Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

Sister Plautilla was a Florentine nun and artist who lived in the 16th-century Italy. After centuries of neglect, her work is finally being rediscovered, and she is the earliest known female painter from Florence.

In the Italian Renaissance, women could only manage to become artists under very specific circumstances: they could either have access to artistic training through birth into a family of artists, like Lavinia Fontana, or through an exceptional education, as in the case of Sofonisba Anguissola. Plautilla Nelli, however, fits into a third scenario of artistic development: nuns in monasteries.

Pulisena Margherita Nelli (1524-1588) joined the convent of St. Catherine of Siena in 1538. There, at the age of 14, she took the name of Sister Plautilla. In her father’s testament, she was given a common choice among young women at the time: marriage or convent. Sending a daughter to a convent was a cost-saving choice (a cheaper option to marriage). And so, in this Dominican convent in Florence, Pulisena and her sister became nuns.

Being a nun wasn’t as confining as we may think today. Monastic environments could be enriching worlds, as was the case for Nelli. In the convent, in addition to praying, she was encouraged to learn and draw. As a nun, she was able to develop herself as an artist, which may not have been possible if she had become a wife and a mother, engaged in the domestic duties expected from women at the time.

There is currently no certainty on how Sister Plautilla learned to paint. Some say she was self-taught, learning how to paint by copying the works of Fra Bartolomeo and other artists. Others argue she could have studied with other nuns, though there is no concrete evidence of that so far. Either way, she became an outstanding artist.

Nelli not only painted small devotional pieces and miniature illustrations, but also large-scale paintings (extremely unusual for female artists). She was praised by many and the demand for her devotional works was high, especially from the elite of Florence.

She, beginning little by little to draw and to imitate in colours pictures and paintings by excellent masters, has executed some works with such diligence, that she has caused the craftsmen to marvel. (…) And in the houses of gentlemen throughout Florence there are so many [of Nelli’s] pictures, that it would be tedious to attempt to speak of them all.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Vol. 05. Gutenberg Project.

However, the magnitude of her work doesn’t lie only in her large-scale paintings or in her popularity. Aside from this, Nelli also ran an all-female artists’ studio in the convent, where she supervised at least eight other nun artists. Personally training other female artists, she guided a vital artistic community.

By selling their devotional works to the nobility, the nuns managed to become financially self-sufficient. Thanks to that, they could pay for expensive materials and for the work of assistants when needed. By the end of the 16th century, their convent was a well-known art center and they painted not only for private homes but also for other churches.

Leonardo da Vinci’s painting is most likely the best-known representation of the Last Supper. However, the same scene has been portrayed by many other artists throughout art history, and, around 50 years after Da Vinci, a female artist offered her interpretation of it. Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper is the first known representation of this episode painted by a woman.

Created for the refectory of the convent of St. Catherine, the almost seven meter wide canvas is one of the largest works made by an early modern female artist. In a society that didn’t allow women to study anatomy, the fact that she was able to paint 13 life-size male figures is impressive. Her attention to detail is striking; if you look close enough, you can see not only the tendons and veins in their hands but also each fingernail.

After being neglected for almost five centuries, the painting was recently restored and it is now on permanent display in the Museum of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

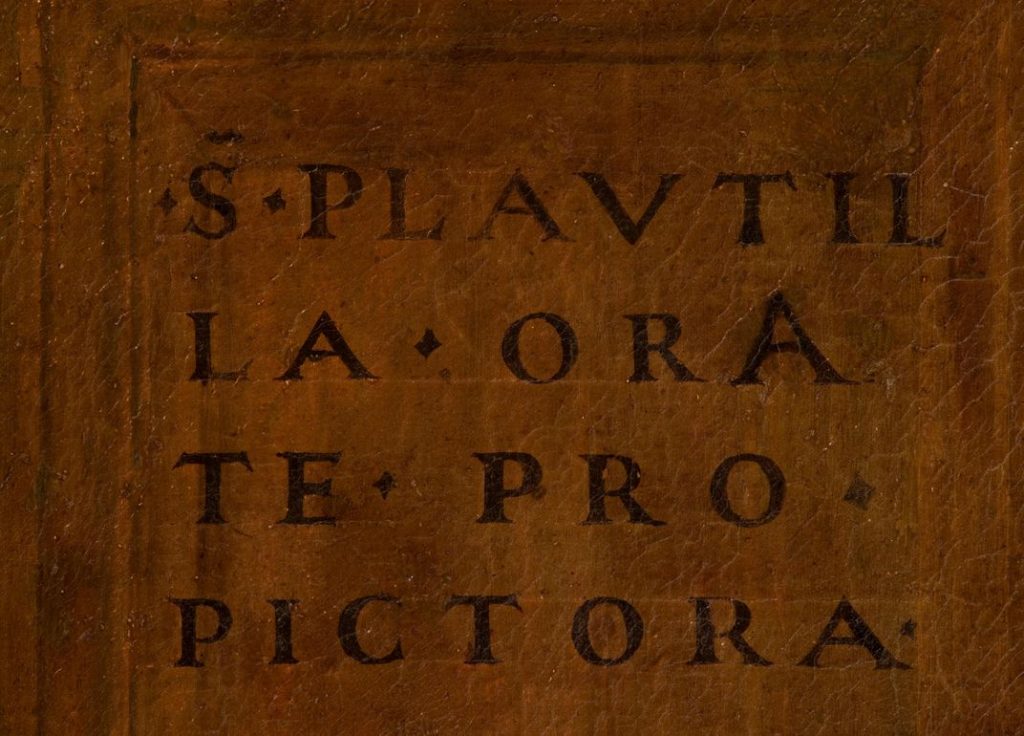

It is important to know that Nelli’s hands weren’t the only ones in charge of this painting. Advancing Women Artists, the organization that supervised the restoration, states that it was painted in “workshop style” – meaning that different artists contributed to it. In this case, it means the painting was a collective work with other nuns in the studio. It is still Nelli’s signature that appears on the bottom of the canvas, though, followed by “orate pro pictora” (pray for the paintress).

Even though she was well-known during the Renaissance, Plautilla Nelli’s work was lost in art history, until it was almost completely forgotten. In 2006, only three works were confirmed as hers, but now we are already aware of almost 20 of her pieces. Through recent efforts in rediscovering early modern female artists, her paintings found their way back into the spotlight.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!