Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

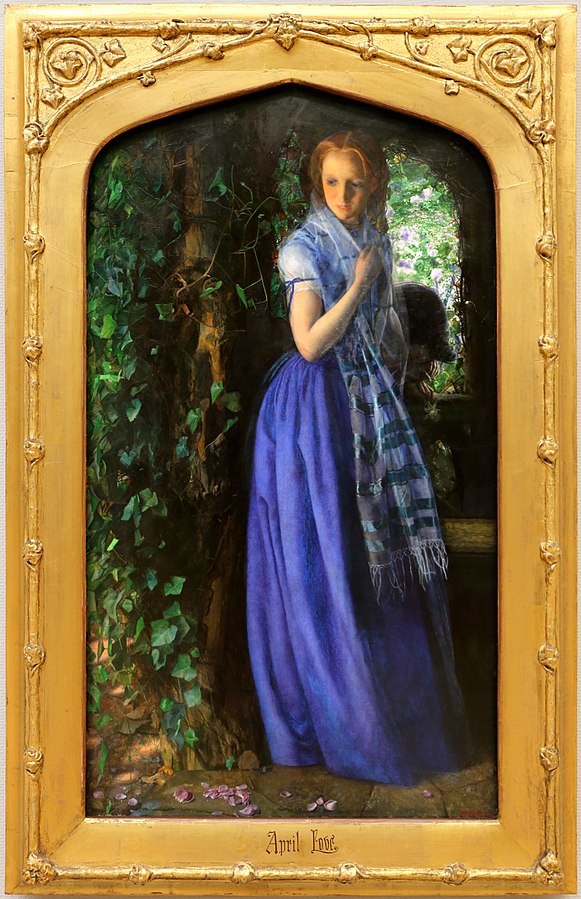

Today’s Masterpiece Story is about April Love – Arthur Hughes’ most celebrated artwork that perfectly embodies the Pre-Raphaelite soul.

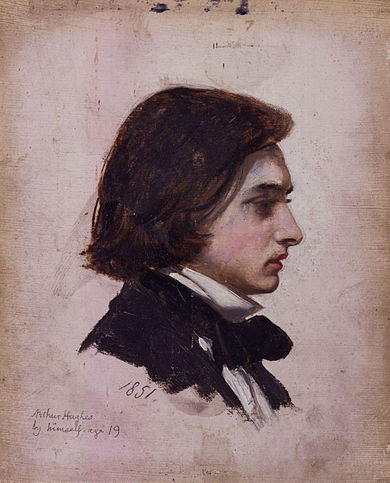

Although we consider April Love a Pre-Raphaelite painting today, the artist never actually joined the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as he was only 16 when the group was created. On the other hand, the interactions and dialogues he shared with its most important members led us to associate him with them.

The title of the painting, April Love, tells about its essence and meaning. Even if you didn’t know anything about the Pre-Raphaelites and their works, it would still be clear that what Hughes wanted to represent was one thing: love. But, here we are not just talking about how deep a person could feel for someone else; this painting is also driven by the painter’s devotion to poetry and symbolism, the themes every Pre-Raphaelite artist held dear.

April Love was first exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1856, and it was accompanied by an excerpt from Lord Alfred Tennyson’s 1842 poem The Miller’s Daughter:

Love is hurt with jar and fret,

Love is made a vague regret,

Eyes with idle tears are set,

Idle habit links us yet;

What is Love? For we forget.

Ah no, no.Alfred Lord Tennyson The Miller’s Daughter

Hughes didn’t want to make an illustration for the poem. He wanted the text to inspire the painting. For that reason, there were some changes to the poem’s images. For example, Hughes modified the setting of a millstream to include chestnut trees and forget-me-nots.

The artwork depicts a young lady in a purple dress and her lover hidden in the shadows. We instantly notice the contrast between the bright hues of the girl’s clothes and the darkness that renders the man less visible. They seem to be meeting in secret, as suggested by their hiding place under an ivy-covered arbor that looks long-forgotten.

Many clues suggest this is likely their last meeting: the juxtaposition of the lively lilacs, which symbolize young love, and the dried rose petals on the floor, representing the end of love and death. Also, if we look closer, we see that the man is holding a withered rose, which can be read as the lady’s lost virginity. But what confirms the breakup is the girl’s face. Her eyes are full of tears as she looks away from her lover.

John Ruskin, the leading art critic of that time, immediately grasped the power of the painting and described it as:

Exquisite in every way; lovely in color, most subtle in the quivering expression of the lips, and sweetness of the tender face, shaken, like a leaf by winds upon its dew, and hesitating back into peace.

The Works of John Ruskin, Ed. by Cook & Wedderburn, XIV, London 1904, p.68.

However, even though the painting tells a tale of young love and its inevitable end, there is another hidden story told by the soft, yet vivid colors: the look on the girl’s face and her body language, the dreamy and melancholy atmosphere—elements that proclaim the overwhelming tenderness and uniqueness of this love.

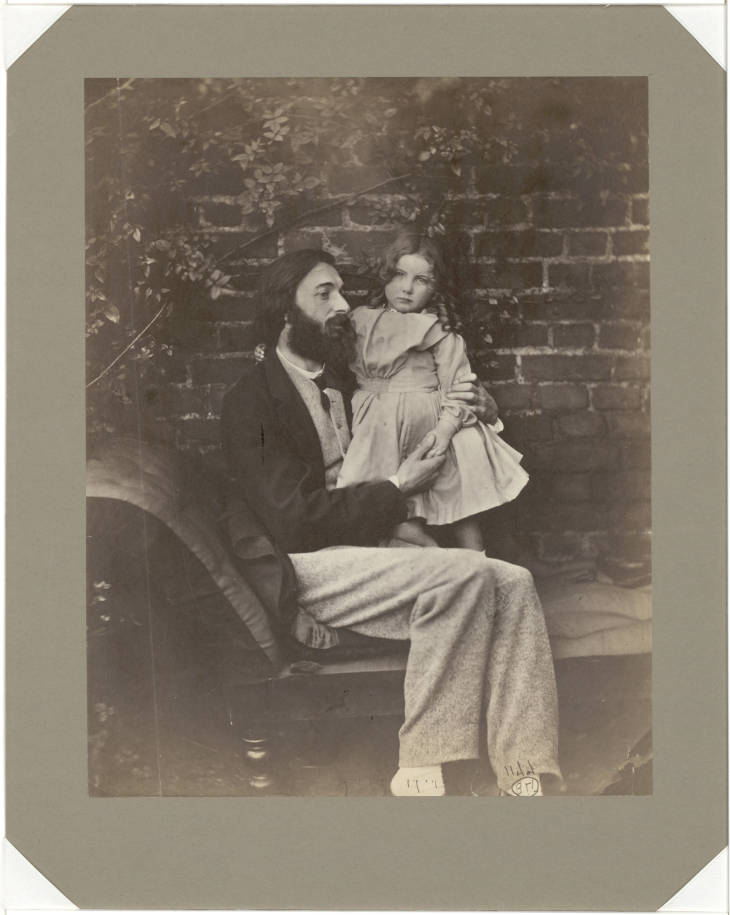

It might seem odd that Hughes decided to have his wife Tryphena Foord model for a painting that depicts the end of love. However, Foord posed for many of his works. Hughes also described her as his “early and only love.”

In most of these paintings, Tryphena Foord looks from unhappy to melancholic. Were their relationship on the rocks? Quite the contrary, they couldn’t have been happier: they were just married, had six children, and remained together for the rest of their lives. They were apparently luckier than any other Pre-Raphaelite couple; let’s just think about the hard and complicated relationship between Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!