Masterpiece Story: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash by Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is a masterpiece of pet images, Futurism, and early 20th-century Italian...

James W Singer, 23 February 2025

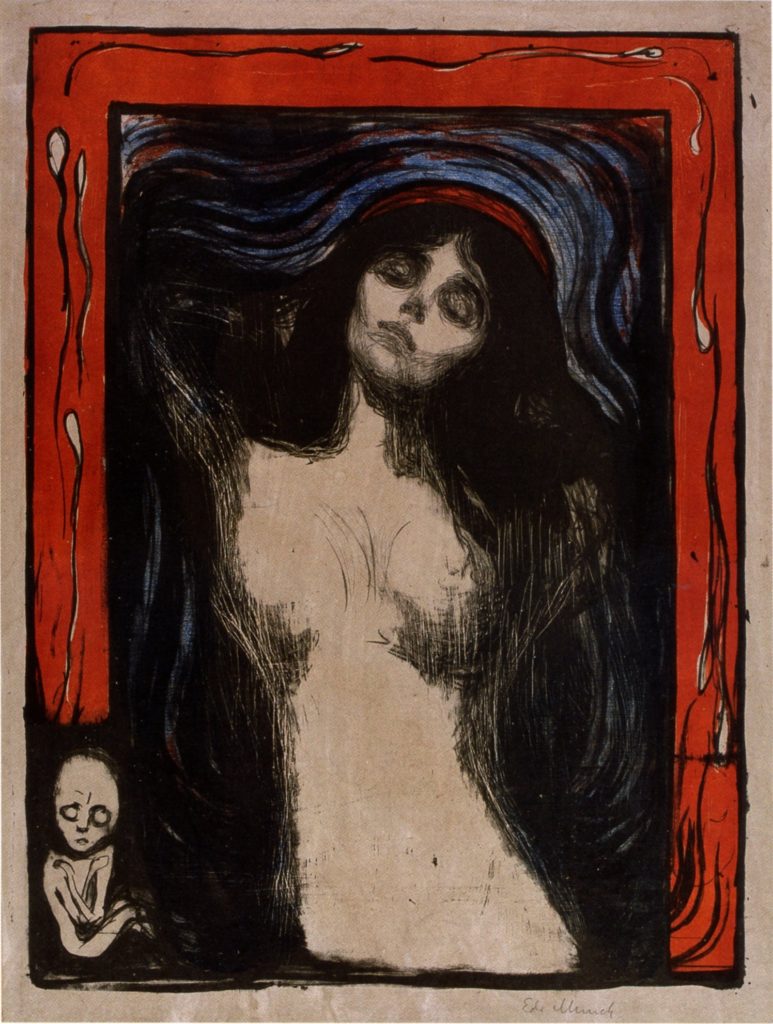

The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch realized the colored lithograph Madonna in 1895. He is considered the precursor of Expressionism, therefore his Madonna is imbued with its characteristics. Expressionism, born in the early 20th century, expresses a reality distorted by the subjectivity of the artist. The use of symbols, bright colors and marked features causes an emotional reaction in the spectator.

This Madonna gathers those characteristics. Edvard Munch strays from the traditional representations of the Virgin Mary and depicts her as a mystical woman. The multiples ambivalences on the painting show the complexity of her figure.

We can recognize this woman as Madonna thanks to a few details: the fetus that makes her a mother, and the blue halo around her head. Blue is the color traditionally associated with Madonna. Thick and curvy black lines overshadow this blue background. However, those lines let the blue appear on top of the woman’s head. As if only she could make it appear. She has a connection with the blue, it is part of her. Then, look at her belly, it is the only part of her body that is completely immaculate, a symbol of purity.

However, Munch paints this woman bare breasted, in a lascivious attitude. Her nudity echos her humanity. Indeed, it is very rare to cross path with a naked Madonna. In Christian religion (as many others) and its pictorial representation, the artists, whose art is often a command from the Church, always hide the female body.

On her face, with her eyes closed, we can see that she has abandoned herself to a wave of pleasure. The painter represents a woman in the act of love. Her position, facing the spectator, gives an impression of power coming from her. Through her posture she asserts her sexuality.

