Historical Context

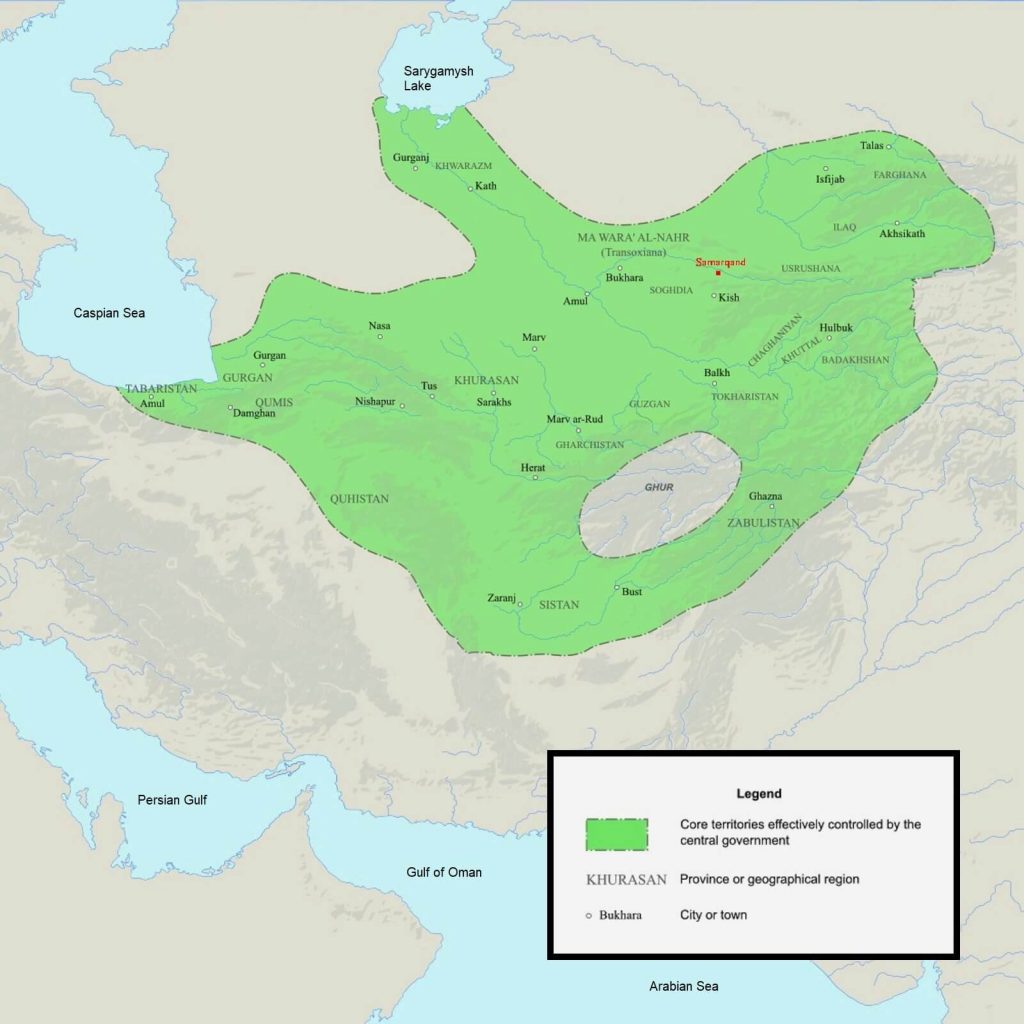

The Samanid Empire was a large Sunni Islamic nation that lasted from 819 to 999. It stretched across regions that now include modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The empire’s capital was the city of Samarkand, in modern Uzbekistan, from 819 to 892. Samarkand, a major Silk Road trading post, was at the center of the Persian Renaissance or Iranian Intermezzo when Iranian Islamic culture and its arts had a strong national revival. It was during this flowering artistic period of international trade that Plate with Arabic Inscription was created.

