Georges Braque – The Second Father of Cubism

Everyone knows Pablo Picasso and considers him the father of Cubism. Everyone also knows that success has many fathers. Today, let’s talk about...

Joanna Kaszubowska 1 January 2024

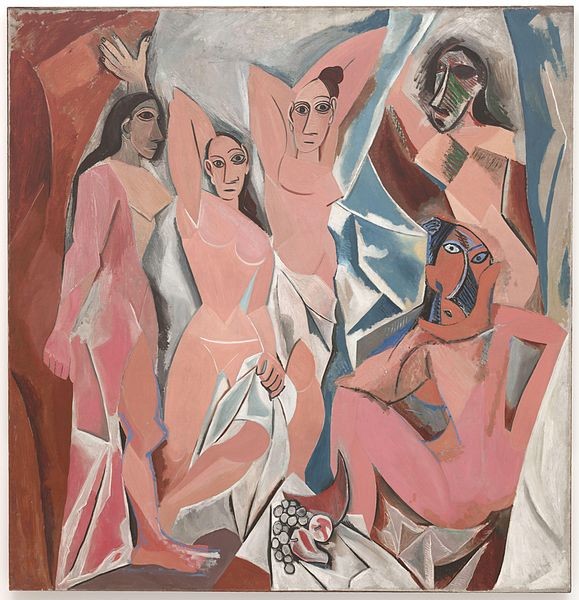

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pablo Picasso created the famous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Georges Braque was immediately inspired and five other avant-garde artists followed. They broke the rules and dived into an entirely new way of seeing and showing objects on canvas. And just like that, Cubism was born.

It’s 1907, and Picasso was feverishly working in Bateau Lavoire, Montmartre. A large canvas of the sex workers from a hometown brothel was driving him mad. What began as a brothel scene morphed into something so radical that it changed art in one stroke. The figures, contorted, draped in very little, aggressively stare out at us. Two appear to be wearing tribal African masks, the latest craze. Bodies are angular, with no soft curves similar to Matisse’s Blue Nude. The figures are painted flatly onto the surface, overlapping shapes from the breasts and hips of these terrifying women. Suddenly, art was not about representation but conceptualization.

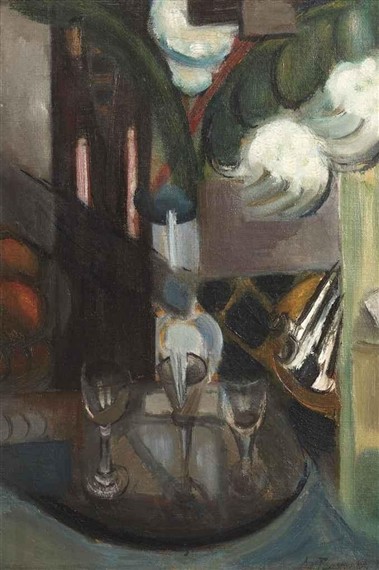

Georges Braque, astounded by this incredible work, began to collaborate. Showing their work in the galleries of Montmartre, the two became known as “Gallery Cubists“, adept at taking still-life compositions and breaking the rules. Forms fragmented into geometric shapes, brush strokes became visible and patterns were formed, helping to flatten perspective and reduce reality.

Their influence was almost instantaneous. Five avant-garde artists: Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Fernand Leger, Henri Le Fauconnier, and Robert Delaunay were inspired by what they saw, but their interpretations went further. Known as “Salon Cubists” because they were showing their work in public exhibitions rather than in private galleries, their palette began with the same monochrome subtlety, but the subjects became more varied through nudes, cityscapes, and domestic interiors such as these examples by Metzinger, Le Fauconnier and Delaunay demonstrate:

Excitingly, Gleizes’ Harvest Threshing (1912) combined the features of “Gallery Cubists” technique with the linear structure to create space and movement.

Fernand Leger began to bring color to the table in his works, using bold shades in non-faceted planes to great effect.

As a consequence of such radicalism, other art forms such as the Italian Futurists and the British Vorticists came into being, changing art in a way that had never been seen before and which sent us into the modern era shaped by Cubism.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!