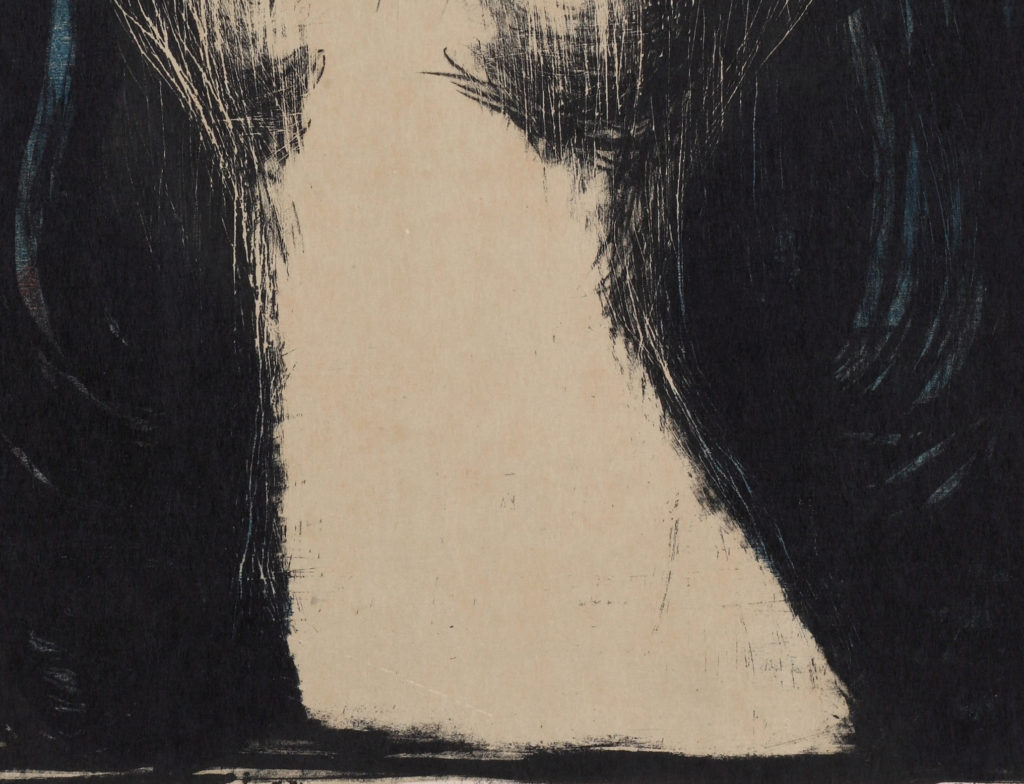

Her body, arms and hair merge into sinuous black lines that surround and cover the virginal blue. Those lines seem to possess each part of the woman except for her stomach, that is thus shown as pure. When I see the movement, the dynamic of the lines and the way they contour the body, I can’t help thinking about a sensual figure, which seems contradictory with the idea of purity given by her stomach and her name.

Therefore we can see a duality between divine purity and sensuality. However; the encounter of the two aspects in the portrait creates a sensation of fusion. Here, Munch insists on the polysemy of the figure of the Madonna which expresses itself through the encounter of life and death in the same character.

