Summary

- The Paris Salon had a history of over 200 years.

- During that time, political changes directly affected the Salon.

- Women had reduced but significant participation that increased through the years.

- In the last third of the 19th century, various alternatives appeared that challenged the Salon.

- At the beginning of the 20th century, the Salon had lost its relevance.

A New Idea of the Artist

During the 17th century, the old gremial system was declining. With the Enlightenment and its rationalist ideas came a different style of artistic training. Before, anyone who wished to become a painter had to enter a master’s workshop and work their way upwards. Once they had learned everything they needed they could open their own establishment and train the next generation. But in 1648, the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture was founded with the support of Louis XIV. One of the main promoters was Charles le Brun after a trip to Italy. He took the Academy of Saint Luke in Rome as a model. As such, students entered at a young age, learned from multiple teachers, followed a strict curriculum, and graduated.

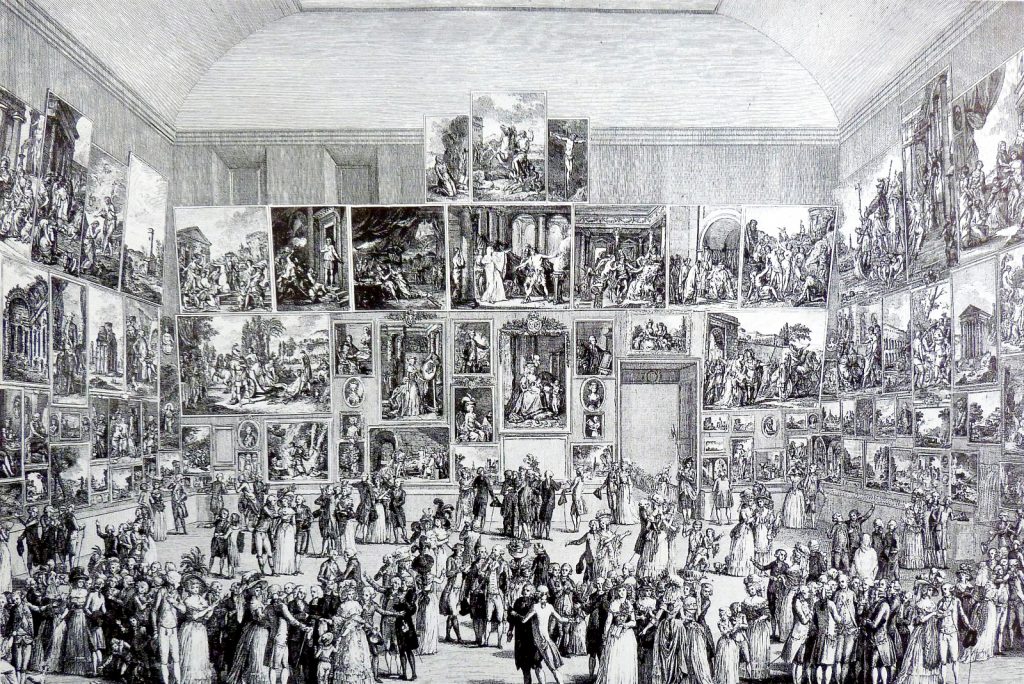

The Paris Salon of 1787, 1787. Le Salon du Monde.

Nicolas de Largilliere, Charles Le Brun, 1683-1686, Musée de Louvre, Paris, France.

Like that, the artist became a learned man, one who studied, created, and taught beauty and taste. Furthermore, it aimed at distinguishing artists from artisans. As such, there was a series of principles that dictated the Academy. For instance, there was a preference for classical and biblical elements. Consequently, historical painting took a prominent place in the hierarchy of genres. Furthermore, there was the importance of the human figure and drawing from life. In this new context, the Salon was born to exhibit the works of the members of the French Academy. Apparently, they had the duty of showing their works on Saint Louis’ Day: August 21st. Although, they did not always respect that.

Jean-Baptiste Martin, A meeting of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture at the Louvre Palace, 1712-1721, Musée de Louvre, Paris, France.

