Georges Braque – The Second Father of Cubism

Everyone knows Pablo Picasso and considers him the father of Cubism. Everyone also knows that success has many fathers. Today, let’s talk about...

Joanna Kaszubowska 1 January 2024

Pablo Picasso, a prolific producer of paintings, prints, ceramics, and sculpture, his work has perhaps become over-familiar. Equally, in recent years his reputation has sunk from a most famous artist of the 20th century to that of a misogynist and an abuser. Whatever you think about Picasso the man, his importance for the development of modern art through a series of groundbreaking and radically different stages is indisputable. Here are the key eight periods of his career.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Artist’s Mother, 1896, Museu Picasso, Barcelona, Spain. Courtesy of Successió Picasso.

Picasso was born into an artistic family and showed precocious talent at an early age. He studied at the Academies in Barcelona and Madrid and frequented Els Quatre Gats (The Four Cats) bar, the center of avant-garde art in Barcelona. His first works employed a realist style with soft brushwork and warm colors, influenced by Spanish artists like Velázquez. This pastel portrait of his mother, drawn when he was only fifteen, is almost impressionistically rendered. However, by the late 1890s, he was channeling the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch. Flattened color blocks, less finished brushwork, and more expressionist tones crept into his work.

Pablo Picasso, The Old Guitarist, 1904, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. © Estate of Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso, Self Portrait, 1901, Musée Picasso, Paris, France. © Succession Pablo Picasso.

Picasso moved to Paris in 1900, living a life of Bohemian poverty and from 1901, he spent a number of years working with a predominantly blue palette. His subject matter remained a blend of traditional and realist themes such as musicians and mothers and children. Flattened, outlined shapes continued to show the influence of Munch, elongated figures showed a debt to El Greco, but the mood is the most important characteristic. The Old Guitarist was painted after the 1901 suicide of his friend and fellow artist, Carles Casagemas which had a profound impact on Picasso. The guitar, picked out in brown, was to become a recurring image and the contorted figure hints at future Cubist experiments.

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltimbanques, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. © Estate of Pablo Picasso

In 1906, Picasso’s mood shifted and a warmer blush appears in his canvases. Saltimbanques were traveling performers and the subject harks back to traditional Harlequin and Pierrot figures. However, there is an almost surrealist oddness about the random and disconnected grouping against a featureless landscape. Many of the circus performers were Spanish, and Picasso clearly identified with them, painting himself as the figure on the left. The unusually large scale, over two meters square and similar in size to Demoiselles d’Avignon, suggests Picasso’s growing confidence.

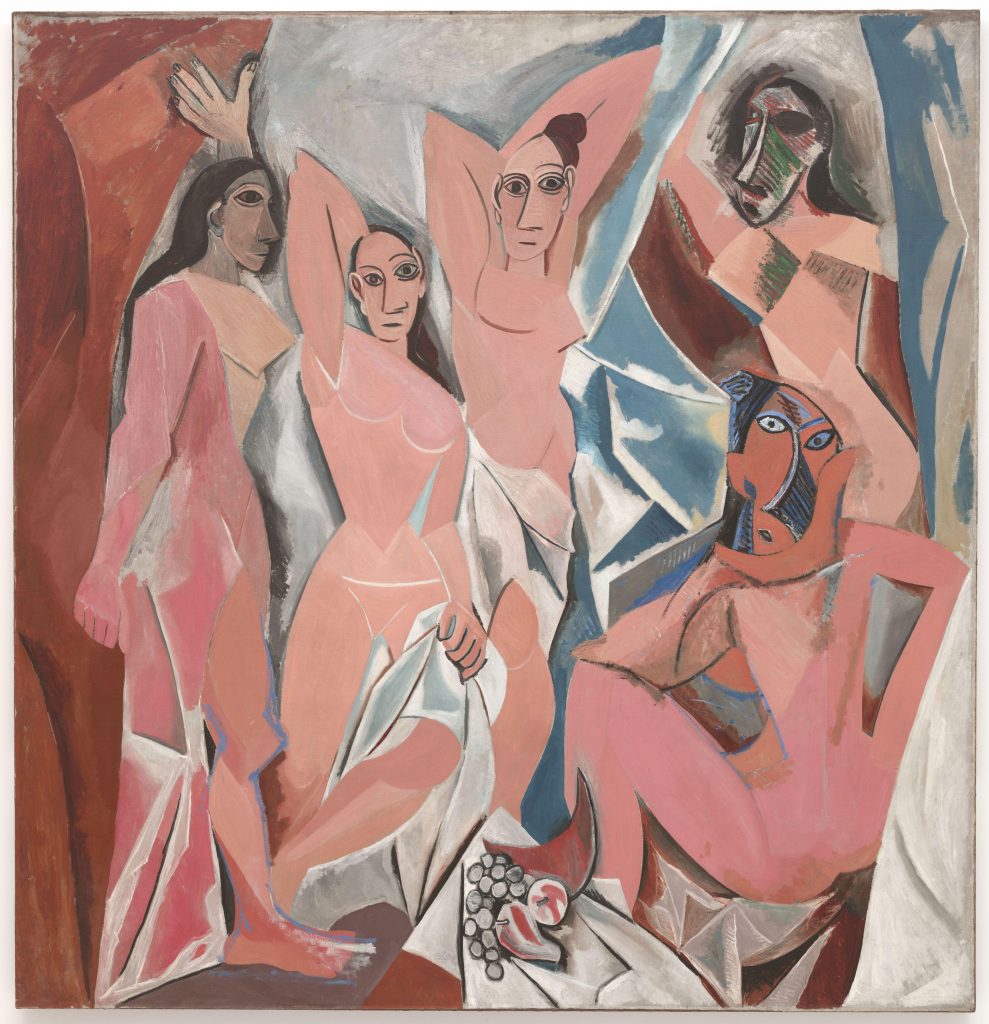

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon), 1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA. © Estate of Pablo Picasso.

