Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

3 February 2025 min Read

Anthony van Dyck was a Flemish painter born in Antwerp (then Spanish Netherlands, now Belgium) in 1599 and passed away in London in 1641. From 1621 to 1627, he stayed in Italy, where he was employed with commissions and studied the works of the great masters, particularly the Venetian painter Titian. While he spent most of his time in Genoa, he also visited other cities, such as Rome, Venice, Padua, Mantua, Milan, Turin, and Palermo. During his visit to Palermo in 1624, he drew a sketch that might have served as a study for a painted portrait of the Italian painter Sofonisba Anguissola. Here, we tell the story of this portrait.

Sofonisba Anguissola was a late Renaissance Italian painter who was born in Cremona around 1532 and passed away in Palermo in 1625. She worked in the court of Philip II of Spain and established an international reputation for her ability to paint portraits. At a time when women were not accepted as apprentices in the workshops of artists, most female painters came from families where the father was a painter. Sofonisba Anguissola was an exception to this rule.

She studied with painters Bernardino Campi and Bernardino Gatti and, according to a letter from her father, now found at the Buonarroti Archives in Florence, she was held in high esteem by Michelangelo. Giorgio Vasari, known for his biographies of many Renaissance artists, wrote in his Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects that she had not only learned to draw, paint, and copy from nature and from the works of other artists but also produced beautiful paintings of her own.

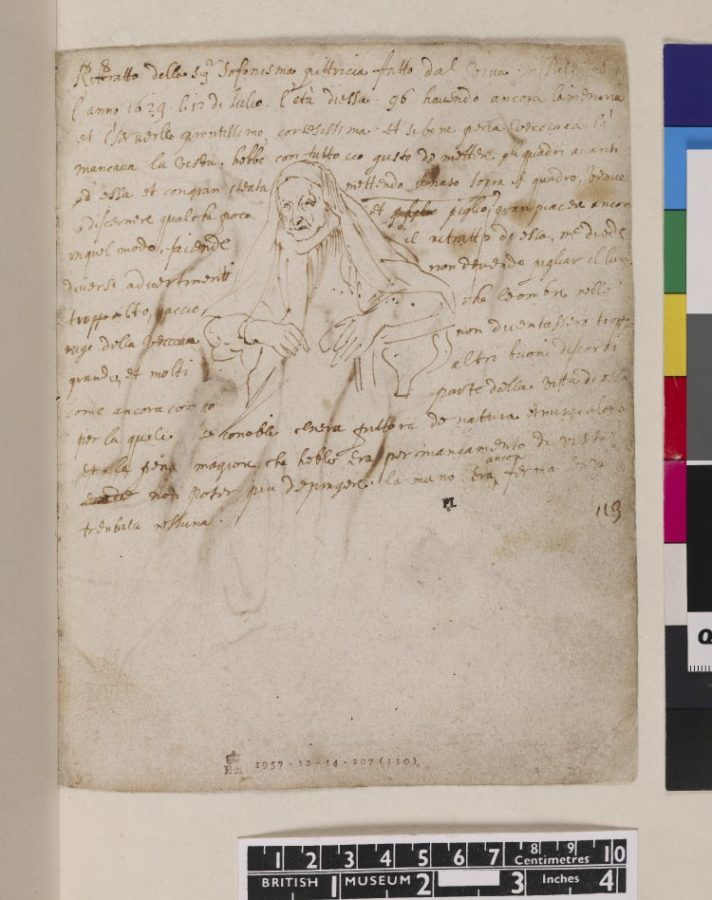

Such is the fame of the woman that the 25-year-old Anthony van Dyck visited in Palermo on the 12th of July 1624. His notes on the visit and the sketch that he made of her are found in his Italian Sketchbook, now at the British Museum. By the time of the visit, Sofonisba Anguissola was an aged woman. Van Dyck believed her to be 96 years old. Now we know that she was 92 and died the following year. Therefore, this portrait is one of her last ones, along with Sofonisba Anguissola on Her Deathbed, painted around 1625.

Despite her old age, she was still lucid and her hands did not tremble. However, she could no longer paint due to loss of sight, which must have been a pity for her and her visitor. Nonetheless, the visit proved to be useful for the young Flemish painter. As he notes, she was courteous and had a good memory. She told him about her life and, as he was drawing her portrait, gave him some advice on the use of light. A feeling of admiration is evident in Van Dyck’s text.

More details on the sketchbook, including an image of the sketch itself as well as the full text of the notes in Italian and an English translation, can be found in Lionel Cust’s A Description of the Sketch-Book by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, used by him in Italy, 1621-1627, preserved in the collection of the Duke of Devonshire, K. G. at Chatsworth.

The painted portrait closely resembles the drawing in Van Dyck’s Italian Sketchbook. It is an oil painting on panel measuring 42 x 33, 5 cm. Sofonisba Anguissola is represented wearing a black dress and a white veil over her head.

The painting is found at Knole, a country house and former archiepiscopal palace located in Kent, England. Knole was a property of the Sackville family since 1603. In 1946, it was gifted to the National Trust and is now open to the public. However, Robert Bertrand Sackville-West, the 7th Baron Sackville, remains its guardian. How the painting arrived there is somehow mysterious. According to the information recorded by the National Trust and the Netherlands Institute for Art History, it was possibly brought by Arabella Diana Cope (1767–1825), wife of John Sackville and 3rd Duchess of Dorset. However, it was initially mistaken for a portrait of Catherine Fitzgerald, Countess of Desmond.

In 2012, the portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola was accepted by the British government in lieu of the Inheritance Tax and allocated to the National Trust. It is now on display in the billiard room of the house, where it can be admired along with a portrait of Caterina Cornaro painted in the manner of Titian. More details on Knole’s portraits are found on the website of the National Trust.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!