The Art of Science—Versailles at the Science Museum, London

Have you ever wondered how it would feel to witness the grandeur and opulence of the 18th-century French court? Then you might want to go to London.

Edoardo Cesarino 19 December 2024

The current Philip Guston retrospective at the Tate Modern presents a vast selection of the artist’s life works spanning over 50 years, from the age of 17 up until his death. A conflicted, restless artist, with an ever-changing approach to style, the exhibition poignantly traces Guston’s relentless artistic conflictions in his portrayal of the tumultuous world around him.

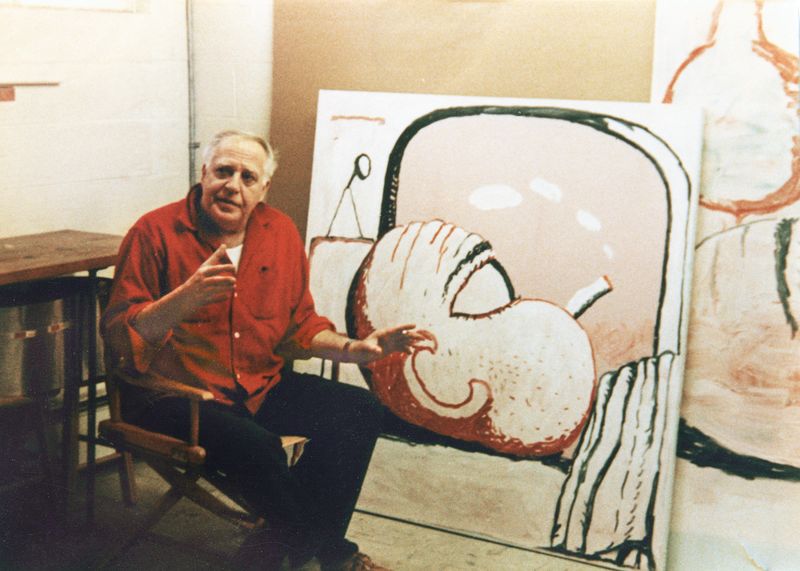

Philip Guston. Photo by Barbara Sproul.

You have to come from somewhere, you don’t come out of the sky.

Holding relevance today, Philip Guston was the youngest child of Jewish immigrants who had fled antisemitic persecution in Ukraine. Born in Montreal in 1913 and moving to Los Angeles in 1922, his childhood was distressing, with his father committing suicide and his brother dying shortly thereafter following a car accident. Art quickly became a way for Guston to deal with the impact of these traumas.

Initially interested in cartoons and drawings, Guston came to respond to a wide range of artistic styles and movements as a child, particularly Surrealism. He had the opportunity to study contemporary art from Europe through visits to Louise and Walter Arensberg’s private collection in Los Angeles. Being exposed to works by Pablo Picasso and Giorgio de Chirico had a profound effect on Guston, as their influences can be seen in the dreamlike images of his early works.

Philip Guston, Mother and Child, c. 1930. Tate Modern, UK. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

The exhibition starts with a concentrated selection of accomplished works Guston completed in his late teens, such as Mother and Child, c. 1930, which featured in his first exhibition at a bookshop in Hollywood in 1933. Completing Mother and Child at only 17 years old, it is clear to the visitor how artistically talented Guston was as a young boy.

Guston drew from multiple artistic influences in the realization of this painting, with allusions to the Mary and Jesus of Renaissance painters, Pablo Picasso’s mother figure, and Giorgio de Chirico’s ghostly cityscapes. He admitted later in life that his exposure to the works of de Chirico as a child encouraged him to pursue his career as a painter, noting his admiration for Picasso and de Chirico in the 1970s. He shared this strong interest in Surrealism with his teenage friends Jackson Pollock and Reuben Kadish.

Upon entering the next room, the focus turns from a conversation on style and artistic influence to a more political, contextual consideration towards pictorial content. Guston grew up politically and was actively involved in militant movements. As a teenager growing up in 1930s LA, Guston engaged with politics and public social art as a means of proactively challenging the growing immigrant, antisemitic and racist beliefs in the US, especially those of the viciously racist hate group, Ku Klux Klan.

Along with his friends, Guston became involved in a group of painters formed under Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Inspired by the Italian fresco paintings of the 1500s, channeling their monumentality and iconography, Guston would create large-scale, narrative-driven murals and paintings, which focused on supporting workers’ rights and their racial injustice protests in the US. He commented of his artistic production in the thirties that “there was a sense of being part of a change, or possible change.”

Rueben Kadish and Philip Guston, The Struggle Against Terrorism, 1934–35, Museo Regional Michoacano, Morelia, Mexico.

One such achievement mentioned is The Struggle Against Terrorism, 1934–35, which was Guston’s first major commission, creating a fresco in Morelia, Mexico, in collaboration with Rueben Kadish. Already we can see Guston’s incorporation of his infamous hooded figures, here being used to draw visual links between the hooded priests of the Spanish Inquisition and the Ku Klux Klan. While his mural painting ceased upon his move to New York in 1936, his commitment to promoting political and racial justice remained with him throughout his life.

Philip Guston, Bombardment, 1937, Tate Modern, UK. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

Seen in Bombardment, 1937, Guston’s painting continues to be politically focused. During the Spanish Civil War, Nazi and Italian Fascist forces bombed the Basque town of Guernica. Many artists responded to this event, and the vortex composition reflects the kind of experimentation artists were carrying out to give dynamism to painting.

