Marian Henel—Tapestries and Madness

Marian Henel’s tapestries are huge. The largest one measures over 6 m in length and 3 m in width (19 ft. 8 in. by 9 ft. 10 in.). Created in the...

Zuzanna Stańska 25 November 2024

From the ancient period through the 18th century, European Catholics and Orthodox Christians displayed and maintained bones of the deceased to honor the dead. Though their aesthetics might defy today’s sensibilities, ossuaries (buildings, sites, or even boxes holding the bones of the deceased) remind us of our mortality and serve as a space to ponder what will happen after the soul leaves the body. A moving tribute to the dead or a macabre decor? Read on to discover seven of Europe’s bones churches.

Carlo Giuseppe Merlo, San Bernardino alle Ossa, completed in 1776, Milan, Italy. Photo by Einaz80 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The church of San Bernardino alle Ossa of Milan, Italy, is a most impressive ossuary. The site has a history of storing human bones long before San Bernardino alle Ossa was built in 1776. In 1210, a cemetery nearby ran out of space, and a bone chamber was built. In 1269, a small church was built beside the room. Then, in 1679, both were renovated and expanded.

However, in 1712, the church was destroyed and replaced by the current larger church dedicated to Saint Bernardino of Siena. Carlo Giuseppe Merlo designed the church and completed it in 1776. Today, San Bernardino alle Ossa is best known for an ossuary showcasing the craftsmanship and orderliness of Mannerist architecture.

Sebastiano Ricci, Triumph of Souls and Flying Angels, 1695, San Bernardino alle Ossa, Milan, Italy. Photo by Einaz80 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The ossuary is octagonal in floor plan and comprises several chapels with paintings from the 16th through the 18th centuries. The ossuary’s vault contains the splendid 17th-century fresco Triumph of Souls and Flying Angels by Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734). The pendentives of the vault are decorated with images of the Holy Virgin, St. Ambrose, St. Sebastian, and St. Bernardino of Siena. Skeletal remains from individuals of an unknown number were incorporated directly into the chapel’s Mannerist decorations. The chapel’s walls, niches, and doors are filled with skeletal remains, in contrast to the muted tones of the painted surfaces.

Capela dos Ossos, Évora, Portugal. Photo by Alonso de Mendoza via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Capela dos Ossos (Chapel of Bones) is a popular monument in Évora, Portugal. The chapel was built by Franciscan friars next to the entrance of the Church of St. Francis, founded in the 13th century. It was inspired by the ossuary of San Bernardino alle Ossa. Above the entrance, a sign reads, Nós ossos que aqui estamos, pelos vossos esperamos (We bones that are here await yours).

The chapel’s interior walls are covered and decorated with disarticulated bones of around 5,000 individuals from numerous nearby cemeteries. The walls and eight supporting pillars come with carefully arranged bones and skulls held in place with cement. Two desiccated corpses used to hang in chains on a wall next to a cross.

Capuchin Crypt, Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini, Rome, Italy. Photo by Dnalor01 viaWikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Capuchin Crypt is a small area of six chapels beneath the Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini (Our Lady of the Conception of the Capuchins). Soil was brought from Jerusalem as ordered by Pope Urban VIII, making the space sacred and particularly desirable. Fr. Michael of Bergamo supervised the arrangement of the crypt’s bones. One of its six chapels, the Crypt of the Resurrection, houses an image of Jesus raising Lazarus framed with parts from a human skeleton. Another one, the Mass Chapel, does not have bones but the heart of Maria Felice Peretti, grand-niece of Pope Sixtus V.

In 1631, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, a member of the Capuchin Order, had the remains of thousands of Capuchin friars to be exhumed and transferred from their old monastery on Via dei Lucchesi. Bones from approximately 3700 people living between 1500 and 1870, many believed to be Capuchin friars and juveniles, decorate the Crypt of Skulls, Crypt of the Pelvises, and the Crypt of the Tibias and Femurs. The Crypt of the Three Skeletons includes a center skeleton enclosed in an oval. It holds a scythe in its right hand and scales in its left. Though imposing, the macabre decoration serves as a silent reminder of the brief passage of life on Earth and our mortality. Since 1851, the crypt was only open to the public for the week following All Souls Day. Then, in 2022, it stayed open all year round except for certain holidays.