The First Paris Salon

In April 1667, the first exhibition took place in the Palais Brion in the Palais-Royal. Unfortunately, very little information has survived. There is no list of works or artists that participated. However, Jean Rou left his testimony about his visit. According to him, all sorts of people of all ages attended.

One cannot say what a pleasant sight it was for me to see all at once such a prodigious quantity of all sorts of works in all the different parts of painting, I mean history, portraiture, landscape, the seas, the flowers, the fruits; and by what kind of magic, as if I had been transported to foreign climes and to quite remote centuries, I found myself a spectator of these famous events whose surprising stories had so often filled me with admiration.

The Livrets

Afterward, the Academy continued organizing these events on a rather irregular schedule. Finally, in 1673 the first catalog (livret) appeared. It listed the paintings and sculptures in the exhibition. The little booklet described each painting shortly. For example, Charles le Brun had a series of four canvases about the life of Alexander the Great. Other artists include Henri Testelin, René Antoine Houasse, and Madeleine Boullogne. Not until the 1880s would there be illustrated ones.

Charles Le Brun, Entry of Alexander into Babylon or The triumph of Alexander, 1665, Musée de Louvre, Paris, France.

The Salon Finds A New Home

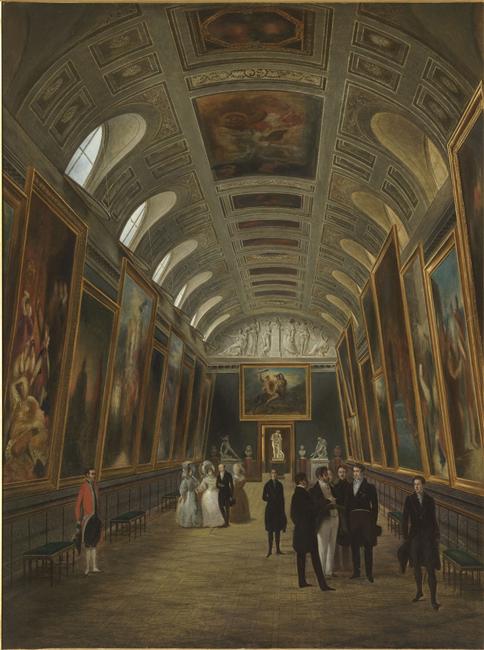

In 1725, the Paris Salon moved to the Musée de Louvre. There, one could already view the antique collection. It was also a place for education as it allowed students to copy the works. Consequently, the exhibition took place at the Salon de Carré. From there, it acquired the name “Salon”. In truth, the exposition of antique and contemporary works in the same place seemed very attractive. And especially in a time where Western art looked at that past as a model and source of inspiration. After the defeat of Napoleon and the reestablishment of the republic, the link between the museum and the salon tightened. Yet, this was not welcomed by everyone. As a matter of fact, there were opponents who complained about the prominence of contemporary pieces. They felt those works obscured the antique ones. Finally, in 1848 they got their wish and the Louvre stopped hosting.

Gabriel-Jacques de Saint-Aubin, View of the Salon of 1765, 1765, Musée de Louvre, Paris, France.

But the Paris Salon was a temporal installment. Therefore, in 1818 the Museum of Luxembourg opened to permanently exhibit the works at the Salon. It was the first museum dedicated to living artists. With this, the French government was able to exhibit French pieces after they had restituted the art spoiled during the Napoleonic wars. Notably, the paintings remained there during the artist’s lifetime. When they died, they were transferred to the Louvre.

Auguste Jean Simon Roux, Louis-Philippe and Marie-Amélie visiting the Museum of Luxembourg in 1838, c. 1848, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

Art Criticism at the Paris Salon

The Paris Salon was a place of contemplation, but also of conversation. Inevitably, the public became the judges too. In consequence, a new branch of art appeared: art criticism. In the 1740s, anonymous critics appeared in magazines, books, and pamphlets. Actually, many of them did not have artistic instruction. Plus, they could receive payment. However, with time, even the greatest thinkers like Diderot contributed to the discussion.