Through his teachings at universities in Iowa City and Saint Louis in the 1940s, Guston turned away from public art and muralism and focused on easel oil painting and portraiture. Martial Memory, 1941 (below), is a great example of his new style, as he comes to experiment with space, overlapping forms and dense pictures. He considered this to be his first mature work on canvas and it was also the first to be purchased by a museum. While at the start of the 1940s, his works still reflect similarities with the cityscapes of de Chirico, and the almost fragmentary nature of his works are comparable to Picasso’s Cubist works, the late 1940s bring about another strong change in Guston’s practice.

Philip Guston, Martial Memory, 1941, Tate Modern, UK. © Estate of Philip Guston.

I began to feel that I could really learn, investigate, by losing a lot of what I knew.

Travelling to Europe in 1948 for fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, Guston underwent a creative crisis, and grew increasingly unsatisfied with figurative painting. This was a pivotal time for the artist, bringing about another dramatic shift in his practice. As the figures broke apart, so did Guston, who stated of the period how “everything seemed unsuccessful […] I couldn’t continue figuration.” The artist destroyed most of what he made in Rome, and it was only after travelling around Europe and returning to New York that he felt inspired to paint again.

Affected by the trauma of World War II and the Holocaust, Guston turned to increasingly abstract compositions towards the late 1940s, becoming a part of the abstract scene with good friends Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. He worked intuitively for long periods of time without stepping back from the canvas to analyze the composition. His focus during this time, like many other abstract expressionists, was in the process of creation, as opposed to the finished product.

Philip Guston, The Tormentors, 1947–48. Tate Modern, UK. © The Estate of Philip Guston.

The Tormentors, 1947–48, marks this major transition in Guston’s style. Aware his works of the 1940s were trailing behind the new abstraction promoted by Pollock and others, Guston quickly adopted a new approach. Reluctant to fully abandon the political content of his earlier work, here he depicts abstracted shapes and figures including pointed hoods.

Joining Sidney Janis Gallery in 1955, along with Rothko, de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, Guston had established his reputation as an abstract expressionist painter, known for his expressive use of color and bold brushstrokes. A good example of his work at this time displayed in the exhibition is Dial, 1956 (below). It was the bold, colorful abstract compositions such as this that led to his increasing success as an artist, being selected to represent the US at the Venice Biennale in 1960, and exhibiting his first retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York two years later.

Philip Guston, Dial, 1956. Tate Modern, UK. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, NY, USA; purchase © Estate of Philip Guston.

By the mid-1960s, Guston grows restless, deciding once more to challenge his approach to painting. First in an attempted continuation of abstraction, Guston drains color from his works, which become almost monochromatic versions of his earlier works. And it is here, at this stage, that Guston undergoes perhaps the most intense creative crisis of his life.

In the constant and consuming struggle to rid his works from any kind of figuration, Guston stopped painting completely for a period of 18 months, producing only small, simple drawings of books, furniture and other such banal objects.

Guston finally gave into the impulse to paint figuratively again in the late 1960s, finding the strikingly original style of which he is best known for today.

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969. Tate Modern, UK. Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © The Estate of Philip Guston.

In 1970, Guston revealed his new style at his solo show in Marlborough Gallery, New York. Exhibiting around 30 new paintings, it shocked both critics and close friends, who were dismayed with his departure from abstraction.

Guston’s bold and brave return to figuration saw the hooded figures, which had appeared here and there throughout previous works, become a key symbol of his oeuvre. Born out of his desire to make narrative works addressing the nightmarish injustices he saw in society were these large-scale paintings of hooded figures. While they were symbols for evil, bearing links to the Ku Klux Klan, Guston’s employment of cartoon-like images allow his paintings to challenge projections of strength and intimidation, presenting these figures instead as ridiculous, yet unsettlingly commonplace, raising questions about who is behind the hood, and how violent ideologies are masked in society.

The Studio, 1969, is one example of Guston’s hooded figure, here indicating Guston’s willingness to prompt consideration about his own, as well as the wider art world’s, privilege and accountability for society’s injustices.

Philip Guston, Talking, 1979. Tate Modern, UK. Gift of Edward R. Broida © 2024 The Estate of Philip Guston.

There is nothing to do now, but paint my life; my dreams, surroundings, predicament, desperation, Musa – love, need.

In the late 1970s Guston had health problems. He worked long into the night, painting and smoking. He thought continually about his own mortality. He remained out of the spotlight for the next decade. It was the most productive period of his career, making hundreds of works each year full of his strange and uncanny imagery.

Talking, 1979, was one of his last self-portraits before his death in 1980. Guston’s application of thickly layered black paint was common during the last years of his life, as his compositions linger somewhere between nightmarish and comic.

A few weeks after his 1980 retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Guston died of a heart attack at age 66. The exhibition led to a renewed interest in his work, which has grown ever since.

Probably the only thing one can really learn, the only technique to learn, is the capacity to be able to change.

The exhibition at the Tate Modern expertly succeeds in portraying Guston’s ever-changing approach to painting. Where his practice shifted throughout his career in alignment with his surroundings and lived experience, it is clear that the artist maintained a strong and life-long awareness for his responsibility to bear witness to what he called ‘the brutality of the world.’ Within his experimental styles and artistic approaches, one thing remains constant: Guston forever created works that embodied the complexities of modern life.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!