Sedlec Ossuary, Kutná Hora, Czech Republic. Photo by Marcin Szala via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Beneath the Church of All Saints and a part of the former Sedlec Abbey is the Sedlec Ossuary in Kutna Hora, Czech Republic. The historic chapel initially belonged to the Cistercian abbey, founded in 1142 by Miroslav of Markvartic. Around 1400, a Gothic church was built with a vaulted upper level and a below-ground ossuary for the mass graves unearthed during construction. Between 1703 and 1710, a new entrance was added to support a failing front wall, preceding an upper chapel renovation.

In 1870, the Schwarzenberg family employed František Rint to organize the growing amount of bones. The effort achieved better harmony. About 40,000-70,000 disjoined human skeletons now form the ossuary’s grim but elaborate interior, which became one of the largest human bones collections among Europe’s bone churches. Other decorations include a chandelier with at least one piece from each type of human bone. Further, there are two large decorative chalices made of human bones, four Baroque bone candelabras, six enormous bone pyramids, two bone monstrances, the family crest of the House of Schwarzenberg, and skull candle holders. The chapel’s garlands of skulls draping the vault are unique. Rint even arranged his signature and the year 1870 with bones on the wall near the chapel’s entrance. Sedlec Ossuary was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995.

The Golden Chamber, Basilica of St. Ursula, Cologne, Germany. Photo by Vassil via Wikimedia Commons (CC0).

The Basilica church of Saint Ursula in Cologne, Germany, rose from the ancient ruins of a Roman cemetery. The nave and central tower of the Basilica were completed in the Romanesque tradition, while the choir was rebuilt in the Gothic style. The earliest evidence of a cult of the martyred Saint Ursula and her companions at Cologne dates to c. 400. The Golden Chamber (Goldene Kammer) holds the alleged remains of Saint Ursula, her 11,000 virgins, and many more. The remains are possibly from the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451, a battle led by the Visigothic King Theodoric I and Roman general Flavius Aetius against the Huns and their commander, Attila.

The exact number of people in the Golden Chamber and to whom the remains belong is unknown. The remains were found in 1106 in a mass grave seemingly disinterred during the construction of the Gothic church. Christine Quigley described the Golden Chamber as “a veritable tsunami of ribs, shoulder blades, and femurs” (Quigley, 2001) in Skulls and Skeletons: Human Bone Collections and Accumulations. The walls of the Golden Chamber are covered in bones arranged in designs and letters, along with relic skulls.

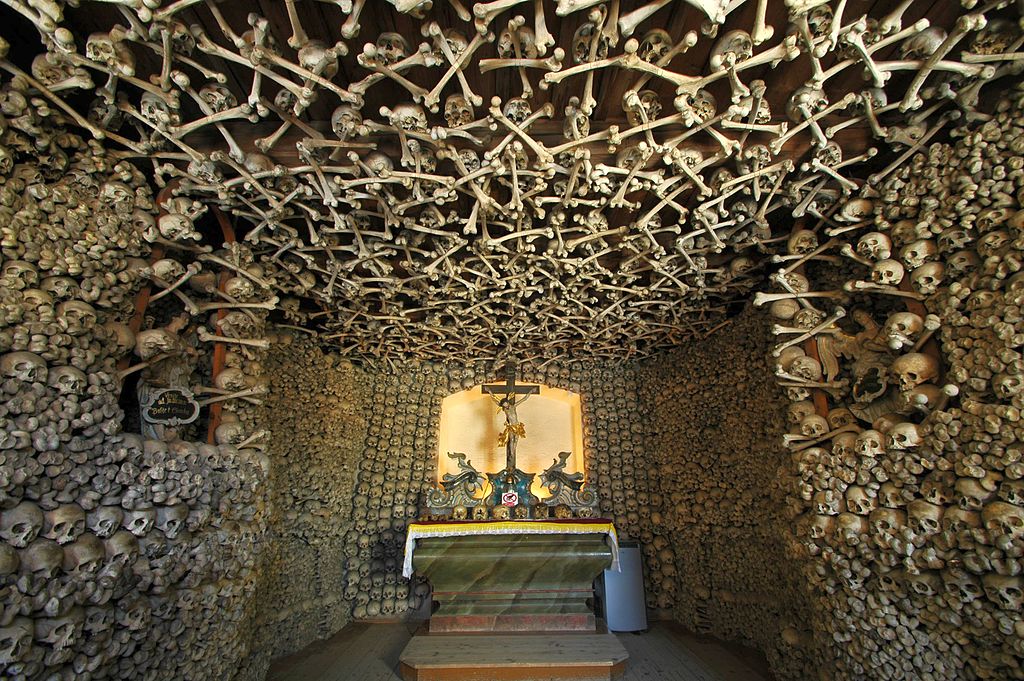

Václav Tomášek, Chapel of Skulls, Kudowa-Zdrój, Poland. Photo by Merlin via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0).

