Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

19 March 2024 min Read

When you think of 19th-century Russia, images of Anna Karenina with black furs and white diamonds may come to mind. The lives of the wealthy aristocracy dominate the imagination with their excessiveness in everything: land, jewels, serfs, power, and wealth. However, there is more to 19th-century Russia than aristocratic diamonds, duels, and dukes.

There is the equally fascinating life of the merchant middle class. The middle class had its extravagances and ordeals especially when it came to matters of love, money, and prestige. Today we will explore The Major’s Marriage Proposal, a masterpiece from the little-known artist Pavel Fedotov, that discusses these themes that remain relevant today. Can love be successfully united with money and prestige? Let us explore this undervalued masterpiece to find out!

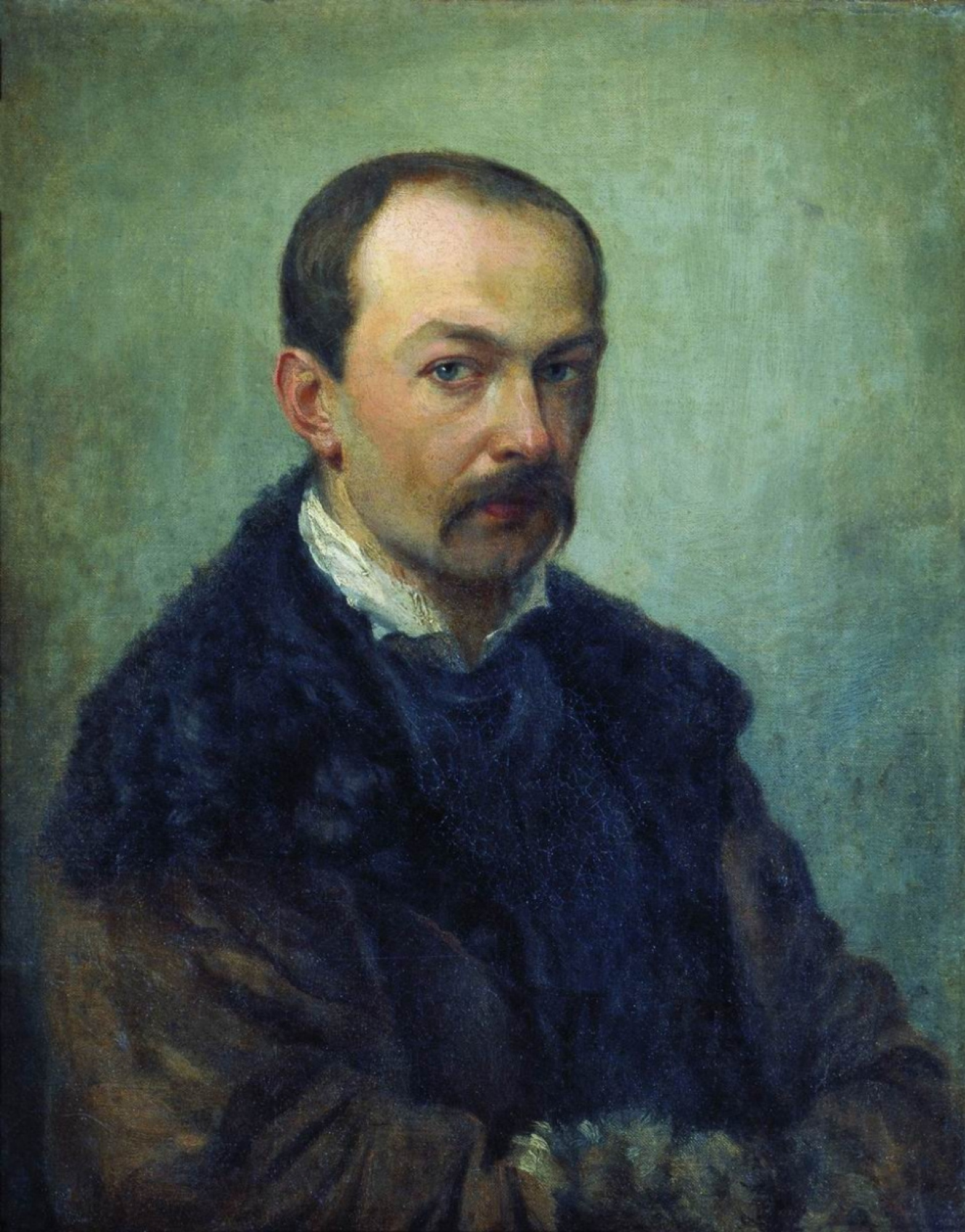

Pavel Fedotov was born in 1815 to impoverished Russian gentry. In 1826 at age 11, he attended the First Moscow Cadet Corps as a student learning to become a military officer. In 1834 at age 19, Fedotov was accepted into the Finnish Life Guards Regiment in St. Petersburg due to his excellent results in the military academy. After 10 years as an officer, in 1844 he decided to resign from his brilliant military career to pursue his dream as a successful artist. However, success as an artist continued to elude him throughout the remainder of his short life.

Fedotov only lived to the young age of 37 years when he died in late 1852. He died penniless, frustrated, and insane within the confines of a mental hospital. Friends and family continued to visit him during his short confinement. They remembered the brilliant officer who in the last 8 years as an artist had slowly gained artistic skills but slowly lost mental strength. It was cruel that someone so young with such a promising future should descend into madness and poverty. However, despite Pavel Fedotov’s tragic life, he did leave the world some of the most beautiful domestic interior scenes of the 19th century such as The Major’s Marriage Proposal from 1848.

