10 Iconic Floral Still Lifes You Need to Know

Flowers have long been a central theme in still-life painting. Each flower carries its own symbolism. For example, they can represent innocence,...

Errika Gerakiti 6 February 2025

Between 2019 and 2023, coronavirus hit the globe and changed millions of lives. But the uncertainties caused by COVID have resonated with a much earlier point in human history. We might find a similar sentiment when looking at the ways artists depicted plagues.

Plagues were seen as untreatable for centuries. The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. It resulted in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351. 200 million!

The Great Influenza from January 1918 to December 1920 (also known as the Spanish flu) infected 500 million people around the world. This amounts to 27% of the world population at the time. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million and possibly as high as 100 million. 100 million! And it happened only 100 years ago.

Or take HIV/AIDS. It is estimated that since the beginning of the epidemic in the 1980s, 78 million people have been affected, and about 35 million have died of it. There is no cure or vaccine for it yet, although antiretroviral treatments can maintain a near-normal life expectancy. Still, close to 13,000 people with AIDS in the United States die each year. The peak of this pandemic happened only 30 years ago.

From December 2019 to May 2023, over 776 million COVID cases have been identified, and 7 million deaths have been reported. As of April 2024, 675 million people have recovered. While COVID is no longer considered a global health emergency, there is something we can learn from it in comparison with art history and masterpieces.

During the Black Death (1347–1351), skeletons and the Dance of Death were very common motifs. There is no surprise here. More than 30% of the European population died in the epidemic. Cities such as Venice lost up to 60% of the inhabitants. Half of the Paris population was killed. Giovanni Boccaccio in his Decameron (1353) wrote:

In men and women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumors in the groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg … From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, now minute and numerous. As the gavocciolo had been and still was an infallible token of approaching death, such also were these spots on whomsoever they showed themselves.

Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron, 1353.

Following this, victims would develop an acute fever and start vomiting blood. Most would die two seven days after initial symptoms.

Contemporary reports tell of mass burial pits dug in response to the large numbers of dead. Before 1350, there were about 170,000 settlements in Germany. By 1450, this number dropped by nearly 40,000 due to the Black Death. In this miniature, we see how the citizens of Tournai, Belgium, were burying the dead en masse. There are fifteen mourners and nine coffins, all crammed into the small space. Interestingly, the face of each mourner is given individual attention. Each conveys genuine sorrow and, even more, genuine fear.

Dated to the mid-14th century, the Rylands Haggadah from Catalonia, one of many illuminated Passover Haggadah, celebrates the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt. These two scenes illustrate one of the ten plagues that Yahweh inflicted on the Egyptians for enslaving and oppressing the Israelites. The epidemic of boils didn’t spare even the Pharaoh, presented here as a Medieval king. Notice the details of this illustration, like the dogs licking the boils on their owners’ bodies!

The horror of the Black Death became a hotbed for very dark humor. The Dance of Death (Danse Macabre) is a great example. Such a theme first appeared in narrative poems about encounters between the living and the dead. Most often, the living characters were proud and powerful members of society, such as knights and bishops. The dead interrupted their procession: “As we are, so shall you be” was the underlying message, “and neither your strength nor your piety can provide escape.”

Clusone’s Dance of Death is a part of The Triumph of Death scene. Characters from different social classes join the skeletons in the fatal dance of death. Death itself is represented as a crowned skeleton queen with scrolls in her hands. Two skeletons accompany her, killing people with a bow and an ancient arquebus. There is also a group of powerful but desperate mortals who beg for mercy and offer their valuables. Death is not interested in their mundane wealth however, she only wants their lives. Beneath her feet, the corpses of an emperor and a pope lie in a marble coffin. They are surrounded by poisonous animals, symbols of a fast and merciless end.

