Early Life and Works

Oswaldo Guayasamín was born into a humble family in Quito, Ecuador on July 6, 1919, as the oldest of 10 siblings. His father was an indigenous Quechua man who worked as a tractor driver, while his mother was of mestizo (mixed) origins and stayed at home with the children. Her premature death during Guayasamín’s childhood would have a lasting impact on his life and, later, his art. Nonetheless, it was yet another tragedy in the boy’s early life which would put him on the path to becoming one of Ecuador’s most renowned painters and social critics. In 1932, the country’s second coup in two years was marked by four days of violence in Quito, during which a stray bullet hit and killed his closest friend.

As he had already been expelled from six different schools for what his teachers considered a lack of academic talent, he enrolled in the School of Fine Arts the following year against his father’s wishes. His first exhibition in 1942 stirred considerable controversy in the artistic community, as the majority of his works contained critical social and political undertones. Indeed, one of his first works, Los niños muertos, was dedicated to Guayasamín’s childhood friend who was killed in the conflict that took place when they were growing up.

Huacayñán

Following his graduation from the School of Fine Arts and the success of his first exhibition, Guayasamín traveled to the United States and Mexico, where he met the muralists Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, the latter of whom had become one of his greatest artistic idols. From Mexico he returned to South America, traveling through Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. The experiences he collected on this journey served as the inspiration for his first formal series, Huacayñán, which was realized mostly between 1946 and 1952 but also included works from his earlier days. The term “huacayñán” is an indigenous Quechua word which roughly translates to “trail of tears” and is used to describe a situation in which two people part knowing that they will never return to see each other again.

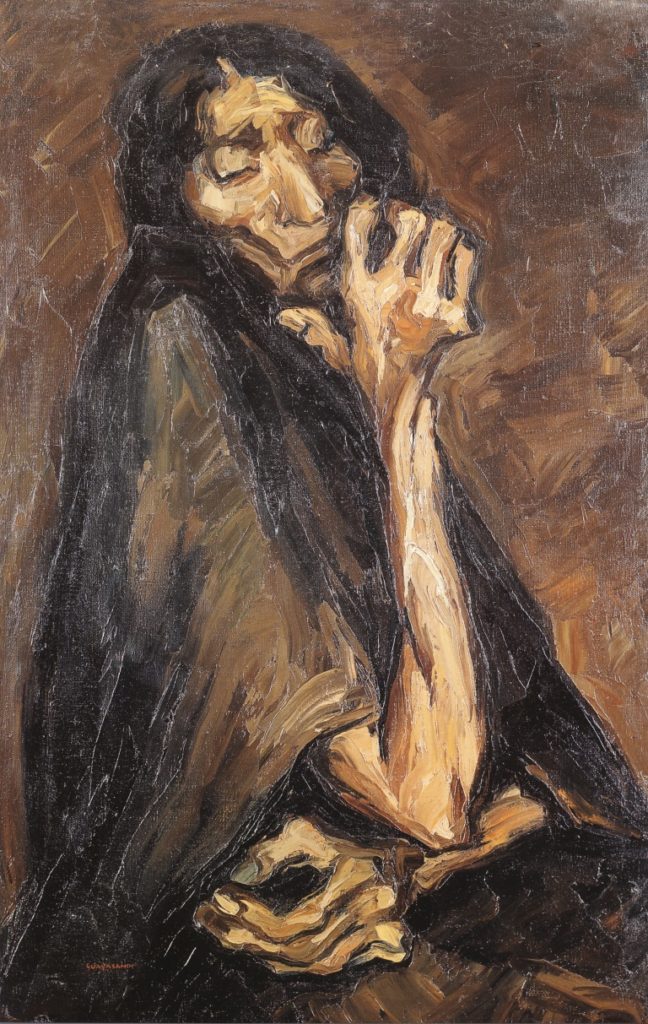

In the 103 works that make up the series, the artist developed an expressionist style with which he portrayed existentialist themes like the tragedy of life and human suffering. Accordingly, La vieja depicts an old woman of indigenous origin, lost in thought, her face revealing a worried and sorrowful state of mind. The series is also notable for Guayasamín’s incorporation of cubist influences into his body of work.