Historical Salons

An institution of more than 200 years saw quite important events happening right inside it. Moreover, the political, economic, and social changes in the city directly affected the Salon. Here are some examples from historic salons:

Prizes at the Paris Salon

Because being accepted into the Salon was not enough to honor a good artist, the Academy awarded medals to the best of the best. Of course, the artist who obtained it became highly valuable during that year. It made it increasingly probable that the State or another wealthy patron would buy his work. Additionally, he guaranteed his place at the Salon from then on. Furthermore, the medal came with a significant amount of money.

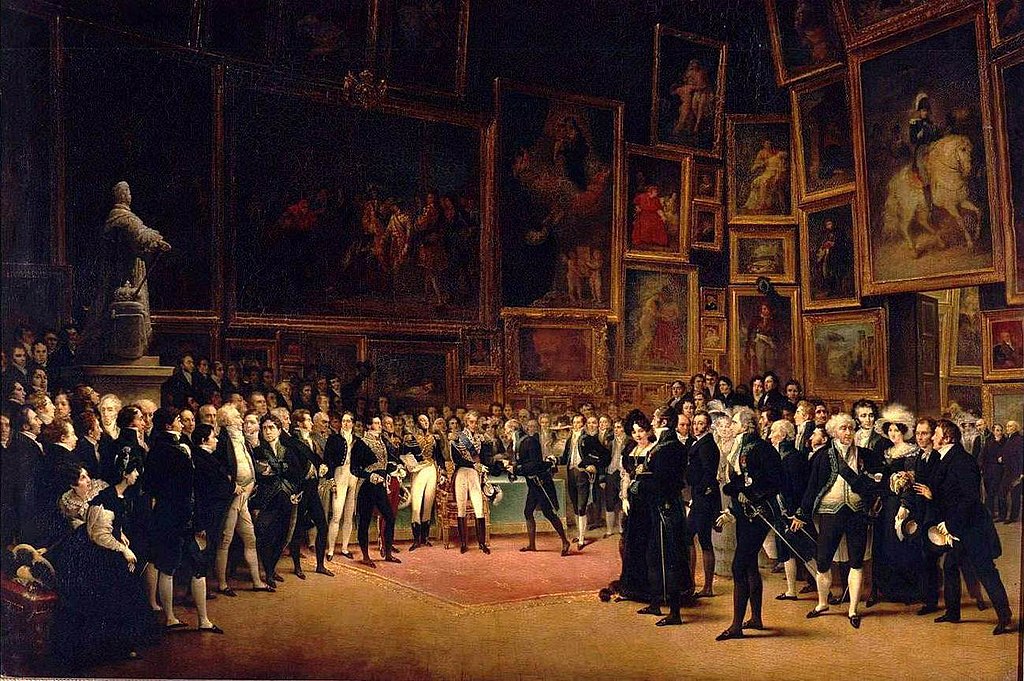

François Joseph Heim, Charles V Distributing Awards to the Artists at the Close of the Salon of 1824, 1824, Musée de Louvre, Paris, France.

In 1849, a jury became responsible for the awarding of medals and prizes. Some of the members were Delacroix, Ingres, and Corot. One of the first winners was sculptor Jules Cavalier for his Penelope. Additionally, titles such as “honorable mention” and “medal status maintained” appeared in the 19th century. All of these were encouragement efforts to ensure excellence at the Salon.

Left: Jules Cavalier, Penelope, 1849, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Right: Albert Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, Between two lovers, 1867, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Enduring Changes

The Paris Salon accepted quite a few changes throughout its history. Here, we are talking about stylistic changes that caused discussion at first but ended up being accepted. For instance, Jacques Louis David was a source of discussion among critics. First, his Neoclassical style was a radical change from the Rococo works the French society was used to seeing. Moreover, it came with a new set of values closely linked with the revolutionaries. Of course, his political standing made him a controversial figure. In any case, his paintings hung at the Salon on several occasions.

Jacques-Louis David, The Loves of Paris and Helen, 1789, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, France.

