The Evolution of Art During the Fall of Rome

The Fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE was a pivotal moment in history, signifying the end of a dominant civilization that had reigned...

Maya M. Tola 16 October 2023

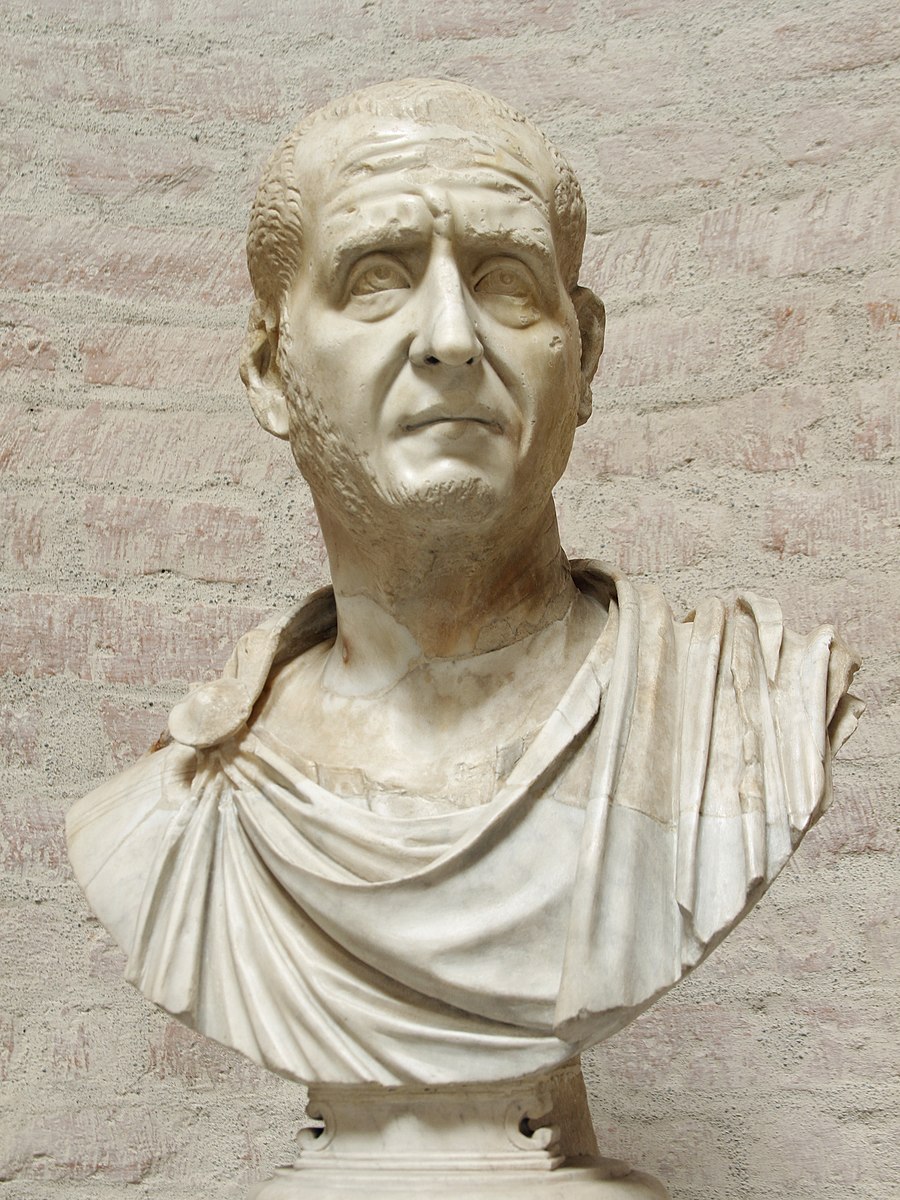

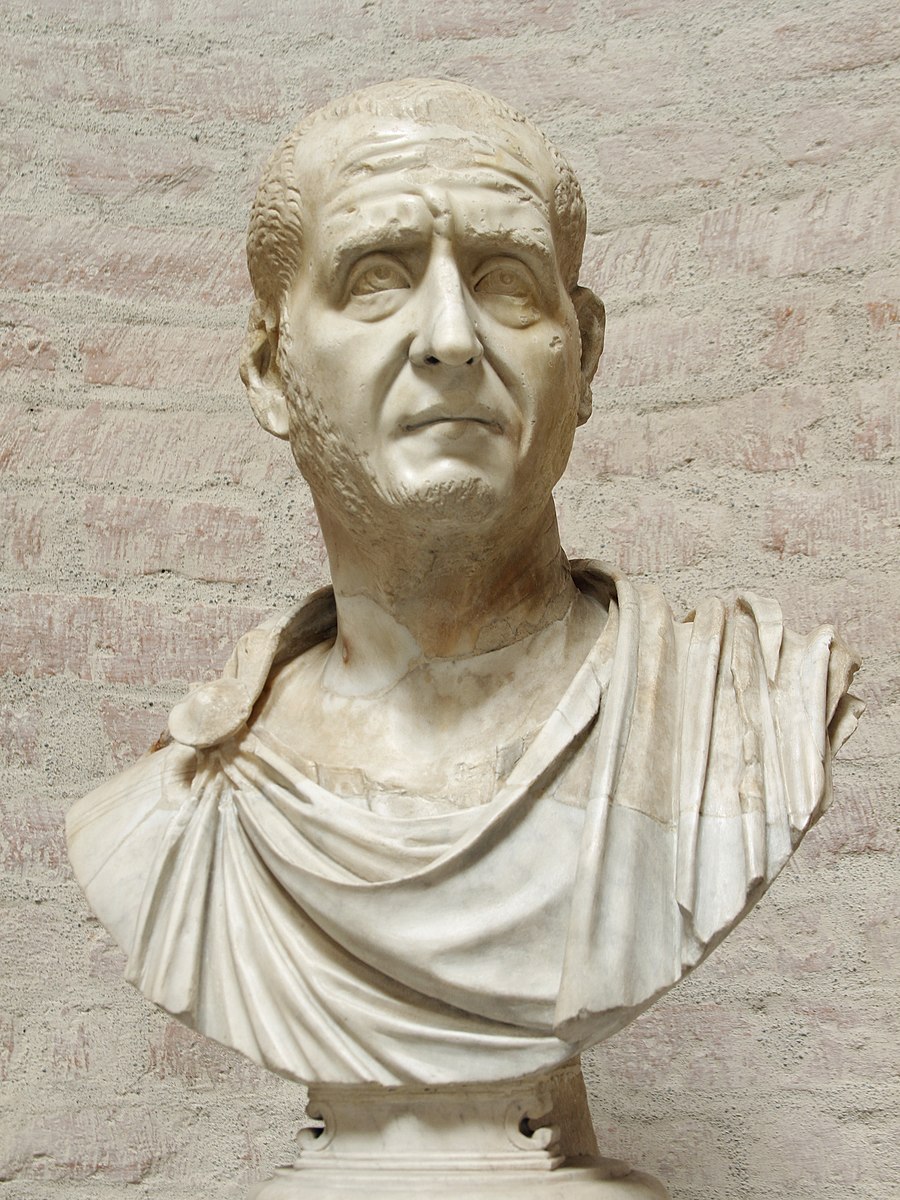

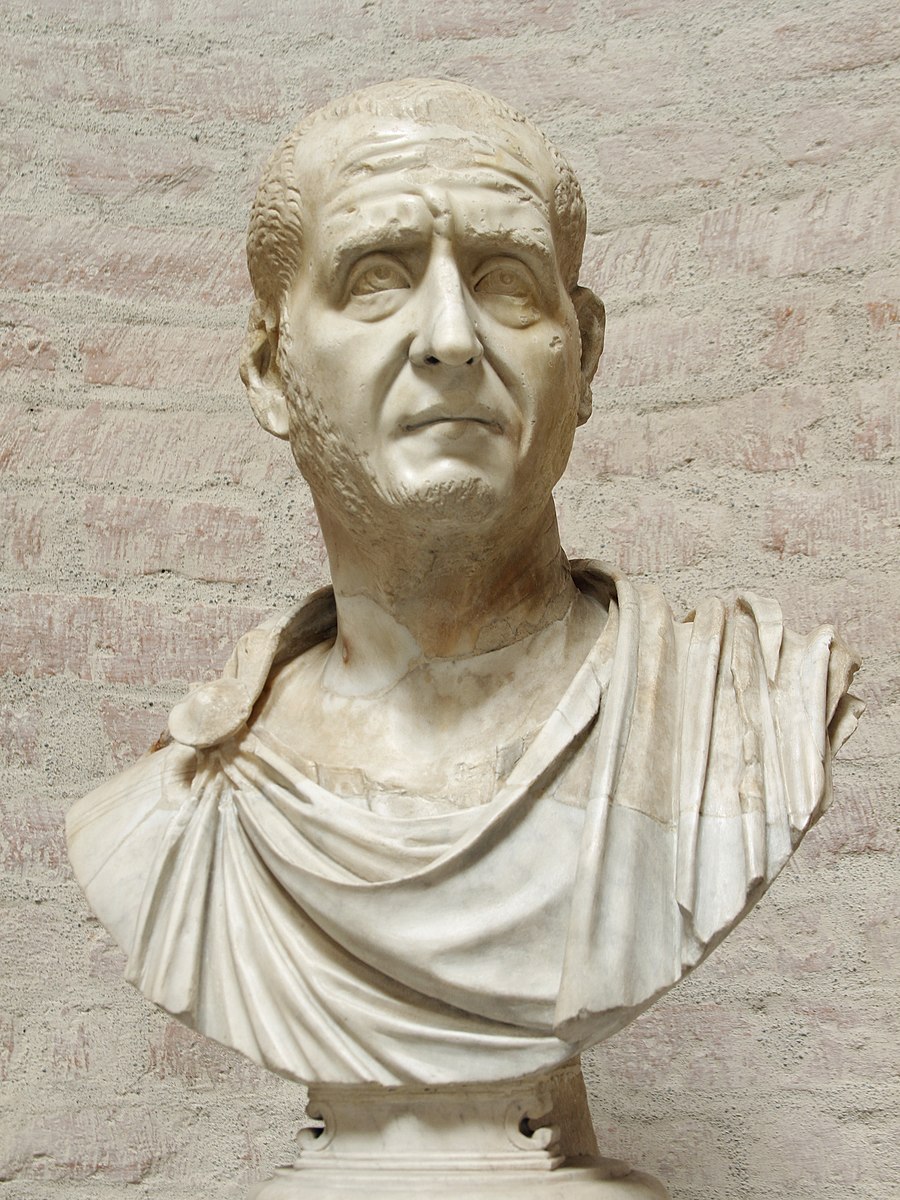

The turmoil of Rome’s decline in the 3rd century enclosed the 21-month reign of Decius. His tenure as emperor was not exceptionally short for the period, plagued as it was by wars both foreign and civil, but its notable features include the tragic outcome of the leader’s character and an ignominious end. Only one marble image of Decius remains. Read the story of the Bust of Decius.

While sculptures of easily identifiable figures from this era are scarce, coins are not; the Romans were prolific on a scale not to be equaled until the Industrial Revolution at producing minted money, a distinction reached via slave or ex-slave labor. Most coins bore the portrait of the emperor, a man few metallurgical engravers would have seen up close because of their low social status and the emperor’s frequent absence from the capital. These profiles accordingly vary widely in details, yet a visual pattern quickly emerges within each reign, making most emperors of this epoch instantly recognizable. Later in the century, stylistic trends favored homogenizing portraits.

Occasionally the artist manages, intentionally or not, to transcend a mere sketch and captures glimmers of psychology more in accordance with the great Renaissance painters. This can be said to be true on an antoninianus (a common silver alloy coin) from the brief rule of Decius.

His age, probably approaching 60 at the time, is apparent in the receding hairline and creased face. It was an advanced attainment for the ancient world, reached after a lifetime of high office in the Senate as consul, probably a governor of provinces according to inscriptions, and prefect of the city of Rome for the emperor Philip. His resume demonstrated his willingness to stake bold positions, as when counseling Philip not to abdicate when beset by usurpers in distant provinces, men whose fickle military backing he knew would soon fold. This would prove a supreme irony considering his own destiny.

