12 Best Shots of the World Press Photo 2024 Exhibition

The World Press Photo Exhibition is a renowned annual event showcasing some of the most impactful visual photojournalism from across the globe.

Nikolina Konjevod 10 February 2025

Paris is a centuries-old city which witnessed many ground-breaking moments. One of them was the first photograph of a living human being ever taken! Inspired by this, I’ll take you on a journey back in time to when the exposure time for a photo took around 10 minutes. Here is Paris in early photographs.

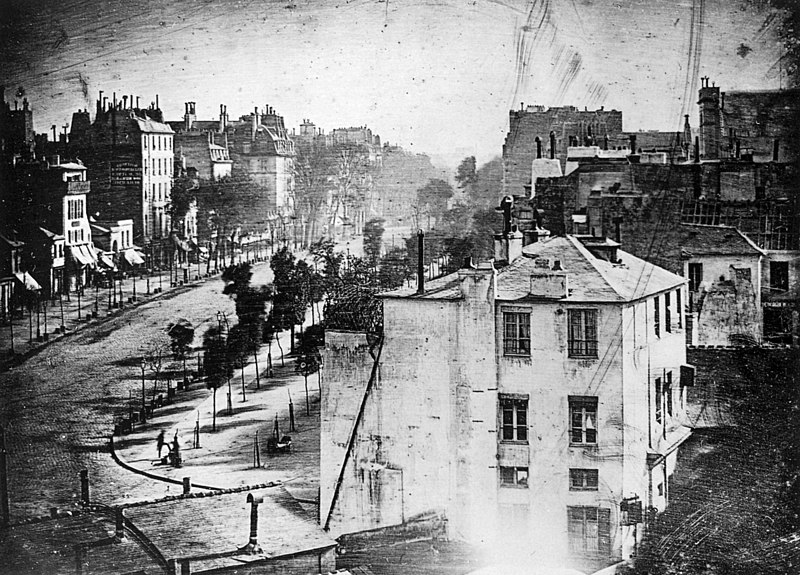

According to research, the first photograph depicting people was a daguerreotype of the Boulevard du Temple (at the time known as Crime Boulevard because theaters in the area were famous for showcasing murder mystery plays). In the beginning of the history of photography, early photographers found it difficult to capture any people. This is because the exposure time for successful photographs took several minutes and people usually move, even unintentionally. Here, however, in the lower left corner, we see two silhouettes of men. One is having his shoes polished and the other one, a little blurred, is a shoeshine boy. The man must have stayed immobile for at least a couple of minutes to be so visible in the photograph. This subsequently gained him the title of the first man ever captured in a photo. It’s worthwhile to stay still sometimes, keep it in mind guys!

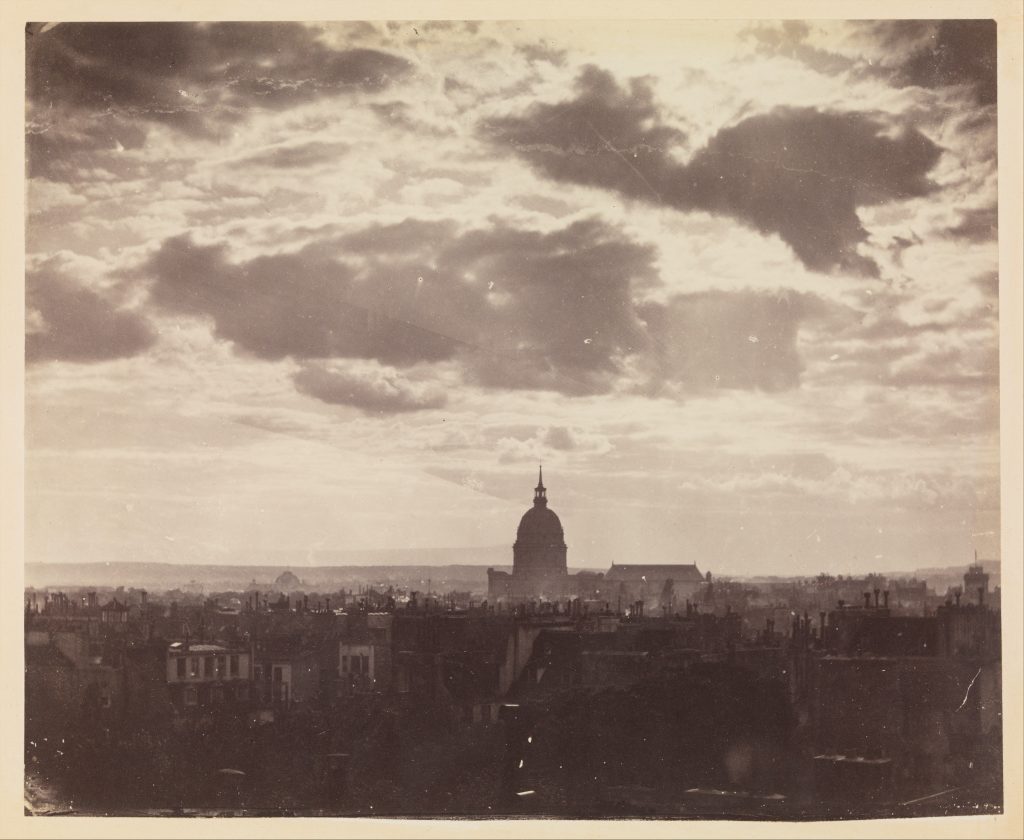

Haussmannization is a term used to describe the project of dramatic and drastic change to the urban fabric of Paris. It took place during the reign of Napoleon III, under the supervision of Georges-Eugene Haussmann. Haussmannization intended to renovate the run-down city whose medieval structure was too old and therefore insufficient to satisfy the needs of modern inhabitants. Grand in design, the changes negatively affected the poorest members of Parisian society; houses were often torn down and families relocated far from the city center.

Nevertheless, the project guaranteed better air circulation in the city, improved the sewage system, and made Paris the ‘City of Lights’, as twenty thousand gas lamps were installed in the streets. Moreover, Baron Haussmann installed tens of thousands of pieces of street furniture including benches, kiosks, Morris columns (for posting advertisements), pissoirs, and garden gates. In order to document this enormous urban transformation, the city of Paris commissioned Charles Marville (1813–1879) to photograph the neighborhoods that were about to fall into oblivion and the ones that were about to shine in new light.

We are used to seeing photographs as history, as evidence of the past. Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida, eloquently described the perception of a photograph as a kind of death, a stop-time that flows not forward but ‘back from presentation to retention.’ Yet this early period of French photography makes manifest another layer of complexity, of temporal and spatial reality, that cannot be adequately explained by this formula. The image makers describing Paris during the mid-19th century were, like Haussmann, forging a new visual image of the city parallel to the prefect’s own; whether working on commission or on their own, they too were shaping urban space, in two dimensions as opposed to three. And interestingly enough, these new visions, as if possessed of a certain clairvoyance, appeared years before the construction crews arrived, making these pictures a sort of magic mirror through which the then Parisian future can be dimly perceived.

Shelley Rice, Parisian Views. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Called ‘the eye of Paris’, Brassai was not a Frenchman by birth. He came from Brassó, Transylvania (in modern-day Romania). He came to Paris in 1924 after fighting in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I and studying art at Berlin-Charlottenburg’s Academy of Fine Arts. In 1932 he decided to change his given name, Gyula Halász, to Brassaï, which reminded him of his birth city. As a journalist, he quickly met the crème de la crème of the Parisian artistic milieu, getting to know people like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and the Surrealists. His photograph of the view from Notre-Dame is one of the most iconic Parisian photos ever taken.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!