A Bazaar

Another aspect in which the Salon evolved was in the variety of genres. At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, the jury began accepting more genre paintings. However, most traditional critics saw it with negative eyes. With the hierarchy of genres that existed, the descriptive ones, such as portrait, landscape, still life, and genre scenes were not appreciated enough. Yet, due to its smaller size, it was easier for artists to produce many of them yearly. In fact, these last ones were developed in Northern Europe which was also the center of the art market in the 17th century.

Jan Frans van Dael, Flowers and fruits, 1810, Musée de Louvre, Paris, France.

Moreover, these pieces became attractive to art dealers from the middle class. Consequently, conservatives criticized the Salon as they felt it had become a bazaar. They also lamented the lack of History painting and the transformation of painting into “industrial products”. However, as the years went by, the Salon became essential in the art market.

The Paris Salon Grows

What started as a national or even local Parisian event quickly transformed into a Western phenomenon. Artists from all over Europe and the United States tried their luck every year. The number of works submitted grew yearly. It got so big that by the 1830s, the voices asking for a change of place increased too. Among the criticism of its Louvre location, there was the matter of lack of space. Actually, the famous arrangement from floor to ceiling was a question of space more than anything else.

Everything revolves around this Salon: the satisfaction of pride, reputation, fame, fortune and the guarantee of bread and butter.

Tabarant A. (1963: 12), La vie artistique au temps de Baudelaire. Cited in Hélène Delacour and Bernard Leca, “The decline and fall of the Paris Salon: a Study of the Deinstitutionalization Process of a Field Configuring Event in the Cultural Activities”. 2011.

This quote from Baudelaire is one of many that reflect the tremendous importance the Salon had at that time. Tragically, this cost the life of Jules Holzapffel as he died of suicide after a rejection in 1866. Truly, it shows the amount of pressure that everyone suffered at the time. Rejections gravely affected an artist’s career.

Road to the Salon

Everything around the Salon was a big deal. As such, even the day of the reception turned into a special event. May Alcott Nieriker wrote to her family about it to her family.

We live in exciting times, for on Saturday the great rush began towards the great Palais de l’Industrie, and pictures appeared in every direction: enormous nudes elegantly framed, small sketches, water-colors carried by the ladies themselves, immense furniture wagons packed tight stood in lines before the great entrance. This state of things continues for three days.

Caroline Ticknor, May Alcott. A memoir, 1928.

Afterward, the participants had to wait six weeks for the jury to make a decision. The fortunate ones were allowed the artist to enter the exhibition and apply the last touches a day before the opening. It was called vernissage or varnishing.

