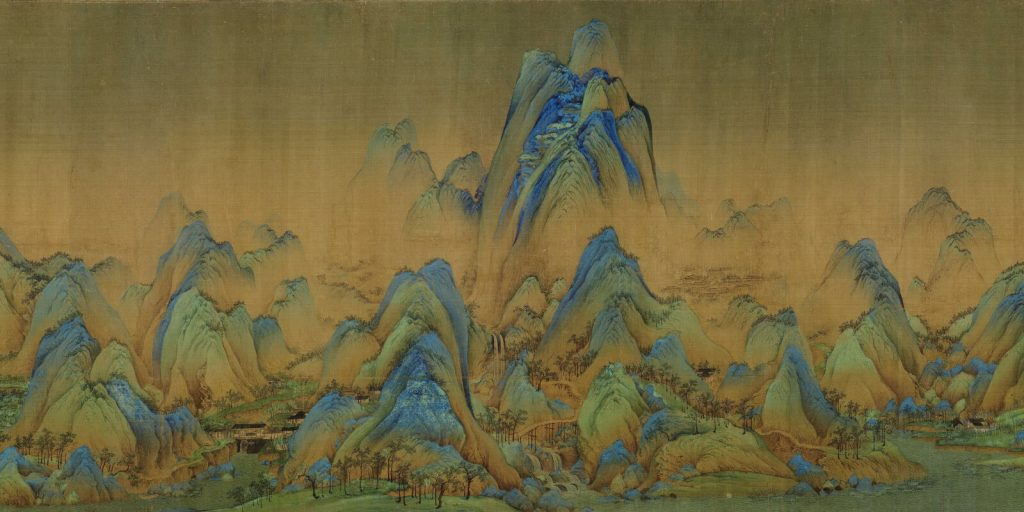

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

The Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) was one of the greatest periods of Chinese painting. It experienced many cultivated emperors who patronized budding talented artists and established art schools. Emperor Huizong (r. 1110-1126) was one of the most notable since he was a skilled painter and calligrapher in addition to being a generous patron. He is also believed to have been a personal tutor to Wang Ximeng (1096-1119), a famous but short-lived painter, who became a celebrity at the Song Huizong court. Wang Ximeng sadly has only one surviving work, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains. It reveals the masterful skills of an artist talented beyond his years.

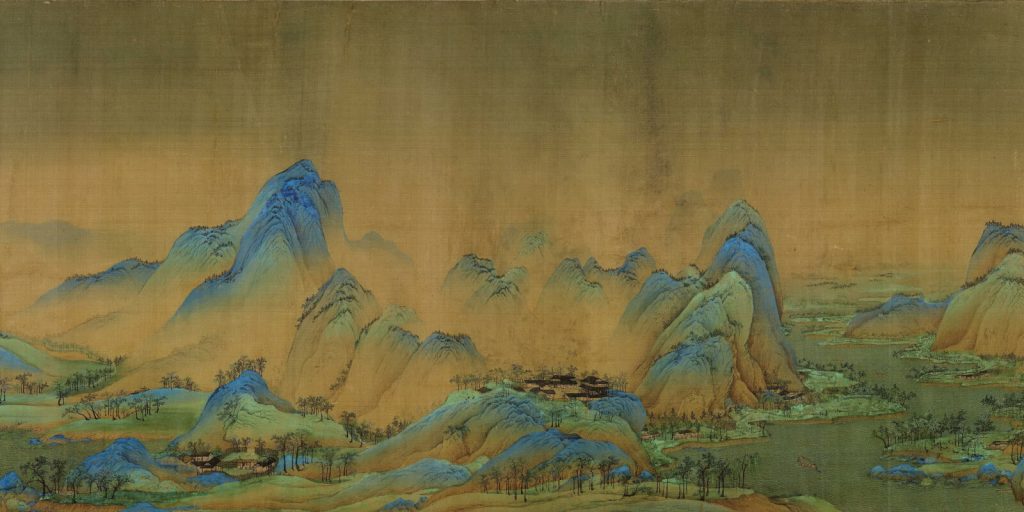

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Wang Ximeng painted One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains or Qianli Jianshan Tu in 1113 for Emperor Huizong who then immediately gifted it to the prime minister Cai Jing (1047-1126). The painting measures 51.5 cm high by 11.92 m long (20.27 in by 39 feet). Its materials are simple: black ink and ground pigments on a long silk scroll. However, the simplicity of its material elevates its compositional complexity.