We are not in the Middle Ages anymore, but The Triumph of Death by Flemish Renaissance master Pieter Bruegel the Elder, with a very deadly swing, shows what the Black Death could mean for an average European town. OK, maybe I’m exaggerating a little, but an army of skeletons wreaking havoc across a blackened, desolate landscape makes a hugeimpression to this day. Fires are burning in the distance. The sea is full of shipwrecks. Everything is dead, even the trees and the fish in the pond. This painting depicts people of all social backgrounds, from peasants and soldiers to nobles, as well as a king and a cardinal. Death takes them all indiscriminately.

The Black Death was more than a medieval horror, it kept coming back. For more than the next 300 years, the plague became a regular part of everyday life in Europe. Terrible outbreaks periodically devastated cities. Look at this this way, the whole story of Europe between the 14th to the late 17th century was constantly marked by the plague. Some great artists, probably including Hans Holbein and Titian, died from it.

Meanwhile, others tried to fight it with art, like Tintoretto. He painted his greatest works in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice, a building dedicated to a plague-protective saint. Death from the plague was a regular part of human life at the time.

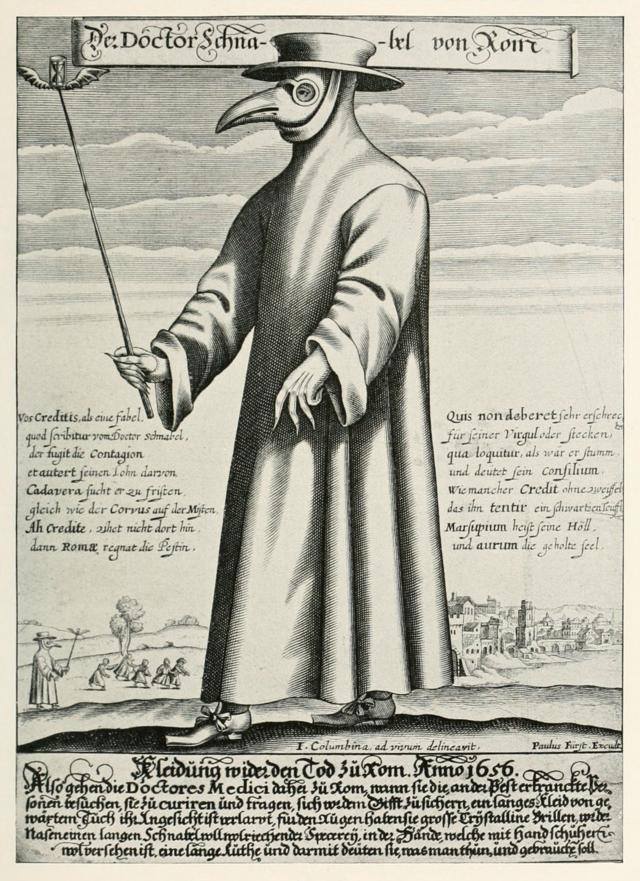

In this etching, we see a plague doctor, the harbinger of imminent death. The costume depicted was used in France and Italy in the 17th century, which usually consisted of an ankle-length overcoat, a bird-like beaked mask, along with gloves, boots, a wide-brimmed hat, and another over-clothing garment. The mask had glass openings in the eyes and a curved beak-shaped face with straps that held the beak in front of the doctor’s nose. The two small nose holes on it were a type of early respirator that held sweet or strong-smelling substances (usually lavender). The beak could hold dried flowers, herbs, spices, camphor, or a vinegar sponge. The design was to keep away bad smells, known as miasma, which were thought to be the primary cause of the disease. Germ theory later disproved this.

Plague exemplified Arnold Böcklin’s obsession with nightmares of war, pestilence, and death. Böcklin was a Symbolist. And here, his personification of Death rides on a winged creature, flying through the street of a medieval town. According to art historians, he took inspiration from news about the plague appearing in Bombay in 1898. Although there is no straightforward, visible evidence of Indian inspiration (Symbolists always used as ambiguous and universal symbols as possible) Böcklin created a scene that the creators of the Game of Thrones would not be ashamed of.