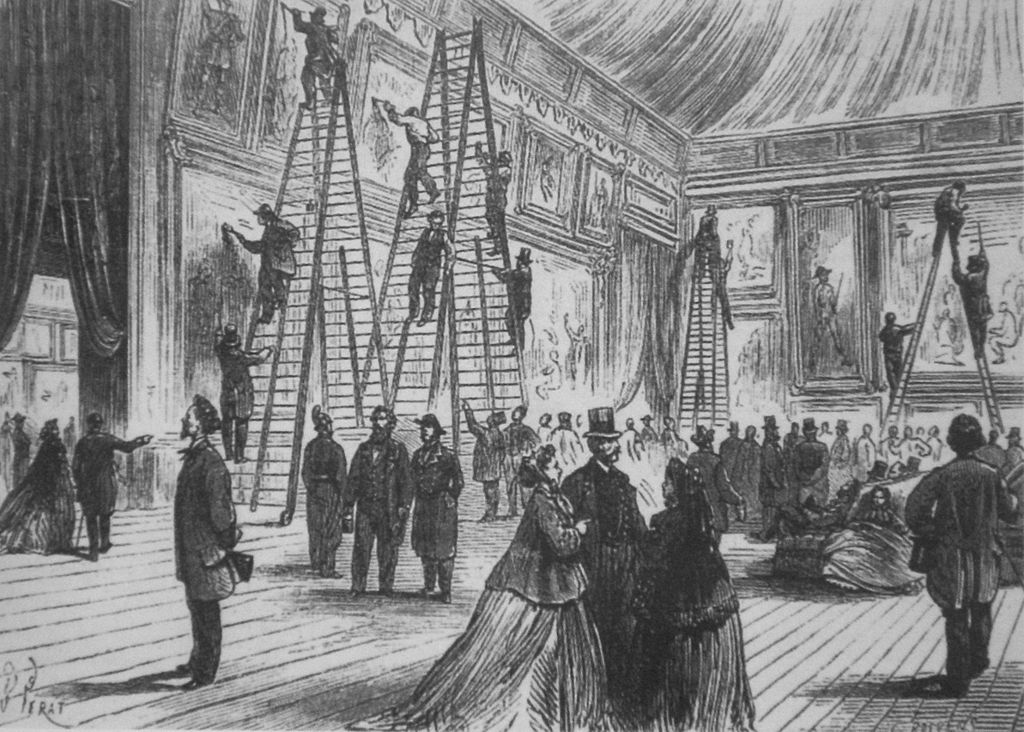

B. Perat, Varnishing at the Salon, 1866. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Women at the Paris Salon

Not surprisingly, the presence of female artists at the Salon was significantly minor compared to their male fellows. Nevertheless, there are records of quite a number of women who got in from the beginning. One of the first must have been the Baroque painter Madeleine Boullogne in 1673. Actually, she was the daughter of one of the founders of the Academy, Louis Boullogne. Therefore, her parentage most likely facilitated her entrance at the institution, along with her sister Geneviève. She focused on still lifes and exhibited again in 1704.

Madeleine Boullogne, Trophies of War, ca. 1672, Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

Like Boullogne, it was common for women to focus on still lifes, genre painting, and portraiture. This was because they were not allowed to enter the nude sessions. As a result, they lacked the anatomical knowledge necessary for history painting. Nonetheless, some of them could always find a way to go beyond. In this case, Marie-Guillemine Benoist became the first woman to exhibit a history painting in 1791. Though her artistic career ended shortly after, her achievement at the Salon is remarkable.

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Psyche Bidding Her Family Farewell, 1791, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

During the 19th century, the number of female artists increased considerably. They also received prizes. For example, Elizabeth Gardner Bouguereau became the first American female artist to get into the Salon in 1868. Almost twenty years later, she won a medal for The Farmer’s Daughter.

Elizabeth Gardner Bouguereau, The Farmer’s Daughter, 1887. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Artistic Differences

For more than 150 years, the Paris Salon enjoyed a monopoly on art exhibitions. While there were a few attempts at competing, they never succeeded. However, in the last quarter of the 19th century, several new options began to appear on the scene. The rigidness of the Salon and its increasing rejections cause discontent among the artists with innovative tendencies. As a result, those who were rejected took matters into their hands.

Le Salon de Refusés (1863)

In 1863, a record number of rejections caused problems for the Salon. From the more than 5,000 works submitted, the jury only admitted 2,000. Seeing this, Napoleon III created the Salon des Refusés in the Palace of Industry. Curiously then, the works at this salon were not exactly against tradition. By then, the Salon had serious problems with accommodation. Nevertheless, there are those who clearly deviate from the Academic standards. One of the most important artworks was Édouard Manet’s scandalous The Luncheon on the Grass. While the Academy accepted nude paintings, they tend to represent mythological or allegorical images. But an everyday woman sitting naked with a group of men was too much for the conservative jury.

