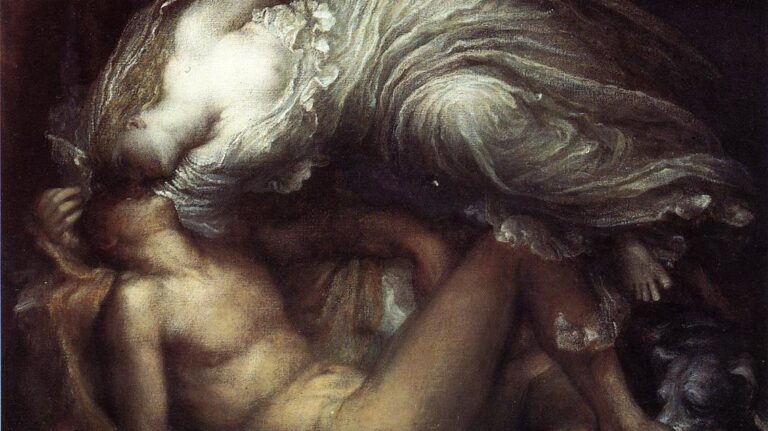

Is there anything more beautiful than Endymion by the English ‘Symbolist’ artist George Frederick Watts? Through the subtle contrasts of color and the piece’s form, he made a simple image of two entwined lovers visually fascinating. He captures the narrative of the drama at its most tender of moments. The torsos of the two figures and the circular shape they create has an impact on how we view the painting. We either absorb the whole piece as shape and color, or instead trace the outline of the bodies in search of the finer details.

Endymion by George Frederick Watts

The narrative of the painting allows us into the mind of a painter who was raised a staunch Christian. He chose, however, to focus his art on Homeric traditions of Greek legend rather than on the Hebraic traditions of the Bible.

Watts was born and lived within walking distance of the eventual founding-place of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Gower Street, London. His art was quite different from theirs though, in terms of his style, and subject matter. Watts was a sickly child. Therefore his father (also named George) opted to home-school him. George senior brought up his son in a heavily Christian environment. Although his son was more intrigued by the Greek texts of Homer in The Odyssey and The Iliad. The narrative aspect to Endymion shows Watt’s fascination with the ancient Gods rather than the biblical stories he grew up with. His upbringing weakened rather than strengthened his faith. He became absorbed in these Greek legends.

The title of Watts’ painting refers to a shepherd who becomes the object of affection for the moon goddess Selene. She then begs her father, Zeus, to make Endymion immortal so that they can remain together for eternity…

…these things are always complicated.

The eventual trade off is that Endymion is made immortal but is eternally asleep. Selene visits him night after night in a cave on Mount Latmus, so she can gaze upon his forever-undiminished beauty.

Watt’s greatest achievement, surely, is in managing to capture in a single snapshot the scene that has already taken me eighty-ish words to try to explain. He encodes so much information into such apparently simple visual terms. John Keats’ attempt is somewhat better put than mine as he addresses the allegory in poetry. He focuses on the passing of time and a yearning for it to stand still in moments of beauty.

(His

final four lines)

We have imagined for the mighty dead;

All lovely tales that we have heard or read:

An endless fountain of immortal drink,

Pouring unto us from the heaven’s brink.John Keats

Keats’ poem focuses on the contrasts of immortality and mortality. In some sections using the passing of the seasons to portray both time moving forwards and turning in a cycle. In some ways this helps us to understand why Watts has created the circle out of the two torsos. It is to emulate the cycles referred to in Keats’ poem. Just as the seasons pass through the year only to repeat, our eye is drawn around the canvas; from their faces, to his torso, to her gown, and to her revealed chest, and then back around again. In the bottom corner is his dog who will inevitably grow old and pass away. Endymion will remain undiminished for the eyes of the moonlit goddess Selene.

G. F. Watt’s (1817-1904) painting was created in the same era as the English Pre-Raphaelite movement (1848-). At this time artists such as Hunt, Millais, and Rossetti created art that rejected conventional Western European styles. They believed that the influence of the Italian master, Raphael and his disciples, should not dominate art so heavily. They instead favored techniques from before the Italian Renaissance.

