Christmas in Pop Art: Celebrating Icons and Festivity

Christmas overflows with iconic imagery—Santa Claus, Rudolph, snowmen, candy canes, presents, and sparkling ornaments. These vibrant visuals...

Errika Gerakiti 19 December 2024

Pauline Boty was one of the pioneers of the 1960s’ Pop Art movement in Britain, of which she was the only acknowledged female member. Her versatile portfolio includes paintings, collages, and stained glass pieces. Boty’s work radiates with her confident femininity and explores themes of female sexuality with boldness and flair. Despite her significant contributions, Boty remains relatively obscure in the annals of art history.

Pauline Boty was born in Croydon, South London, on 6 March 1938. She began her artistic journey after earning a scholarship to Wimbledon School of Art in 1954. There, her remarkable beauty earned her the moniker ‘The Wimbledon Bardot’ due to her striking resemblance to the French movie star. Later, in 1958, she continued her education at the Royal College of Art from which she emerged as a prominent figure in the British Pop Art scene.

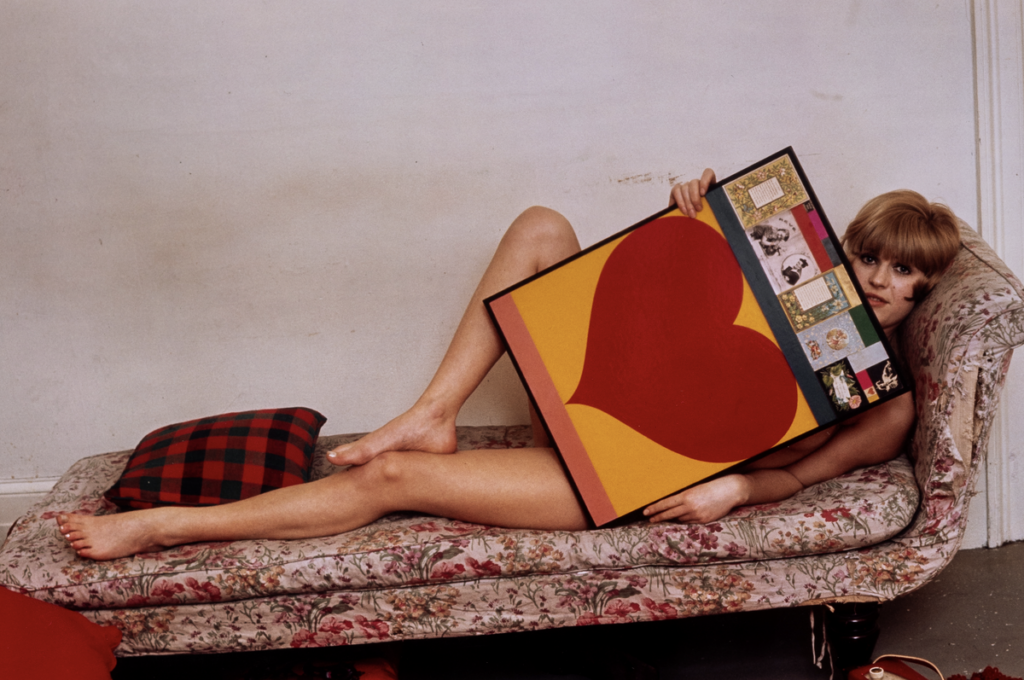

Pauline Boty, 1962. Photograph by Lewis Morley, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK.

Pauline Boty was known for her versatility, spontaneity, and outspokenness. She showcased her talents on the Sixties music program Ready Steady Go!; she wrote poetry; and she appeared in Michael Caine’s film Alfie. Boty seamlessly blended all these traits with her original and politically astute creations.

As the sole acknowledged female member of the British Pop Art movement, her legacy deserves recognition on par with her male counterparts, including Peter Blake and David Hockney. Tragically, Boty’s death at the early age of 28 contributed to her underappreciated status within the art world.

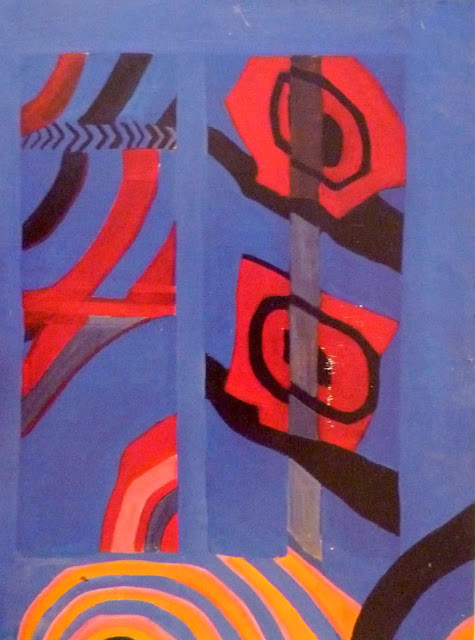

Boty’s initial ventures into “collage painting” showcased a series of geometric panels and abstract forms bathed in vibrant hues of blue, orange, and yellow. During her time at the Royal College of Art she studied in the stained glass department. Gershwin exemplifies the influence it had on Boty’s work, evident in her division of the canvas space into various sections and geometric shapes to compose the overall image. These early compositions laid the groundwork and defined the geometric style that she further refined through her exploration of “collaged” figuration.