When The Major’s Marriage Proposal was painted in 1848, Tzar Nicholas I had been ruling Russia for 23 years since his ascension in 1825. Nicholas I was the epitome of the reactionary ruler. He opposed the majority of political reform and social liberalization. Some historians describe him as being the perfect example of an autocratic ruler, or an absolute ruler. The ruling class had never been more firm in trying to maintain their status quo. They tried to reverse progressive measures made in earlier reigns and essentially viewed reforms as dangerous to the stability of society and political life.

The Russian art scene was strained under such an authoritative society. Sometimes artists had feelings and ideas that ran counter-culture to what Tzar Nicholas I mandated. The Tzar could control what the press printed but not what the people thought. Therefore, during this socio-political climate, new themes emerged in Russian art. Before the mid-19th century, Russian paintings typically depicted three subjects: historical events, Biblical stories, and aristocratic portraits. From the mid-19th century onwards more subjects were explored such as the middle-class. The middle class was emerging in Russia, as in the rest of Europe, as a powerful entity. They had more expendable income to spend on commodities including art. Therefore there was an emerging market for paintings depicting middle-class scenes. Fedotov explored the more interesting themes of love, money, and prestige. He did so in his The Major’s Marriage Proposal.

Pavel Fedotov painted The Major’s Marriage Proposal as a mise-en-scène, which is a theatrical French term meaning stage setting. Fedotov depicts the events of the painting as if they were a scene from a play. Everyone is posed and frozen into the most expressive gesture to heighten the storytelling of the scene. It is as if you were to freeze a film into the most dramatic frame and that frame encapsulates the entire film’s drama.

The Major’s Marriage Proposal depicts a very common experience in 19th-century Russia: an eligible bachelor seeking marriage with an eligible mademoiselle. The nobleman-major stands in the door frame to the far right of the scene. His body is illuminated from behind in a golden yellow light. His body is almost in silhouette, but all of his features including his bored face are visible. He does not project the gallant suitor of many people’s dreams, but the sensible and rational suitor of a sensible and rational marriage. While he does not exude love and affection, he does exude honor and respectability.