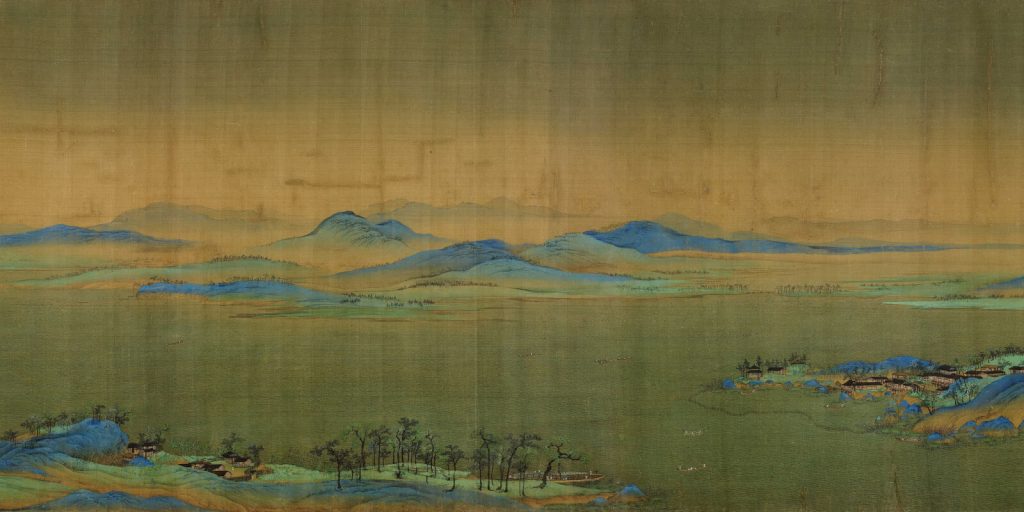

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

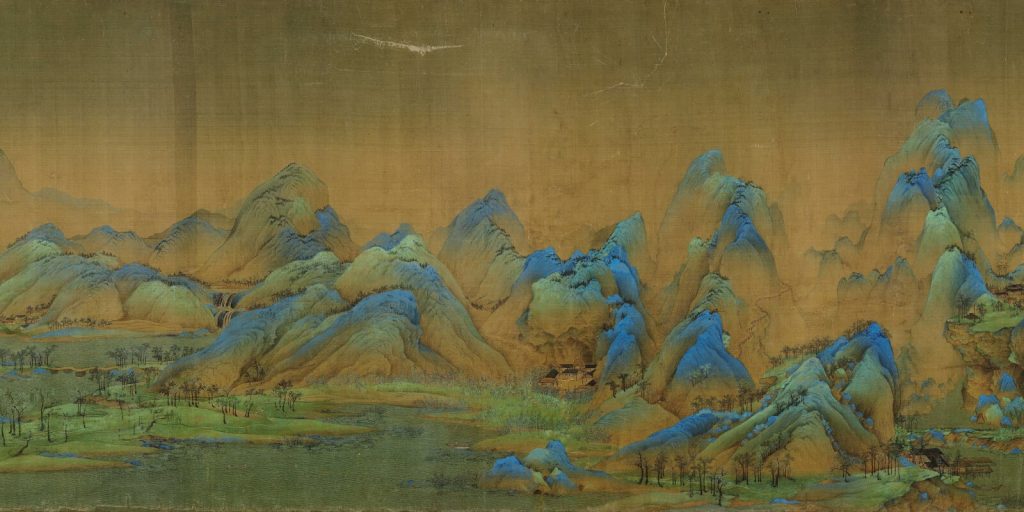

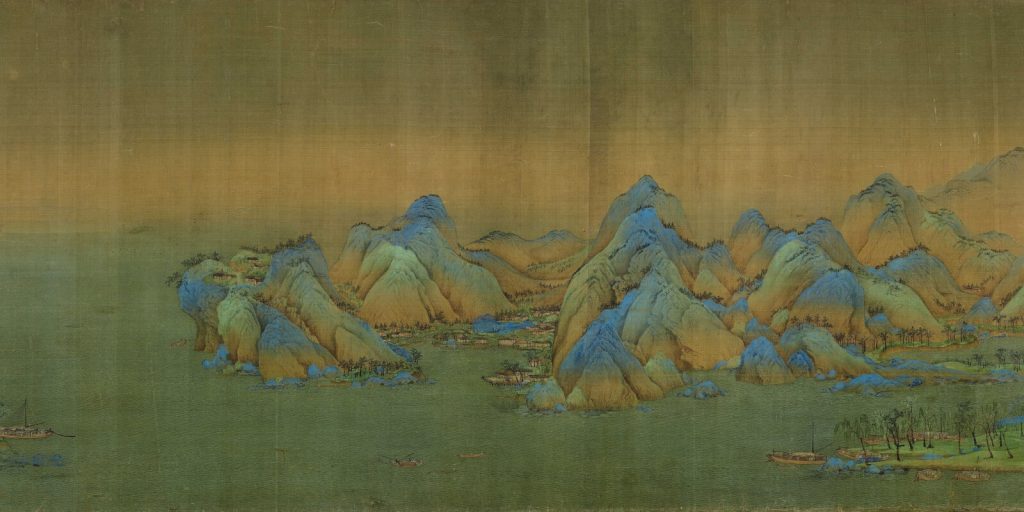

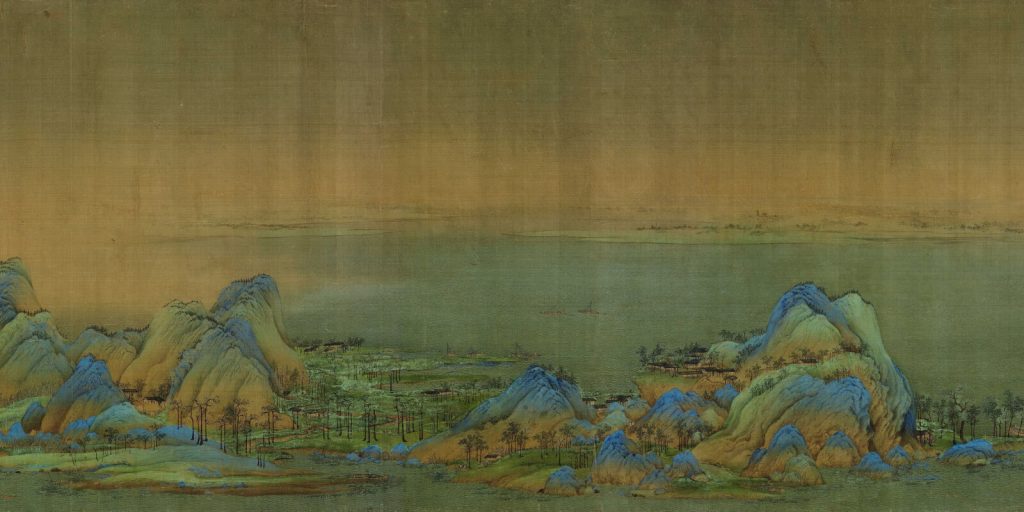

The expansive perspective is a panoramic view of a Southern Chinese landscape. The accuracy of the mountainous landscape implies that its creator, Wang Ximeng, originated from Southern China because only a native could be so familiar with its topography. The overall landscape is divided into six sections of mountains divided by water but sometimes linked by bridges.