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

The Impressionist Exhibition (1874-1886)

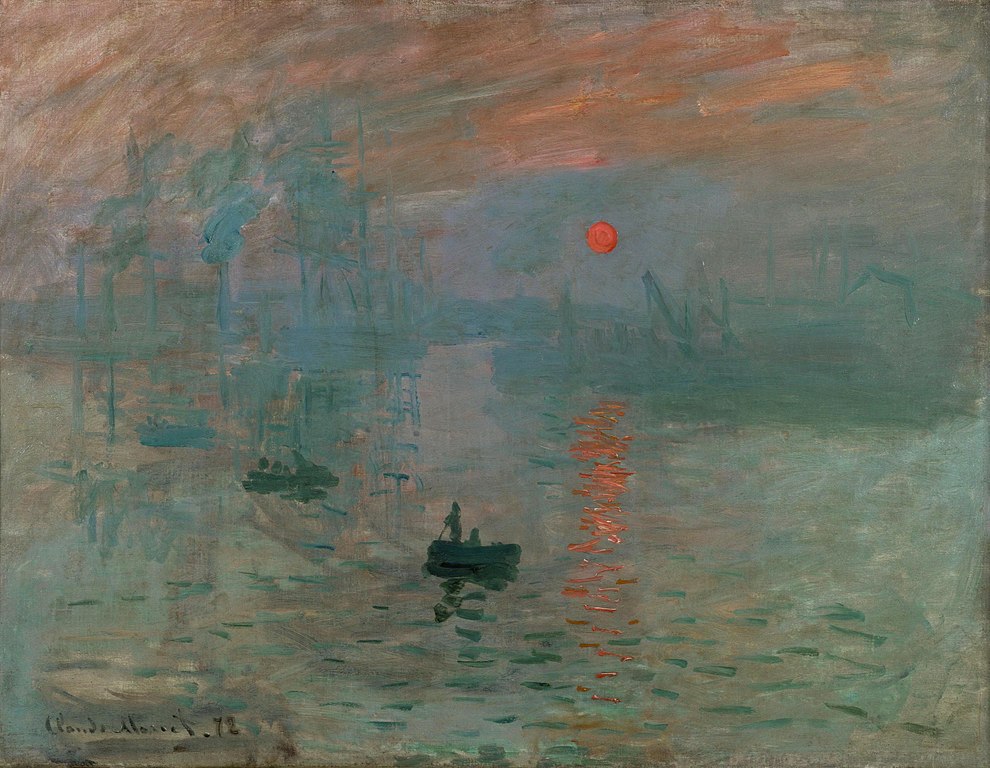

Then, after years of rejections, the Impressionists got tired of the Academy and its Salon. So, they decided to open their own exhibition. They curated their works themselves in the studio of Nadar, a French photographer. Moreover, it is in that first exhibition in 1874 that Monet’s Impression, Sunrise gave the name to the group. Really, the critic who called them “Impressionists” meant no compliment, but the artists took it anyway. A few of them like Pierre August Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and Mary Cassatt kept trying at the official salon for a few years. While they did not achieve the same visibility by far, at least they could show their works freely.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France.

The Salon of Independents (1884)