From the outside, the Skull Chapel (Kaplica Czaszek) or Saint Bartholomew’s Church is an unassuming Baroque church located in Kudowa-Zdroj, Poland. Inside, however, is a mass grave. With skeletal remains over its walls and ceiling almost connected to the floor, this chapel has perhaps more bone coverage than any others in Europe. Inspired by the Capuchin ossuary, local parish priest Václav Tomášek built it in 1776.

Václav Tomášek, Chapel of Skulls, Kudowa-Zdrój, Poland. Photo by Merlin via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0).

The structure served as a graveyard for those who died during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and the Silesian Wars (1740-1763) and for the victims of epidemics and starvation. Between 1776 and 1794, 3,000 skeletal remains were collected, cleaned, and placed in the chapel, with another 21,000 interred in the basement. Volunteers restored the chapel in 1945 after World War II. Since then, the site reappeared as a token of mortality, an admonition on the calamities of war.

Louis Hippolyte Lebas, Crypt of the Martyrs, Saint-Joseph-des-Carmes, Paris, France. Photo by Guilhem Vellut via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

The crypt of Saint-Joseph-des-Carmes in Paris, France, was a chapel for the convent of the mendicant order of the Shoeless Carmelites designed by Louis Hippolyte Lebas. The exterior drew from Neoclassical architecture and the interior from Baroque art and architecture. In 1613, Queen Regent Marie de Medici laid the church’s first stone, and the exterior was completed in 1620 before 14th-and 17th-century artworks were placed.

The Chapel of Saint Anne was the first to be completed, then filled with a dazzling arrangement of Baroque and Mannerist paintings, gilding, and sculpture. The Chapel of Saint Jacques is a lateral chapel along the nave nearly, where Baroque art and decoration prevail. The latter includes works by court painter Pieter van Mol and Peter Paul Rubens‘s student Abraham van Diepenbeeck. The Chapel of the Virgin keeps a marble statue of the Virgin Mary by Antonio Raggi, a student of Gian Lorenzo Bernini. It was a gift from Cardinal Antonio Barberini, brother to Pope Urban VIII.

Memorial in the Crypt of Saint Joseph des Carmes, Paris, France.

Though an artistic jewel in its own right, the church is directly associated with the September Massacres of 1792 during the French Revolution. Through September 2-4, 1792, George Danton ordered the execution of any individual who did not pledge to the French government. Nearly 1400 individuals, including 223 priests, were killed. Among those, 115 were killed at Saint-Joseph-des-Carmes by the sans-culottes, namely the militant partisans and advocates for abolishing the French monarchy, nobility, and Roman Catholic clergy.

The church thus became a prison before another mass execution of forty-nine aristocrats took place on July 23, 1794. In 1867, a burial site was discovered in trenches close to the church and showed casualties consistent with the accounts of the 1794 massacre. These remains were transferred to the church and placed in the Crypt of Martyrs in 1868. Consequently, the crypt also has remains from Jean-Marie du Lau d’Allemans, the Archbishop of Arles, along with two bishops, 127 priests, and fifty-six other individuals.

Shawn Tribe, “The Ossuary Chapel of San Bernardino Alle Ossa in Milan”, Liturgical Arts Journal. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

Stephanie Pappas, “The History Behind That Creepy Bone Chapel You Saw on Reddit”, Livescience.com, 2 Nov. 2017. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

Julia C. Fischer, Art in Rome, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 26 July 2019.

National Geographic, Sacred Places of a Lifetime, National Geographic Books, 2008.

“Church of St. Ursula”, Atlas Obscura. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

“Czermna’s Skull Chapel: The Fascinating Exhibit of 3000 Skulls and Countless Bones“, Ulukayin English, 18 Apr. 2023. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

“Eglise Saint-Joseph-Des-Carmes à Paris”, Patrimoine-Histoire.fr. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!