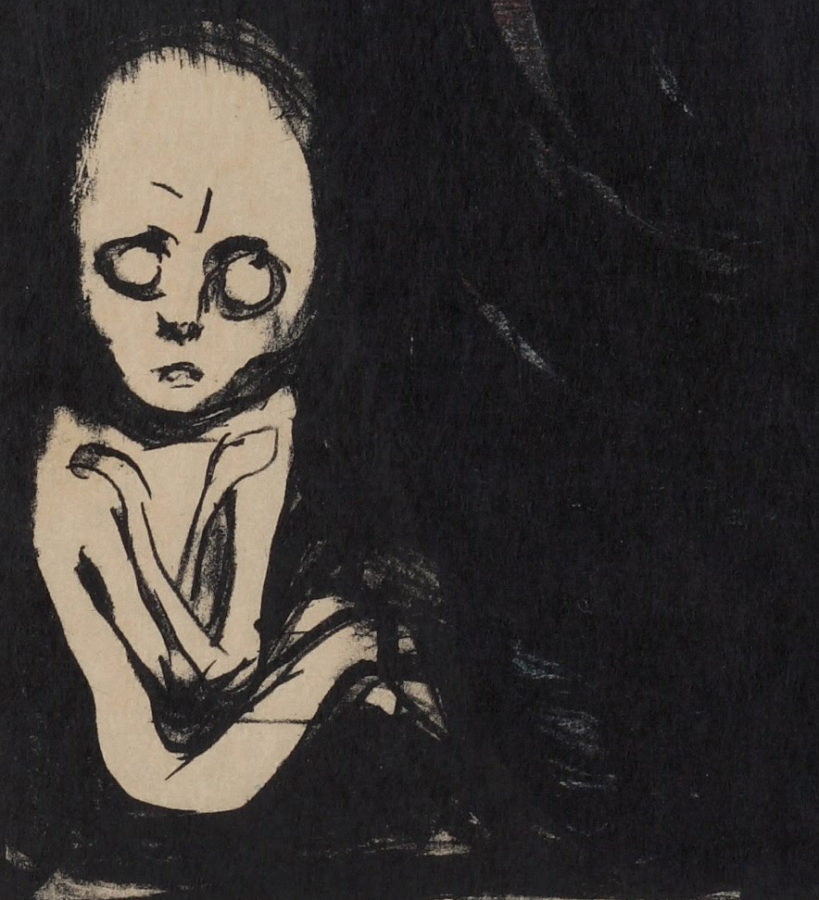

On the one hand, the Virgin Mary as a pregnant woman incarnates life. In the painting she carries a future baby. It is here where the fetus has a literal connection to its mother by the umbilical cordon.

On the other, she seems to extricate herself from the profound and tormented nothingness that is the background of the painting. She is able to do that thanks to the contrast between the whiteness of her stomach and the dark background. However, as I said, some parts of her body disappear in this darkness, as if she was sucked by it. Take a look at her hair and arms.

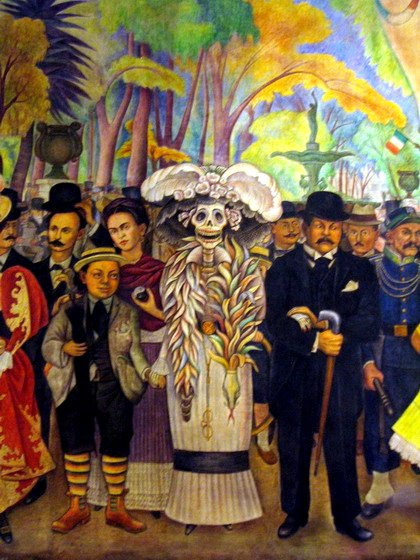

The shadows on her face, as the veil of death, is darker on her closed eyes and her hollowed cheeks. Her features are reminiscent of the “Calaveras” (Mexican masks for the Day of the Dead).

The look of the fetus stresses the presence of death. It is symbolically linked with life, a newborn to be. But, here it looks like a ghost, with arms crossed like the one of the dead. It creates a very creepy and heavy atmosphere.

Finally, those multiple ambivalences create a mystery but at the same time give a visual explanation to one of the great mystery of Christian religion: the creation of the Christ.

Symbolism had an important impact on Munch’s work. He used its codification to paint abstraction, giving it narrative aspects. In fact, symbolism plays with the invitation to decipher the mysteries in the painting and in subjects that are beyond comprehension.

Symbolism enables the painter to represent God, the maker of Christ. He is materialized through the spermatozoids heading to the Virgin’s stomach to fertilize her. The color of the background of the spermatozoids echos the Virgin’s halo, it underlines the relation between God and Madonna and confirms her divine aspect.

Finally, we have seen that thanks to the use of symbolism, Munch managed to give a narrative vision to a mystical scene. This mystic that is also part of Madonna makes her a very ambiguous character. The purity associated with her name contrasts with the apparent affirmation of her sexuality and the expression of a certain pleasure. She is human and she is divine, she flirts with Eros and with Thanatos.

Read about Munch’s relation to death here.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!