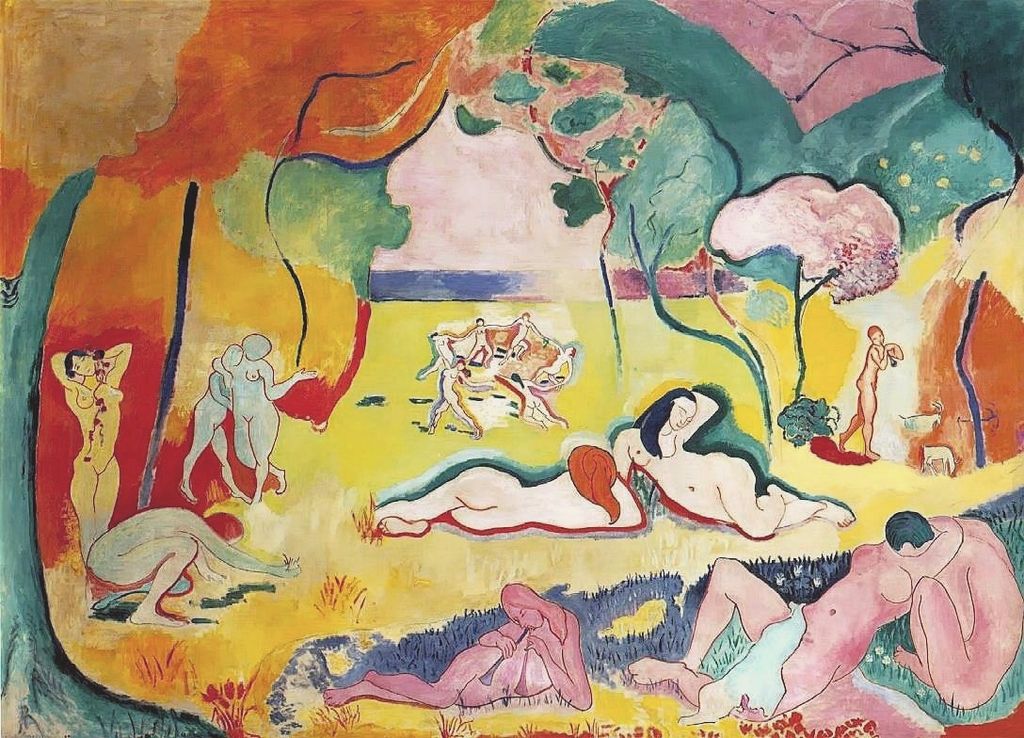

This Salon had no jury, but it did have a committee to arrange the pieces. Some of the Post-Impressionists had a great influence on it. The show was an instant success with thousands of artists submitting their works for exhibition. Some of them were Paul Signac, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gaugin, and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.

Henri Matisse, The Joy of Life, 1905-1906, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

The Autumn Salon (1903-)

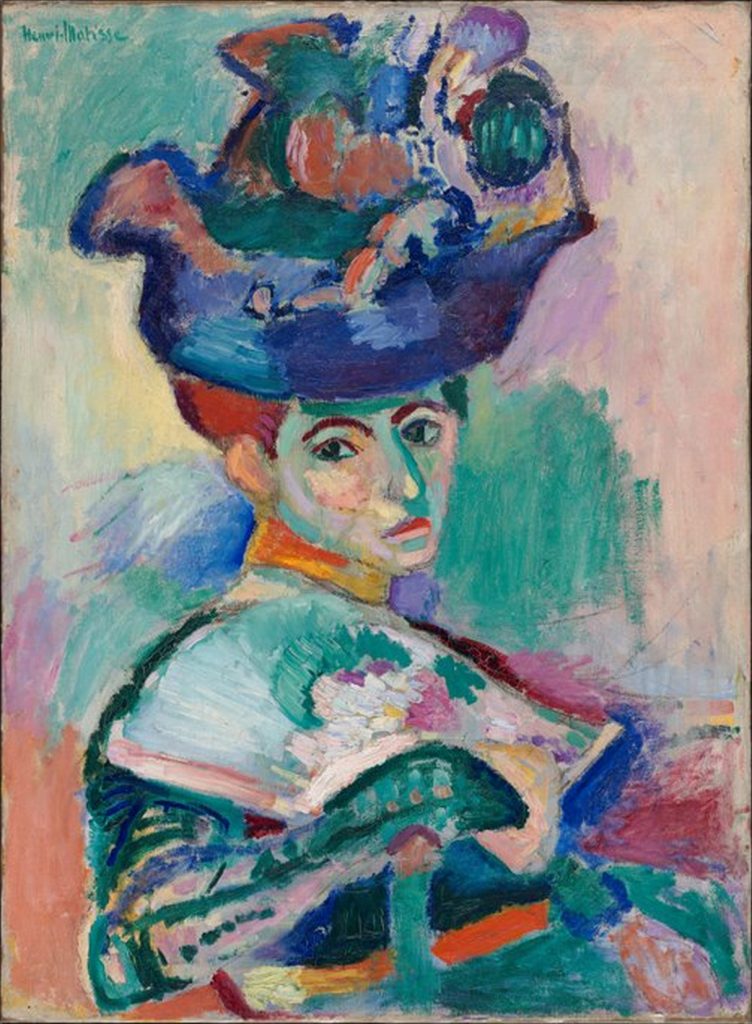

In this one, groups like the Fauvists exposed their works. Just like the Salon of Independents, this one is still running. Indeed, their survival is a testament to their success, in comparison with the disappearance of the Paris Salon.