General Composition

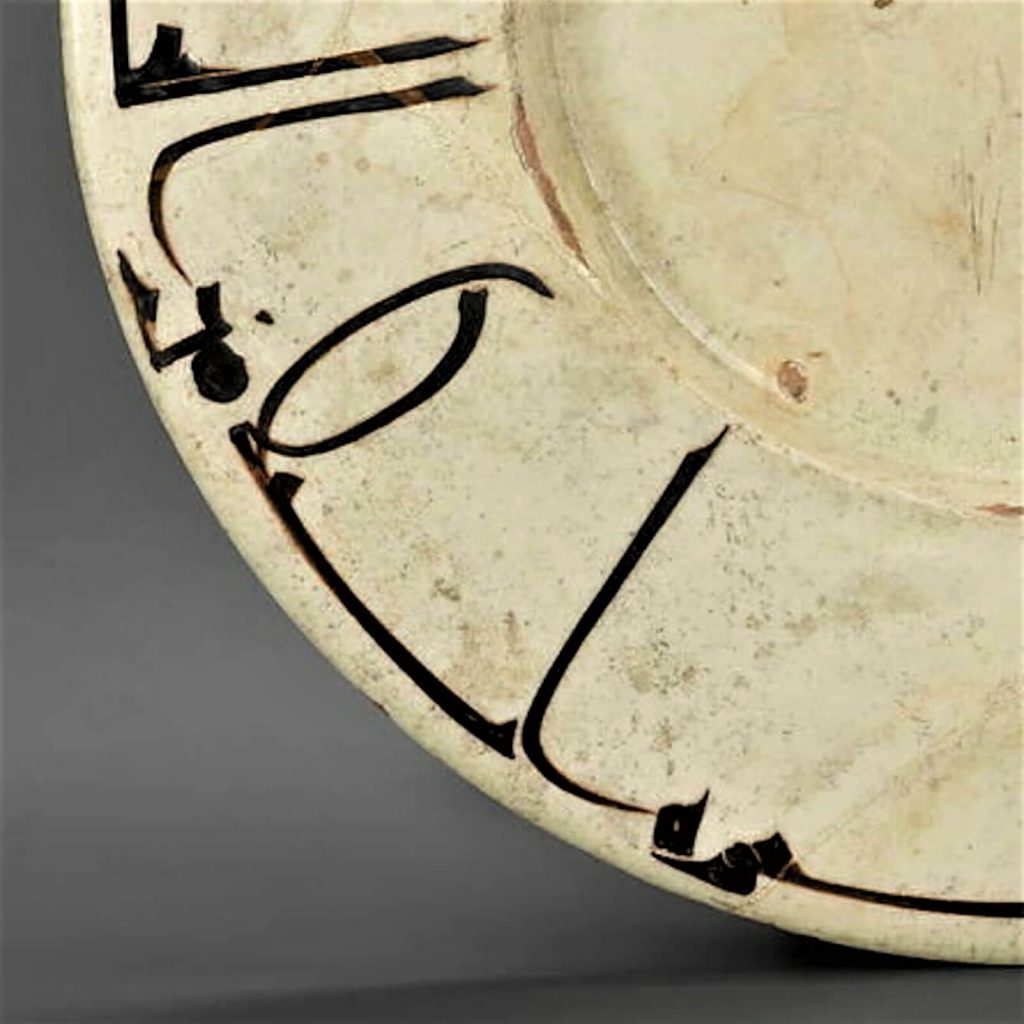

Plate with Arabic Inscription is a large piece of dishware measuring a diameter of 14.8 inches (37.6 centimeters), a height of 4.3 inches (10.8 centimeters), a thickness of 0.3 inches (0.7 centimeters), and a weight of 5.9 pounds (2.7 kilograms). It was made in Samarkand from local clay during the last quarter of the 10th century.

The plate was formed through a straightforward but timely process. First the local dark pink clay was gathered and placed on a pottery wheel. The wheel was then spun, allowing the potter to shape the clay into the desired form. Once air-dried, next the clay plate was dipped into a white slip, or slurry, to evenly coat the surface with a white finish. After this slip dries, a calligrapher uses black slip to paint the calligraphic words along the plate’s wide marli or raised border. The black slip dries and the plate is then coated in a transparent glaze. Finally, the piece is fired in a kiln, developing an attractive glossy sheen that is both durable and waterproof.

Inscription

The black calligraphy encircling the white plate is in the Arabic language. It is written in the Kufic script, an early angular form of the Arabic alphabet, which is used frequently in decorative inscriptions. The plate’s inscription reads the following:

Secular Adage

The inscription is not a religious text. It is an adage providing practical advice for a secular life. This advice would have been intended for an affluent individual such as a successful merchant and not for a royal patron. Its reference to food is also highly appropriate for a piece of tableware. Similar proverbs appear in other contemporary examples that codify and strengthen the social and moral codes valued under the Samanid Empire. Hospitality and generosity were two of their most important values, and appropriately this plate’s inscription mentions magnanimity (condition of being magnanimous or generous).

Calligraphy

Plate with Arabic Inscription is typical of the black-on-white ware or Samarkand ware unearthed in the cities of Nishapur and Samarkand dating from this period. The plate and its contemporaries have a monumental simplicity with their monochromatic schemes. The decoration is reduced to black lines on a white form that embraces minimalism. The calligraphy is elegant and harmonious. Shortening, bending, and elongating the letters transforms the words into nearly abstract patterns. Vertical flourishes punctuate the script’s horizontal flow at rhythmic intervals.

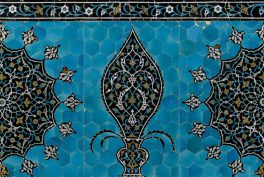

Islamic Minimalism

Minimalism and abstraction are not modern Western innovations. This plate shows that Eastern and Middle Eastern cultures embraced these concepts centuries before they were adopted in the West. However, Islamic minimalism was an infrequent occurrence as most surviving Islamic arts are covered in lavish colors and ornate patterns. Therefore, Plate with Arabic Inscription is more impressive for its artistic rarity and its exploration of unusual themes. It combines minimalism and abstraction. It fuses art and utility. Why can’t all useful objects be so beautiful?