The Pre-Raphaelites also rejected the habits of other artists of the time. One such group was the Impressionists in Paris who had moved away from the detailed recreation of scenes towards more subjective interpretations. The Pre-Raphaelites held an almost opposite aim in their art. The Impressionists, such as Monet, Renoir (watch Pierre-Auguste Renoir painting!), and Degas, wanted to “gloss over” the intricacies, in favor of highlighting color contrasts and the play of light. The Pre-Raphaelites felt that the beauty was in the details. Their paintings were shimmering images of poetry, beautiful moments from literature, and biblical scriptures. Like many European artists at the time, the Pre-Raphaelites were influenced by Japanese artists. These artists created images with unusual viewing points, or ‘point of audition’. The use of this effect immerses the viewer in the scene as though they are there themselves.

When I was younger it felt like there was a print of Millais’ Ophelia (1851-52) in nearly every old aunt or grandma’s house. Such is the importance of the Pre-Raphaelites in British culture. Still, viewed with fresh eyes, the paintings are beautiful and distinctive. They certainly deserve the merit they receive.

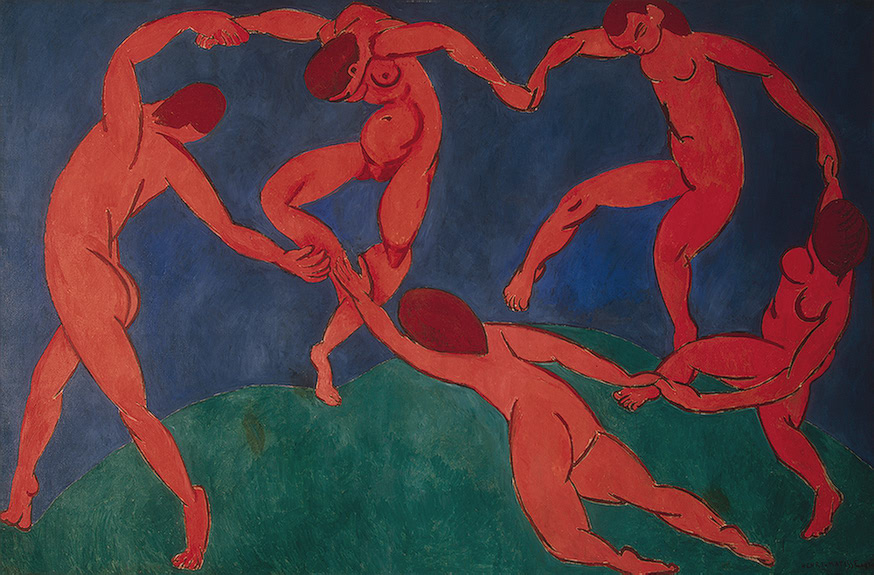

Endymion succeeds on a number of levels. Firstly in portraying the complexity of a narrative through a still image. Also in using a circle, created by two bodies to imply both stasis and movement. This is comparable to a slightly later painting by the French artist, Matisse. He wanted to create a feeling of motion in his artworks. One such example is the painting Dance (1910). In it he uses the forms of his tribal dancers in such a way that we know the direction of their movement. They whirl themselves in a circular motion, not dissimilar to the English children’s game of “ring o’ roses”.

Watts was not a Pre-Raphaelite, instead he became associated with the Symbolist movement. Not least it seems because, like every movement during the 19th century, his style needed to have an “ist” or “ism” on the end!

Watts’ style of painting is not unlike the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in appearance, with his emphasis on detail and craft. Their paintings were often a little more conservative though. One example is Apple Blossoms (1856, above) by Millais. If we compare a piece like Fata Morgana (1865, below) with the figures in Apple Blossoms we can see the differences in subject matter and how it is handled. However there are similarities. These include their use of light and shade, the folds of the fabric, and the texture of the skin tones. The core technique in Apple Blossom barely regards what might have been considered esoteric techniques such as vanishing point or proportioning. In Endymion, with the circle of the bodies, and Fata Morgana, with the voyeuristic relationship between the two main characters, we see the mechanisms of the painter and his Symbolist style. While there is more detail in the Millais painting, there is perhaps more we can learn from Watts’. It isn’t better, just a more interactive experience.

So Watt’s Endymion is poetic, a symbol of both the passing of time and of stasis, repetition and recycling. His technique of capturing the figures and forms in his paintings is of the highest standard. It is comparable with his Victorian age contemporaries the Pre-Raphaelites. But the importance that Watts places on methodology is comparable with the Impressionists and even the Modernists of the early twentieth century. Beautiful and progressive… poetry!