The 20th century brought two World Wars, the Holocaust, unimaginable atrocities, and the Spanish Flu. The horrific scale of this pandemic is hard to fathom. The virus infected 500 million people worldwide and killed an estimated 100 million victims. For perspective, that’s more than all of the soldiers and civilians killed during World War I combined.

It had symptoms of normal flu: fever, nausea, aches, and diarrhea. Many developed severe pneumonia as well. Also, dark spots would appear on the cheeks, and patients would turn blue, suffocating from a lack of oxygen as their lungs filled with a frothy, bloody substance. Unlike a typical flu, where the highest mortality is in infants and the elderly, the 1918 flu also struck down young, healthy adults.

Egon Schiele was one of the great artists who died from it. The Family was unfinished at the time of Schiele’s death and initially was titled Squatting Couple. It was one of his last paintings. In it, we see Schiele himself with his wife Edith and their unborn child. In his last letter, he described his concern for her, writing: “Dear Mother Schiele, Edith got the Spanish Flu eight days ago and has pneumonia. She is six months pregnant. The disease is very serious and life-threatening; I am preparing myself for the worst”. Edith died of Spanish flu in the sixth month of her pregnancy. Three days after she died, Egon did too.

Among other famous artists who died of the Spanish flu were Gustav Klimt, Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, and Niko Pirosmani. Edvard Munch caught it, but he survived. Munch painted this work in 1919. He created a series of studies, sketches, and paintings where, in a very detailed way, he depicted his closeness to death. As we see here, Munch’s hair is thin, his complexion is jaundiced, and he is wrapped in a dressing gown and blanket.

By the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic had come to an end. Those that were infected had either died or had developed immunity.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the outbreak of HIV and AIDS swept across the United States and the rest of the world. The disease originated decades earlier though. Today, over 78 million people have been infected with HIV and about 35 million have died from AIDS since the start of the epidemic. The virus is transmitted through bodily fluids such as blood, semen, vaginal fluids, anal fluids, and breast milk. In the 1980s the public considered AIDS a “gay disease”, it was even called the “gay plague” for many years. Historically HIV spread from person to person through unprotected sex, sharing of needles for drug use, and through birth.

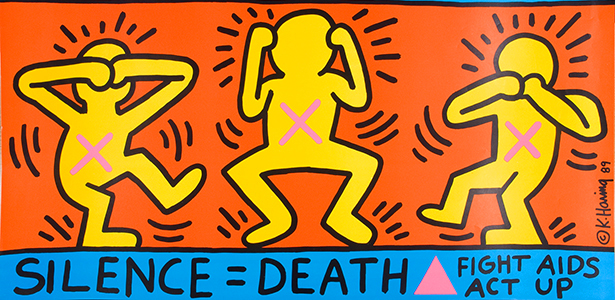

Keith Haring designed and executed this poster in 1989 after he was diagnosed with AIDS the previous year. In 1989 one American was diagnosed with HIV every minute and four people died of AIDS every hour. By 1991 the epidemic had claimed the lives of 100,000 Americans. The poster depicts three figures gesturing “See nothing, hear nothing, say nothing”. This implied the struggles faced by those living with AIDS and the challenges posed by individuals or groups that fail to properly acknowledge and respect the epidemic. The state of information about AIDS/HIV in the United States in the 1980s was truly horrendous. Misinformation was common, the American government’s response to what was happening was shamefully inadequate, and the medicines and medical care were costly. People with HIV were left by themselves.

Keith Haring died of AIDS in 1990 at the age of 31.

David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Falling Buffalos) is one of the artist’s best-known works and perhaps one of the most haunting artistic responses to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. In this photo montage, we see a herd of buffalo falling off a cliff to their deaths. The falling buffalos evoke feelings of doom and hopelessness, making the work extremely powerful and provocative. Made in the wake of the artist’s HIV-positive diagnosis, Wojnarowicz’s image draws a parallel between the AIDS crisis and the mass slaughter of buffalos in America in the nineteenth century. It reminds viewers of the neglect and marginalization that characterized the politics of HIV/AIDS at the time.

Wojnarowicz died of HIV/AIDS in 1992.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!