Pauline Boty, Gershwin, 1961, private collection.

In the vibrant era of youth-oriented media, primary colors began to saturate the scene, especially in magazines, clothing ads, and album covers. These hues reflected the palette embraced by Pauline Boty. Her contemporaries, like Peter Blake, likewise employed similar color schemes and collage techniques, reflecting the artistic trends of the time. The title Gershwin likely references George Gershwin, the renowned American pianist and composer. This showcased Boty’s tendency to draw inspiration from various media sources surrounding her.

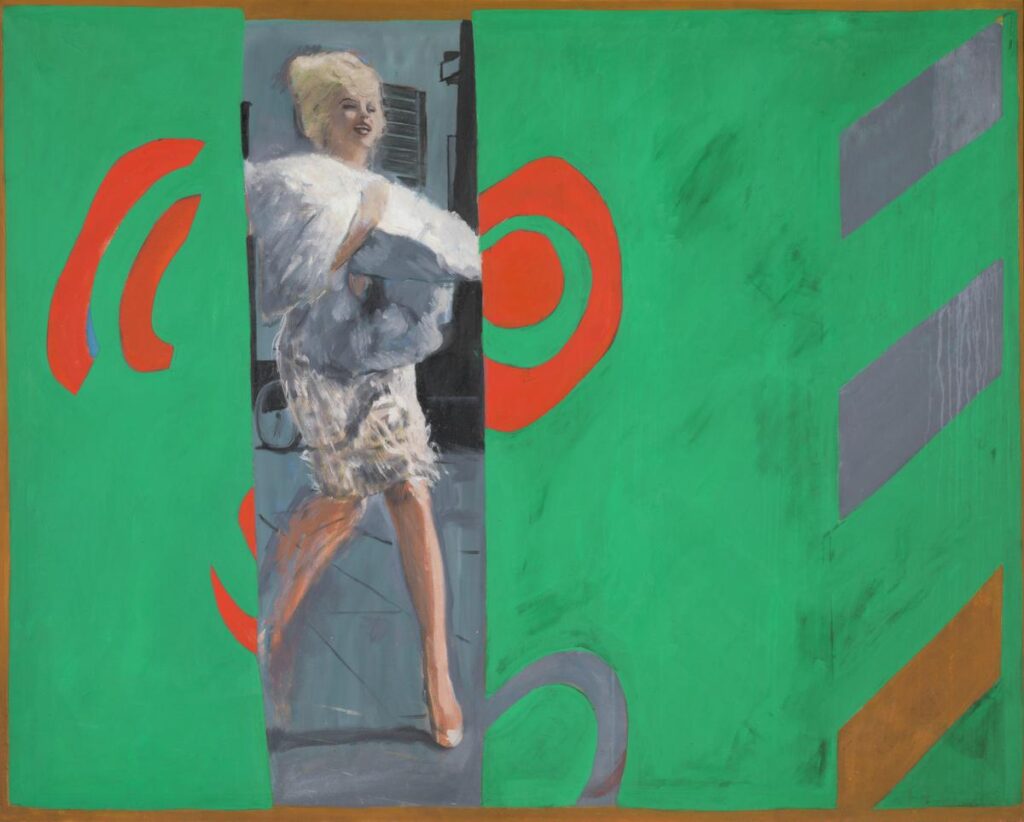

Besides continuing with the vibrant color scheme and abstract shapes, this later work of Pauline Boty features a painted image of Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe. The figure of the actress occupies a narrow piece of canvas indicating the stained glass and collage techniques that influenced Boty’s style. Appearing to press in on her from either side, abstract shapes in shades of green, red, and purple surround Monroe’s portrayal.

Pauline Boty, The Only Blonde in the World, 1963, Tate, London, UK.

Like numerous other images Boty draws inspiration from, this one likely came straight from a press release, possibly at The Seven Year Itch‘s 1955 film premiere. Boty’s fascination with Marilyn Monroe persisted throughout her career. In Boty’s eyes, Monroe embodied both a period of more liberal female sexuality as well as its restrictions. Throughout her career, Pauline Boty also had to deal with objectification from critics, media, and acquaintances while attempting to express her femininity and sexuality. Therefore, Boty could relate to Monroe acknowledging both her power and the challenges she faced as a result of her beauty.

The Only Blonde in the World implies that Monroe is an example by which all other blonde women are referred to. Boty’s satirical choice of title not only ridicules this notion but also sheds light on the pervasive misogyny of the early 1960s society. In this context, beautiful women were often reduced to mere objects of fantasy.

In her later works, Pauline Boty delved into political themes, offering critiques of the male-dominated society she inhabited. Through her art, infused with a distinctly feminine perspective, and her unorthodox lifestyle, she later emerged as a symbol of the feminist movement in the 1970s.