A provincial by birth, yet of a prominent family with marital connections, Decius looked to history for guidance – a Roman trademark. For their culture, the glory days were always some earlier era of conquest, triumph, or patriotism exemplified by acts of specific leaders. Thus Decius issued a series of coins bearing portraits of many predecessors as quasi-divinities worthy of homage. Not among them was Philip, for whom he took the field as general, only to be acclaimed as emperor by his own men, a promotion that had to be accepted when imposed. One battle near Verona in CE 249 settled the question, and Decius’ former boss exited by the sword.

Internecine wars, though, were commonplace. It was Decius’ decisions after assuming the throne that shape our memory of him. Aware of his position’s precariousness, he emulated the traditional Roman trait of piety for confidence, an aura of which the coin’s engraver seemed to have transmitted. Decius looks lightly upward in expectation of reward for his dutiful service both material and spiritual, the latter requiring offerings (however simple, sometimes burning incense).

He demanded the same publicly of everyone save the Jews – a concession long predating him – but exempted no Christians. For conservative Romans, that religion was little more than a superstition, and one with heavy political overtones at that. The sect even had an administrative structure with an authoritative leader, the pope, right there in Rome. It is no surprise such a figure was viewed as antagonistic, and Pope Urban was martyred in 250. More paranoid was the harsh enforcement of the sacrifice order (with written confirmation, on pain of imprisonment or death) throughout the empire. Here Decius’ violence betrays anxiety just behind the portrait’s wide-eyed gaze.

The persecution would be remembered for centuries as cruel and was the subject of a medieval Italian painting adopting contemporaneous attire in the habit of the period. This vision of Decius was likely entirely imagined by the artist.

Yet the vaunted barbarians were at the gate, quite literally in the case of cities such as Philippopolis and Nicopolis ad Istrum in modern Bulgaria. The Goths, with their sublimely named King Kniva, wanted loot and knew the Roman interior was the place to find it, dramatically crossing the frozen Danube to pillage. No emperor could avoid this fundamental and often personal task of national defense. Mindful of both his age and fateful mission, Decius raised his sons to high rank (including one also at arms to co-emperor) during arduous campaigns to expel the invaders. The honorific name Trajan bestowed on him after the fantastically successful emperor of CE 98-117, would have to be earned. Clearly, Decius believed in the political system through which he had risen, and a slight air of smugness is detectable in the portrait’s smile.

But one loss in war can negate many gains. Decius’ successes, including some in battles against Kniva, are now remembered by specialist historians. Meanwhile, the events of Abrittus, the site of the decisive clash (again in Bulgaria), dominate his biography. There his elder son became a casualty in the Gothic trap, leading to the revealing quote from his father in a vain attempt to rally the troops: “The death of one soldier is of little significance to the republic.” While we can’t know the exact phrase, or even if it was uttered at all, this line would be in keeping with the emperor’s belief that the state requires sacrifice.

The final word in that declaration reveals a further quality in the portrait; much as the Romans perpetuated the fiction that their military dictatorship was a republic and its leader merely a princeps (first citizen), Decius had convinced himself that his fidelity to the Rome of self-constructed tradition would carry society, if not him, through the crisis. After his son fell in battle Decius followed, the first emperor to perish in arms against an invader, and the last until 378. Abrittus was the military disaster of the century for Rome.

Historians of the Enlightenment, persuaded by Decius’ evident principles, whitewashed this catastrophe as being the result of his treacherous lieutenant and successor while coloring his rebellious accession as reluctant. What is certain is that Rome remained tormented by Germanic tribes for twenty years longer in that wave of hostilities alone, and the persecutions were unpersuasive to Christians, compelling a follow-up under Decius’ colleague Valerian. In 312 Constantine made the upstart religion official, contravening centuries of efforts to eradicate it.

How exactly one reads self-deception on a face might have been beyond the divination of our engraver, but he hinted at it nonetheless, showing more perspicacity than Decius managed in discerning what his empire needed for success. This is the story of the Bust of Decius.

Author’s bio

Michael Keelan has studied Roman coins and their art since the age of thirteen. He works in several fields of classical music, having been a violinist in many orchestras and a faculty member at numerous Midwestern institutions.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!