12 Best Shots of the World Press Photo 2024 Exhibition

The World Press Photo Exhibition is a renowned annual event showcasing some of the most impactful visual photojournalism from across the globe.

Nikolina Konjevod 10 February 2025

It all officially began in 1839 in two countries at the same time: in the UK, the Royal Academy announced the discovery of a method of capturing images on paper by the action of light; in France, the government awarded Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre an annuity for his invention of daguerreotype which allowed its release to the public and paved the way for many other pioneers of photography in France.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre is considered the father of modern photography even though the first photograph documented was made by Nicéphore Niépce, a French doctor, who exposed pewter plates in a camera obscura for around eight hours in 1826 (he’d been experimenting with his brother for 10 years already!) Niépce strove to reduce the exposure time and so in 1829, he got in touch with a camera obscura specialist, Daguerre. In 1835 together they produced the first daguerreotype, striking with richness of detail and precision. However, each image could be produced only once and was very fragile, two reasons for which the experiments on improving daguerrotypes continued and within 20 years of their invention, daguerrotypes went out of use.

Gustave Le Gray, born in 1820 is considered one of the most important French pioneers of photography not only because of his technical innovations but also because he taught the art to many notable subsequent photographers. He is respected for the extraordinary imagination and innovation he brought to picture making. As demonstrated by the photo above – to achieve the seascapes Le Gray had to combine two separate negatives, as the photography materials were still too limited to contain both at once. As the method worked, he also utilized it for landscapes. Le Gray’s biography deserves a separate article, as he worked for Napoleon III, went bankrupt, escaped to Sicily, was abandoned by a friend in Malta, and ended up settling in Egypt.

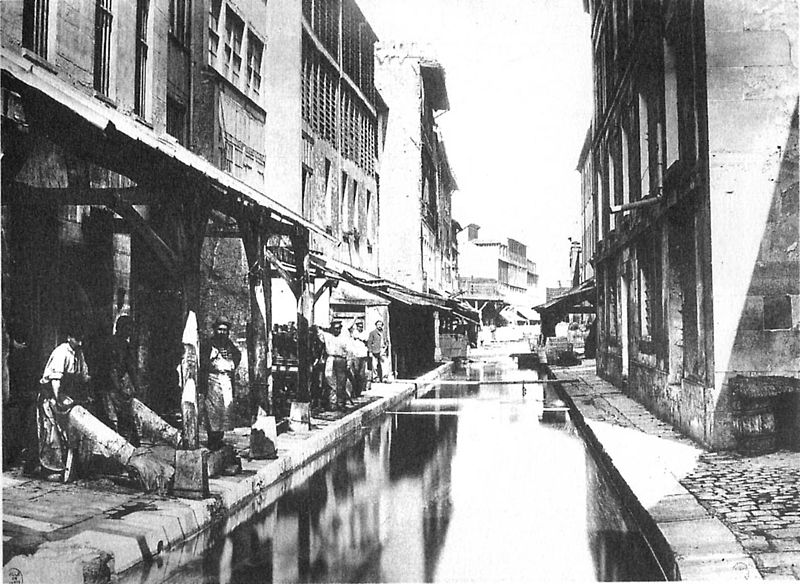

To begin a splendid career in Paris, Charles-François needed a new surname since his original name, Bossu meant hunchback in French… By the 1850s Charles Marville was already recognized and working for the Emperor who commissioned him to document the transformation of Paris under the direction of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. In consequence, thanks to Marville and his preservation of Old Paris in pictures, we can see what the dodgy narrow streets looked like, and what they were turned into after the completion of the great urban project.

This picture sums up the painterly photography of Eugène Cuvelier well, a member of the Barbizon School. Instead of bringing an easel and paints, Cuvelier brought a camera to capture the beauties of the forest along with his friend Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. Taught how to make pictures by his father, Cuvelier believed that in order to become a real photographer, one needed to be an artist capable of capturing the same sentiment as painting. We can tell he succeeded as Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and others from the Barbizon School were influenced by his photographs and sensitivity.

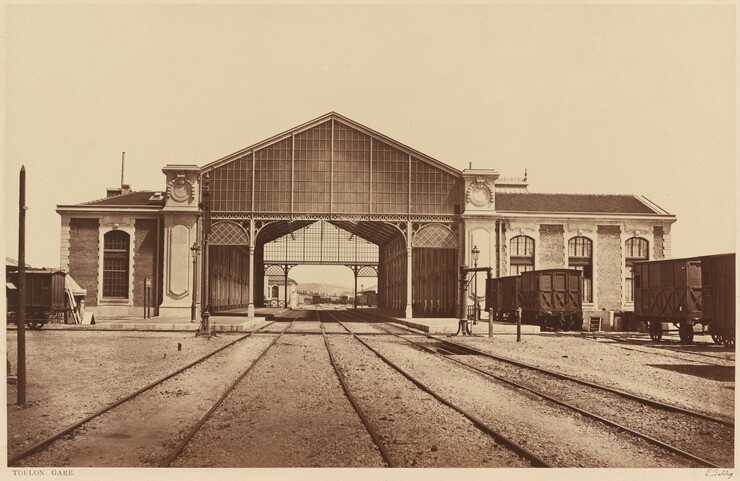

Another photographer-painter was Édouard-Denis Baldus, who in the city register signed himself as “peintre photograph” (painter photographer), as he had been schooled to become a painter and later turned to photography in 1849. His painterly eye and talent made him extremely successful, gaining him an important commission to document architecture in France. His largest commission arrived in 1855 when he was asked to track the construction of the Musée du Louvre with his camera.

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, better known by his art-name Nadar, was the most popular portrait photographer in Paris. A friend of many artists and bohemians in Paris, such as Charles Baudelaire and the Impressionists, he was obsessed with the idea of fame. As his biographer Adam Begley tells, he adored all those who were famous and was fixated on the idea of becoming famous himself, which I suppose helped him understand the celebrities of the 19th-century Paris and make their portraits, which stroke with psychological depth and silent understanding.

To close the survey of the pioneers of photography, I’ve chosen a curious case. Guillaume-Benjamin-Amant Duchenne de Boulogne was above all a neurologist and physiologist who, passionate about photography, saw its potential as an aid for scientific research. In the mid-1850s, he conducted research on human emotions and how they are expressed in people’s faces. In order to study the movement of facial muscles, he applied electrical currents to his subjects’ faces which he subsequently photographed. The induced expressions found their place in a lexicon of human emotions, which led to the publication in 1862 of a treatise on physiognomy – a theory that assumed a relationship between a person’s appearance and their character.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!