Henri Matisse, Woman with a hat, 1905, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Honestly, it is clear that none of these examples would have even been considered at the Salon. In this sense, these other options gave not only the artists a chance but also people interested in a change of scenery. Even the state began looking for acquisitions there.

A Schisma: The Nationale

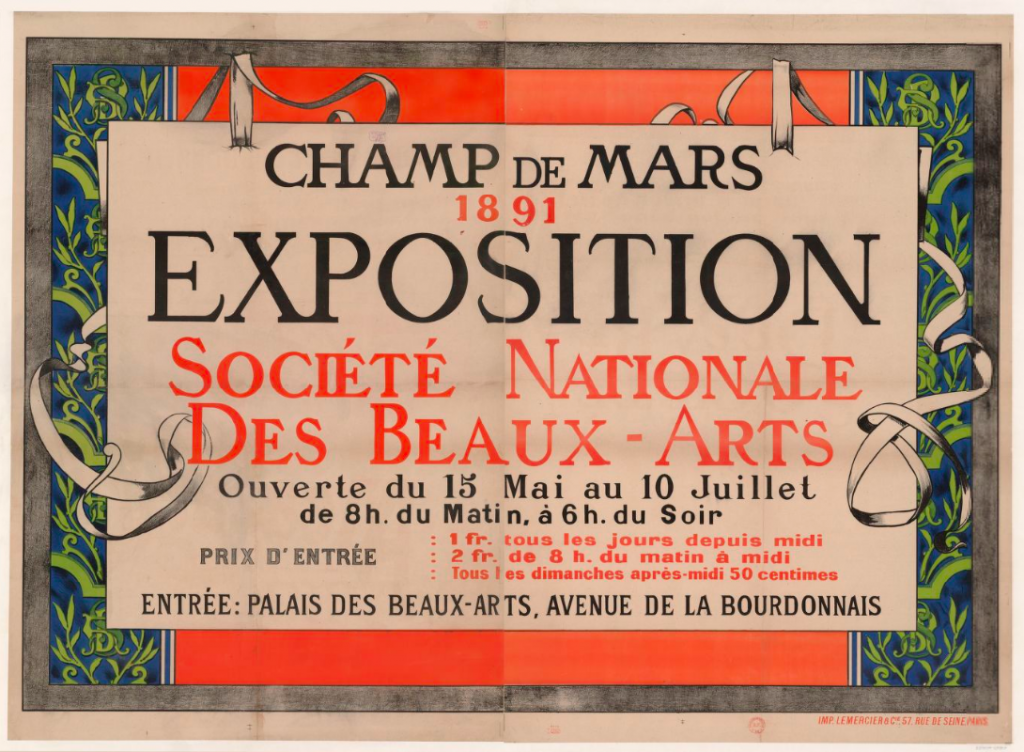

While all that happened elsewhere, inside the Salon things were not looking good. Among the Society of French Artists, there were strong differences too. In essence, there was a group of much more elitist members who wanted stricter judgment to reduce the number of works. As a result, they split and created the National Society of Fine Arts. This organization had its own salon with state support. Therefore, from 1890 onwards, there were two “official” salons. Nevertheless, in the end, they ultimately closed. While the salon was united, it could hold its prominence. But once it fractured, it was only a matter of time.

Poster of the Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts, 1891. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The End of the Paris Salon

At the beginning of the 20th century, the tables had turned for the artists. While academic artists decreased in popularity, avant-guard ones walked in the opposite direction. Artists, critics, art dealers, collectors, the state, and the public started to ignore the Salon until it became irrelevant.

Unfortunately, today the Paris Salon is seen as an obstacle to modern art. Truly, it is not a false statement, but it undermines the importance of this institution. By the second half of the 19th century, the Salon was the only place where artists could make a career and sell their works. Truly, it was the center of artistic life in Europe. Not only that, it provided a place where different classes reunited. From it, a variety of institutions and professions derived. That whole system shaped our contemporary art world.