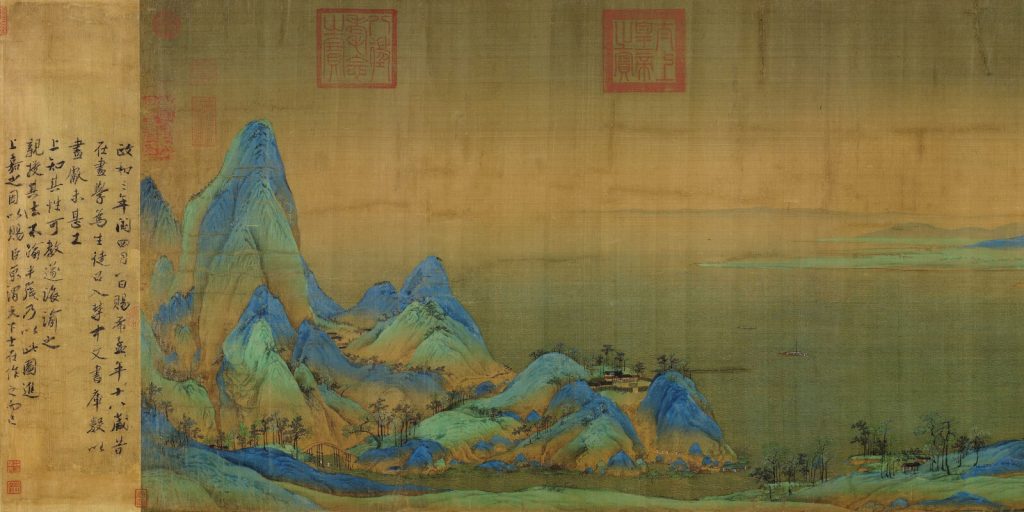

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Houses, trees, and figures punctuate the mountains and are shown from multiple viewpoints. The many angles add a shifting perspective so that as the viewer unrolls the scroll from right to left, the daily activities of the figures are revealed in a continuous but understandable narrative. The experience is similar to a passenger traveling on a modern train while viewing the landscape through the train car window.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