Pavel Fedotov then painted the matchmaker to the left of the nobleman-major. She wears a red frock with a dark skirt. Her hair is clad in a peasant’s scarf. She glances over to the father of the household. One hand holds a white handkerchief, while the other extends out and references the major behind her. She locks eyes with the father figure, and her mouth is open, suggesting she is saying something happy, positive, or encouraging. She is a good vendor, and she sells the benefits of the match between the major and the mademoiselle.

The father is clad in a dark and ill-fitting coat. It shrouds him in excessive fabric as it masks his body. He appears shapeless, and if it wasn’t for his white beard and ruddy complexion, he would almost blend into the background. He may be the head of this household but it is his wife and daughter that steal the scene. The father is a successful merchant. His enviable income is reflected in the richly decorated room. The ceiling is paneled and painted, the floor has inlay marquetry, and the room features beautifully crafted objects such as a chandelier, gilt picture frames, and fine glassware. There is an opulence of middle-class prosperity, and he has a house and family with aspirations of good taste.

To the left of the father is the elegantly dressed mother. She wears a dusty pink dress with a white shawl. A diamond earring dangles and sways as she abruptly turns her head towards her daughter. The mother’s hair is wrapped in sea-foam green scarf in a similar style to the matchmaker. While the mother has aspirations of middle-class gentility through her clothing and jewelry, she is exposing her peasantry origins with the headscarf and crude gesture. Women of more elevated taste did not wear headscarves in Russia. Instead, they wore jewelry pieces in their hair, or nothing at all. The mother holds her shawl in one hand, and tugs uncouthly on the pearl white dress of her daughter. She appears to be restraining her daughter from running away. The mother’s lips are open and her eyes wide as if she is ordering, “Come back here, child!”

In the left-centre of the painting is the focus of The Major’s Marriage Proposal. The daughter is a vision of loveliness. Her cream dress has many layers and flounces around her legs. It has the look of a wedding dress which based upon the painting’s title seems appropriate. The daughter’s dress implies she is a virginal woman with a sizable dowry. Her alabaster shoulders and neck are exposed showcasing a beautiful necklace of three strands of pearls. Matching earrings complement the ensemble.

The daughter is attempting to flee the room to the left as the major stands on the right. Just like a mise-en-scène, characters enter and leave according to the scene’s drama. The daughter’s attempted flight speaks volumes. Two interpretations have been presented by art historians. The first is due to modesty as respectable unmarried women did not reveal so much neckline. If the dress was revealing, then a shawl was wrapped over the shoulders. The daughter is fleeing because she does not want her suitor to see her so immodestly dressed. This interpretation seems silly because the daughter has a lacy shawl around her elbows. Why wouldn’t she simply cover her bare shoulders and not flee? No, the second interpretation makes more sense, and it is that she does want to marry her suitor. She is not in love with him.

The Major’s Marriage Proposal is a painting about a mariage à la mode or a fashionable wedding where the two parties are exchanging more than just vows. The most typical exchange is the groom offering a title, and the bride offering a generous dowry. Money is exchanged for status through marriage.

Exploring the theme of mariage à la mode has been depicted by other artists like Jean-Honoré Fragonard, William Hogarth, Sir William Orchardson, etc. Pavel Fedotov was neither the first nor the last artist to explore this satirical theme, but he explored it very well. He “teach[es] morals by means of a beautiful spectacle.” More research should be done into the life of Pavel Fedotov, especially in producing works like The Major’s Marriage Proposal. The brevity of his life prevented an extensive collection of works, and that is probably why he never rose to the international fame he aspired to during his lifetime. The Major’s Marriage Proposal has great visual complexity, storytelling, and drama. It explores the themes of love, money, and prestige. This is a Russian mise-en-scène.

Victoria Charles, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal. 1000 Paintings of Genius. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2006.

Eugene Ehrlich. Les Bons Mots. New York, NY: Henry Holt & Co., LLC., 1998.

“Fedotov Pavel Andreevich.” State Tretyakov Gallery. Accessed March 29, 2020.

“The Major’s Marriage Proposal.” State Tretyakov Gallery. Accessed March 29, 2020.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!