5 Facts about the Counter-Reformation in Art You Need to Know

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation spreading through Europe during the Renaissance.

Anna Ingram 5 December 2024

21 December 2022 min Read

In the Bruegel Room in Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, 12 paintings hang in the space. They cover the final ten year period of the life of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. One painting, in particular, takes us on a journey across the expanses of winter’s hold on nature: Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow.

The key to this painting is the diagonal movement that crosses the canvas from left to right and back again, bringing the viewer into the pictorial planes through his composition and the way he plays with the diagonals. Within this, we see contrasting scenes depicting isolation and melancholy through populating the scene and producing the sense that we are being pulled into a silent landscape where the deep drifts of snow where you can “feel the cold and sense the audible dullness as the landscape sucks the sound from every little human vignette.”

Bruegel was the first to paint snow in its varying strengths. The crisp, deep snow at the top of the valley is shown by the sunken footsteps and, as we look over the valley with its lakes frozen over, the far mountains look hazy and foreboding as the wind sweeps the light flakes into the air. Even the sky is thick with snow, the steely, deadened color reflected in the frozen surfaces. Despite the frivolity of the skaters, there is a sense of danger of an oncoming storm with the ominous appearance of the crows taking to the air.

The journey for the eye begins with the hunters and their dogs in the foreground:

The figures, faceless and anonymous look weary; feet sinking deep into the heavy snow. Hunched, carrying spears that mirror the diagonals, they look out into the valley below. Their dogs are not racing through the landscape in search of their quarry. Instead, they sniff the ground, tails down and their paw prints are haphazard; demonstrating their confusion after losing the scent. They have not moved forward for a while.

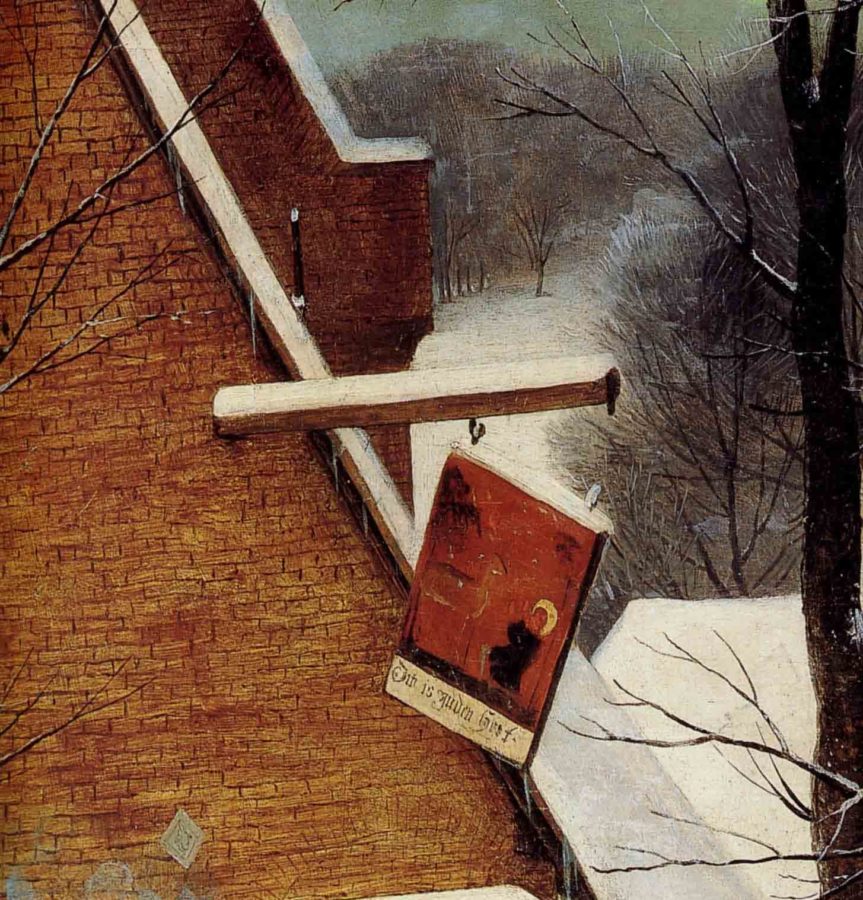

A strong line of trees adds to a sense of division as we notice that close by are villagers outside an inn, roasting corn.

Similarly faceless, and ignoring the men and their dogs, they do not provide a welcome and the hunters are not drawn to the warmth of this blazing fire.

The answer to this division may lie in a small detail:

The inn sign, depicting the patron saint of hunters, St. Hubert and a Stag, hangs precariously over the heads of the villagers. The heavy snow and wind could bring this crashing down.

The hunters are carrying spears that would be used for hunting large game: bears and deer, but they are carrying the carcass of a fox and a bag that is likely to contain birds. This would indicate that their chosen trophy, the stag, has alluded capture. According to George Ferguson in Signs and Symbolism in Christian Art, the stag comes to represent piety and religious aspiration and its symbolism came from Psalm 42:1: “As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O’God.” The religious connection continues with the image of St Hubert, who became the patron saint of hunters because when out hunting, he saw the image of the crucifix between the antlers of a stag and was converted to Christianity.

The Dutch wording, “Dit is Guden Hert” translates to “this is the golden deer,” thereby creating the religious overtone here. The falling sign indicates displeasure at the failure to succeed; the hunters’ paltry killings will not be enough for the winter to come and therefore, they are to continue until they do.

This unfulfilled quest could be the reason why the hunters are no longer welcome in the village. Their gaze is out over the valley at the jollity of the villagers at play.

Bruegel’s strengths lay in revealing peasant life, showing them at work and at play. The winter sports that are shown here; skating, curling, sledging, ice skating, hockey, are familiar to us today, but here, Bruegel shows us that the villagers are unconcerned that the winter draws ever closer and the hardships that will bring will soon be upon them.

And so, we return to our hunters. The path to the village is not one the hunters are about to take. In fact, they are heading out of the picture frame. Are they not to return until they fulfilled their purpose? In an essay in 1954, Professor of Fine Art at Oberlin College said of Bruegel that “Man in Bruegel’s pictures acts under compulsion rather than of his own free will. What he does he must do because he is doing it at a certain time of the year or of his life because he has been trained or taught to do it, or because he is inexorably subject to death, folly, superstition, or other frailties common to men.”

Our hunters have no choice but to fulfill their obligation, despite the unpredictability and ferocity of winter’s grip, and their quest continues.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!