In addition to the multiple perspectives, the painting also uses the “Three Distances” formula so strongly promoted by the Imperial Painting Academy where Wang Ximeng was a student. The “Three Distances” concept fuses three visual angles to imply a panoramic view thousands of kilometers across without losing a sense of context. The first angle is gaoyuan or high-distance which is the visual space from the bottom to the top of a mountain. The second angle is shenyuan or deep-distance which is the visual space from the front to the back of a mountain. The third angle is pingyuan or level-distance which is the visual space spanning between two mountains. This fusion of height, depth, and level distance is an old Chinese painterly technique that was already practiced in the early Song (11th century) but perfected in the late Song (12th century).

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Adding to the painting’s perfection is the visually stunning blue-green landscape, or qinglü shanshui. The blue-green landscape was first practiced during the Tang dynasty (618-907), but it reached its apogee under the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). Vibrant azurite blue dominates the mountains’ peaks, bold malachite green dominates the mountains’ valleys, and pale ochre brown implies the mountains’ bases. It is a radiant arrangement that promotes color over the line so that there is a focus on light, shade, and texture rather than outlines, shapes, and forms. It is a profound and subtle examination of the visible world through sweeping scale, rich coloration, and expressive details. It positively exudes qui or energy that enlivens the viewer’s experience.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Wang Ximeng created One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains when he was only 18 years old and working as the personal librarian to Emperor Huizong. This remarkably talented young man created the artwork in 6 months while living in the capital city of Bianlian (modern Kaifeng). He is believed to have died at the tender age of 23 years because he suddenly disappears from official court records. However, during his brief artistic career, Wang Ximeng captured the courtly spirit of his age.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

The Song dynasty was a time when China was hemmed in by hostile powers such as the Mongols in the north and the Nanchao in the southwest. Song society turned inward and became more reflective of internal feelings and imaginations. It examined the Chinese world with a new curiosity as outward exploration and expansion proved difficult and nearly impossible.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

This reflective mindset gently coexisted with Daoism that promoted peace, order, and harmony. For Emperor Huizong, a Daoist practitioner and promoter, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains becomes an almost Daoist fairyland through its depiction of a peaceful and prosperous countryside.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains or Qianli Jianshan Tu is a metaphor for the emperor’s longevity and for the dynasty’s everlasting prosperity. It is a hope, a dream, a desire for a glorious future. Ironically and sadly, this dream was not to become reality. Only 13 years after the painting’s completion, Emperor Huizong would be forced to abdicate in 1126, and the Song dynasty would collapse in 1127. Prime minister Cai Jing, who owned the painting, was later revealed to be a corrupt official and denounced as a thief and traitor to the country. After his disgrace, he was mercifully banished to the countryside but mysteriously died 10 days later. Cai Jing is still blamed by many modern historians as a primary cause of the collapse of the Northern Song dynasty.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

The painting is a masterpiece of the Northern Song dynasty and of the larger history of traditional Chinese painting. It interacts with the viewer in a way rarely found in Western paintings. Due to its expansive size but minute details, it requires multiple viewings at multiple distances. The first viewing is at a far distance to observe its sweeping grandeur. The second viewing is at a close distance to observe its exquisite features. The third viewing is at a mid-distance to observe its overall impact: a beautiful blend of majesty and minutiae.

Wang Ximeng, One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Song dynasty, 1113, ink and color on silk scroll, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Wang Ximeng is underrepresented in the history of great Chinese artists simply because he has no other known works surviving today. His art career is a lost career. It is a figment upon the imagination of what could have been. Imagine if only the Mona Lisa existed to represent Leonardo da Vinci’s complete career. Would Vermeer be cherished if only his Girl with a Pearl Earring survived? Would museum-goers be so enthusiastic for Vincent van Gogh if there was only one Sunflower presented? It implies that history and humanity have lost countless great artworks due to wars, disasters, and neglect. How many were lost? Wang Ximeng and his One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains is just one example of a masterpiece beating the odds.

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Kavanagh, Kevin. “Robert Armstrong: Three Distances, 3 – 26 September 2020.” Exhibition. Kevin Kavanagh Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

“One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains.” Collection. China Online Museum. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

“Panorama of Rivers and Mountains.” Collection. Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

Pletcher, Kenneth. “Huizong.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 1 January 2023.

Sullivan, Michael. Arts of China. 5th ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008.

Zhang, Peter. “Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains.” Edited by Jie Chen. Shanghai Daily. 25 October 2017, section Art & Culture.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!