In 1907 Picasso visited the ethnographic museum in Paris’ displays of African art. The impact was immediate. The two figures on the right of Demoiselles d’Avignon are painted with African-style masks. Picasso was not alone in his exploration of so-called Primitive art. Paul Gauguin exploited Tahitian culture from the 1890s, meanwhile; Henri Matisse traveled to North Africa in 1906. However, Picasso arguably went further than anyone else. In Demoiselles d’Avignon the hybridized figure on the left has a darker-skinned head, the central women stare out with heavily stylized features and Picasso has abandoned Western concepts of perspective, modeling, and shade.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1910. Pushkin State Museum, Moscow, Russia. © Estate of Pablo Picasso.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon creates a fragmented, disjointed sense of space which was to become the basis for Picasso’s experiments with Cubism. Working alongside Georges Braque from 1908, he used traditional subject matter – mainly portraits like this of art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, and still life – to explore a new language of representation. Analytical Cubism registered all viewing angles simultaneously, fracturing space and time into a complex jigsaw of angles, facets, and planes. These paintings were largely monochrome – color was an added complication. Other artists would take Cubism and run with it—towards light, movement, and abstraction.

Pablo Picasso, Guitar (sheet metal and wire) 1914, Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA. © Estate of Pablo Picasso.

From 1912, Picasso experimented with collage and relief sculpture, using everyday materials to create 3D versions of the objects which he had previously painted. This fed back into his painting in two ways. On one hand, he started to employ lettering and illusionistic tricks, which further emphasized the artificiality of the painted surface. On the other hand, placed a new emphasis on simplification, working with clear, flat, and increasingly abstracted geometry. Sculptures, like Guitar, were even more influential, paving the way for assemblage and construction as well as the use of found objects in 20th-century art.

Pablo Picasso, Mother and Child, 1921, Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA. © Estate of Pablo Picasso.

From 1917, Picasso’s art shifted dramatically. In part, this was inspired by his first visit to Italy, but the change can also be seen in the context of the First World War. Many artists who had enthusiastically embraced modernism and modernity were profoundly shocked by the scale and horror of the War and reacted with a more conservative style. The simplicity and solidity of the figures in Mother and Child owe as much to non-European art as it does to classicism. The subject was one Picasso had tackled many times, but it now had added resonance: he became a father in 1921.

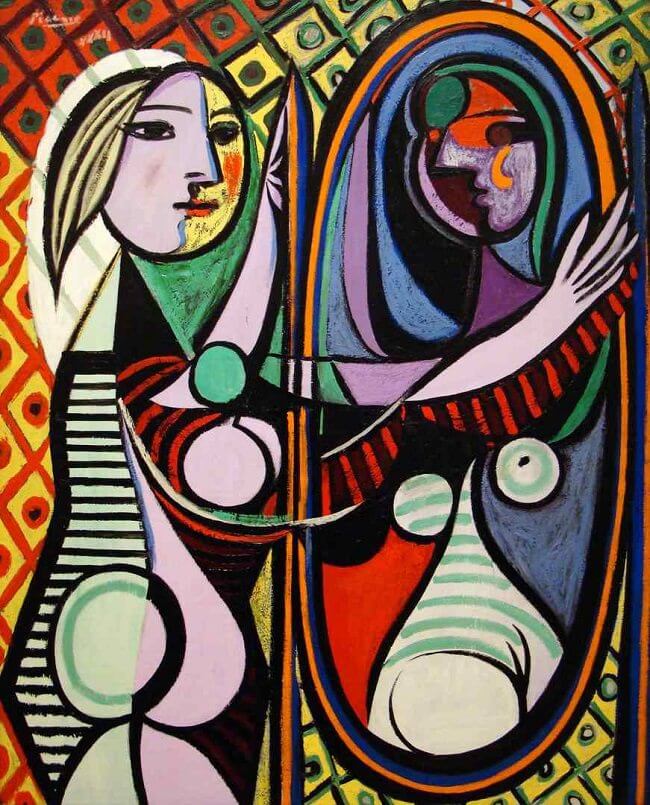

Pablo Picasso, Girl Before A Mirror, 1932, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA. © Estate of Pablo Picasso.

From the mid-1920s, Picasso embraced the new Surrealist ideas which were being explored in Paris by André Breton and others. Synthesizing ideas from his previous work, he created flattened, clearly outlined semi-abstracted forms, disjointed space and features, and recurring motifs like dancers, musicians, and the female figure. For the first time since his early career, the color featured heavily. He also became overtly political, most famously with Guernica (1937).

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain.

Arguably, the innovative period of Picasso’s career was over by the start of the Second World War. The rest of his life was spent revisiting themes and ideas and living out the role of celebrity artist-genius. Through Cubism, he revolutionized two-dimensional representation. Through his experiments with collage, he paved the way for ready-mades and construction. Doing so, he created some of the most iconic images in 20th-century art.

This article was written as a part of the Picasso Celebration 1973-2023 program supported by renowned cultural institutions in Europe and the United States.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!