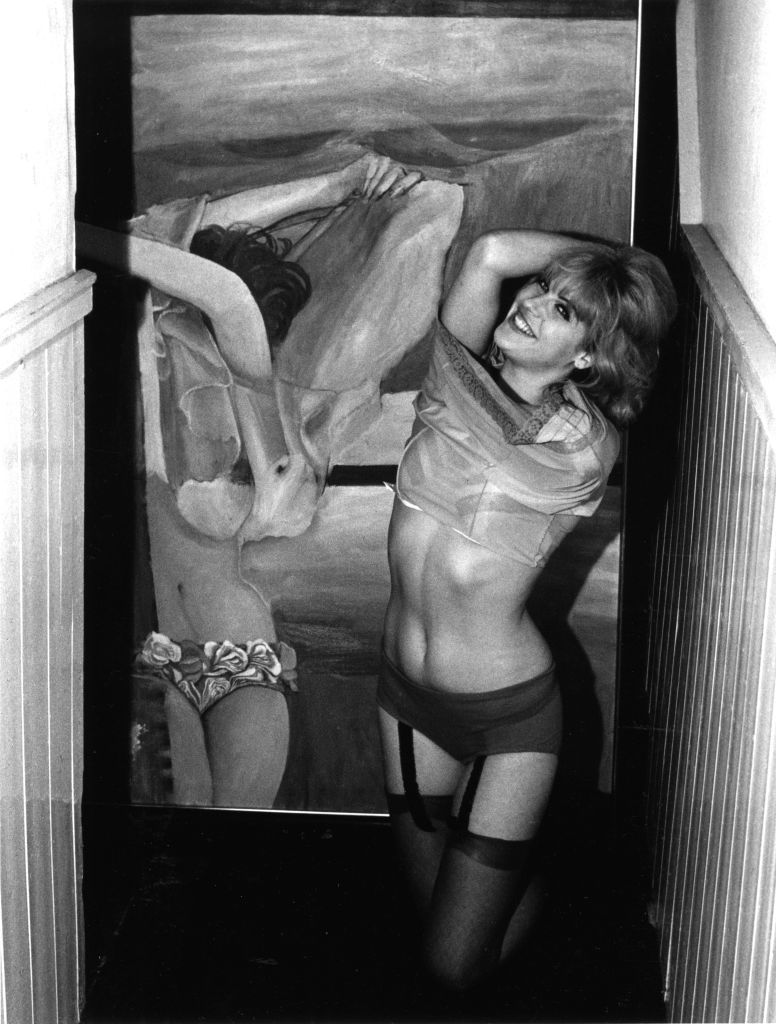

Pauline Boty, 1963. Photograph by Michael Ward, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK.

It didn’t occur to a lot of women at the time to live the way she did – as someone who was not only free in her interests and desires, but who also wasn’t afraid of contradicting herself. She didn’t see why the opposing sides of her personality couldn’t co-exist.

Pauline Boty: British Pop Art’s Sole Sister

As can be seen, Pauline Boty challenged the distinction between men and women’s perspectives on the human body. This theme was particularly explored in her collage series It’s a Man’s World I and II.

The “male” section portrays men engaged in active pursuits within industrial and affluent settings, in stark contrast to the passive depiction of women amidst natural surroundings. For example, Elvis Presley is depicted completely dressed and shown in a close-up of his face. This implies that he is also admired for his musical talent and not solely for his physical appearance. Boty acknowledges a nuanced dimension to this issue, noting that while these men may possess admirable qualities, they function within a societal framework that perpetuates a “man’s world,” further reinforcing gender divides and limitations.

On the contrary, the second painting in this series portrays women as flat representations, devoid of complexity. Boty questions whether these women are depicted as sexually empowered, attractive, and self-assured in their nakedness, or rather as objectified and anonymized with their faces or feet cropped out. Instead of being portrayed as real individuals with multifaceted identities and sexual autonomy, their sexuality is appropriated for the gratification of a male audience, while their other qualities remain unrecognized.

Pauline Boty’s narrative is often recounted with a specific emphasis on the tragic circumstances of her passing. In 1965, Boty received the devastating diagnosis of cancer during a routine medical examination while pregnant. Opting against treatment that would necessitate an abortion, she chose to carry her child to term. Just four months after giving birth to her daughter, she tragically succumbed to the illness at the age of 28. Following her passing, her artistic oeuvre remained largely unseen from the public eye. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that some of her work resurfaced at her brother’s estate in Kent.

Pauline Boty, Color Her Gone, 1962, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, Wolverhampton, UK. ArtUK.

Pauline Boty delivered social critique and irony with her remarkable artistic oeuvre. She engaged in a varied artistic practice, spanning from creating stained glass pieces to crafting playful paintings and collages featuring cultural icons like Elvis and Marilyn Monroe. Nonetheless, she delved into important subjects such as the American race riots and the Cuban missile crisis. Boty defied conventions and empowered her female subjects with sexual agency, challenging traditional gender roles through her bold and provocative works and lifestyle.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!