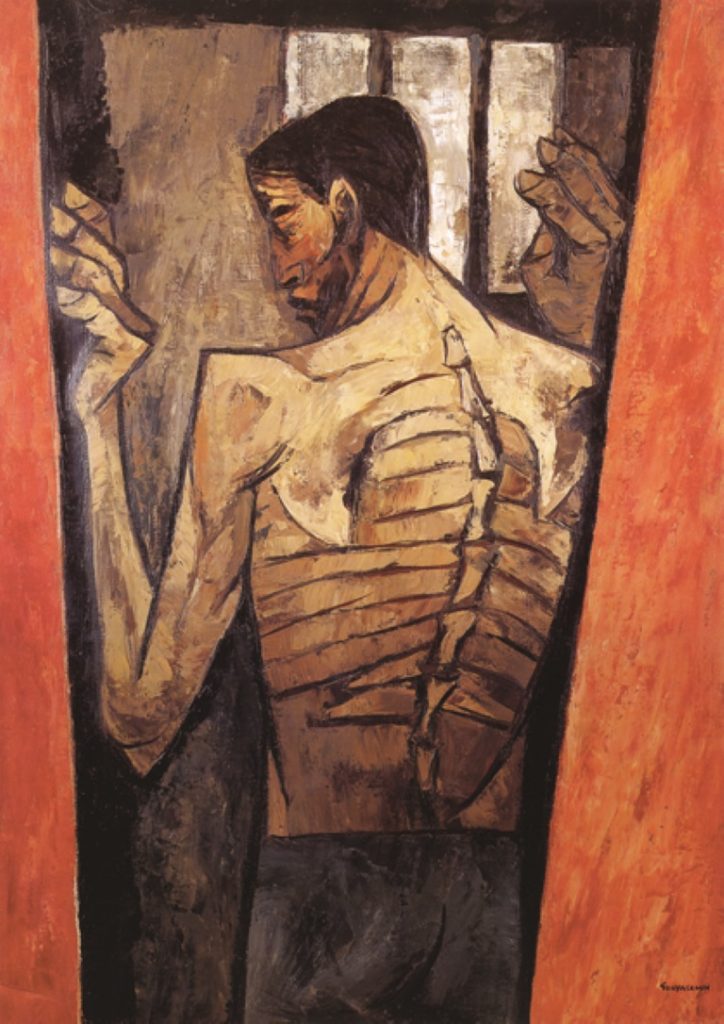

One of the first examples of such influences can be found in Prisionero, in which the slanted angles of the cell’s walls emphasize the cramped and claustrophobic nature of an indigenous prisoner’s everyday surroundings. Moreover, the sharp lines of his bony hands, shoulders, and back effectively capture his weakened physical condition.

The Age of Anger

After the completion of Huacayñán, Guayasamín began working on what would become the most expressive and politically-charged series of his artistic career. The arrival of the Cold War in South America was marked by the appearance of revolutionary movements throughout the region, accompanied by a wave of United States interventions aimed at eliminating communist presence from the Western Hemisphere. In South America, these interventions were carried out under the code name Operation Condor, a campaign orchestrated by the CIA with the purpose of implementing right-wing dictatorships wherever democracy failed to prevent the election of left-wing governments. The 1973 overthrow of Chile’s democratically-elected socialist president, Salvador Allende, by the CIA and his subsequent replacement with the totalitarian regime of Augusto Pinochet firmly solidified Guayasamín’s stance as a leftist and an anti-imperialist.

His work Lágrimas de sangre is dedicated to Allende and two other Chileans for whom the artist had a profound admiration: the theater director and musician Víctor Jara as well as Guayasamín’s close friend, the poet and diplomat Pablo Neruda. All three were killed in the 1973 coup.

The Age of Anger is characterized by less figurative representations of social issues than was his previous series, Huacayñán. Here, the artist’s primary focus shifts from portraying the struggles and injustices faced by indigenous people to expressing raw and universal human emotion. Additionally, he largely limits his palette to dark shades and cold blues. The gray he uses to depict the figures’ elongated hands, another characteristic element of the series, gives them a skeleton-like appearance. This color scheme and thematic focus are perhaps best manifested in the painting Manos de protesta, one of Guayasamín’s most iconic works.

The Age of Tenderness

Guayasamín’s third and final series marked a departure from the indignation of his previous periods. Between 1988 and his death on March 10, 1999, the artist painted over 100 works which he dedicated to his mother, whom he had lost in his early childhood. The Age of Tenderness makes frequent use of the melancholic blues incorporated into Guayasamín’s earlier works, but more vibrant colors are also used to represent the warmth conveyed when a mother embraces her child. Thus, the painting madre y niño serves as a prime example of the artist’s stylistic and thematic development in the latest stages of his career.

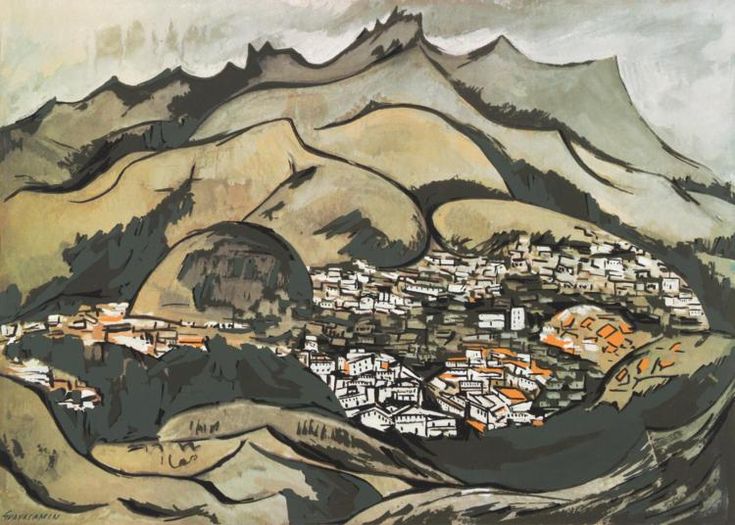

Apart from his three formal series, Guayasamín also produced a large collection of sculptures as well as still life and landscape paintings, the latter of which focused primarily on his hometown of Quito. Located at 2,850 meters above sea level, Quito is the world’s second-highest capital city (after La Paz, Bolivia) and offers spectacular views from the surrounding Andes Mountains. He also painted portraits for a diverse group of international figures, not least of whom were Fidel Castro and King Juan Carlos I of Spain.

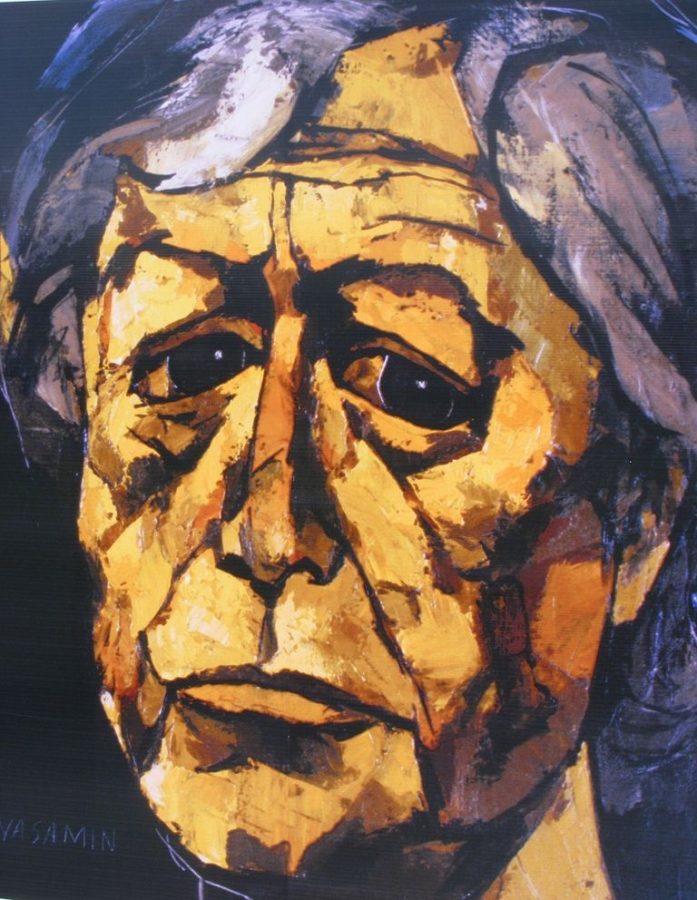

In his own Self-Portrait, completed just three years before his death, the artist made no attempts to hide the lifetime of hardship reflected in his worn and tired face. Today, the vast majority of Guayasamín’s works as well as donations from his personal collection can be found in Quito’s Guayasamín Foundation.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”8427805098″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/51hGOXxoyEL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”116″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”192088873X” locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/51T4PQTWlDL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”139″]