5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Let us embark on a journey through the course of art history with twelve significant portraits everybody should definitely know!

The human need to capture its likeness comes with the birth of civilization, making portraiture one of the oldest art forms. We can find the origins of the portrait in Ancient Greece, where important men were immortalized in sculpture. The origins of the painted portrait can be found in Roman Egypt and the Fayum portraits. In Western Europe, reverence of the Greco-Roman civilization and its values sparked the Renaissance. It also led to the resurgence of the individual portrait. However, a portrait is not simply the recording of someone’s appearance. The sitter must be distinctly identifiable, and the artist needs to express the individual identity of their model.

For years, this painting was known as the Arnolfini wedding portrait: nowadays we are not sure if a wedding is taking place. The prevailing theory is that it is a double portrait of wealthy Italian merchant Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife, set in Bruges in the 15th century. Everything in the painting strives to demonstrate the couple’s wealth, from their elegant clothing to the oranges just behind the man on the windowsill. Oranges were overly expensive at that time. The woman’s bulky gown led many to believe that she was pregnant. However, we know from other representations at that time that these gowns were fashionable. The little dog is a symbol of loyalty. The most striking element on the canvas is the mirror between the couple, in which we can see the reflection of two guests who are being greeted by the couple.

Probably the most famous painting in the world, Mona Lisa continues to smile mysteriously throughout the ages. This is Lisa Gherardini, wife of a Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo, hence her other name La Gioconda. Leonardo (1452-1519) painted her in a half length portrait, with a three quarter view. She is sitting in chair which is placed in front of a loggia, a balcony usually supported with arches and columns. There is a landscape in the background. The mysteries that surround the painting are many, but part of her allure is Leonardo’s mastery in capturing not only the features of the woman, but her essence. Here you can find more on Mona Lisa’s illnesses!

The church was probably the biggest patron of the Arts during the Renaissance, especially this man Giuliano della Rovere, later Pope Julius II. He commissioned some of the greatest artworks in Western Art, namely the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel and the Raphael Rooms in the Vatican.

Raphael transformed the art of the papal portrait, setting the standard ever since. In the past, popes were usually portrayed kneeling whilst praying. Julius is painted turning slightly away from the artist. He is sitting in a chair looking calm and thoughtful. Along with spiritual power, the papacy held political power and when this portrait was painted, Pope Julius was one of the most powerful men in Europe. This is slightly referenced by his hands which grip the chair forcefully, showing him as a man of action. The acorns in the back of the chair symbolize the della Rovere family, acorns being in their coat of arms. The two crossed keys on the green screen behind the figure, are the symbol of the papacy.

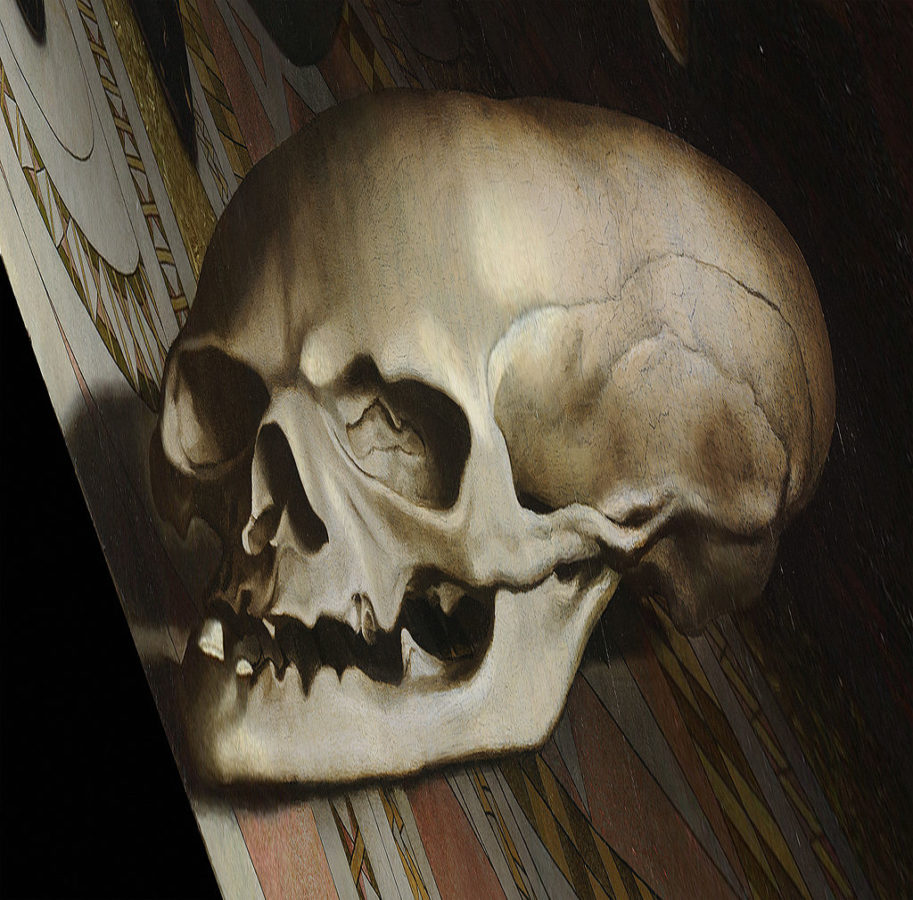

In 1533, Jean de Dinteville (left), the French ambassador to England, commissioned Hans Holbein the Younger (1457-1543) to paint this double portrait. It shows him with his friend Georges de Selve, also an ambassador and clergyman. The two men stand in front of a green curtain with a still life on the table between them. The painting is rich in symbolism. On the top shelf we have objects that relate to astronomy and the measuring of time, things that represent the celestial realm. On the bottom, we have items, which include a lute and a book of hymns, that represent the terrestrial realm.

In the foreground we see an unusual shape. But if we look at an angle we realize that it is actually a foreshortened human skull, a memento mori, meaning a reminder of death.

There is a political and religious aspect to the painting as well. Francis I of France sent De Dinteville to England to keep an eye on Henry VIII. The English king had broken from Rome to marry Anne Boleyn, and as a result caused turmoil all over Europe. The broken string on the lute represents this situation on the canvas.

Group portraits were really popular during the Dutch Golden Age. Many guilds commissioned them to celebrate their most distinguished members and these portraits were then hung in their guildhall. Here we have the company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and his lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburgh, surrounded by sixteen of their men.

Rembrandt (1606-1669) revolutionized this type of portrait by presenting the company in action, in the act of forming up. It was more common at that time to depict the sitters in rows, akin to a contemporary group photograph. Here, the militiamen emerge from shadow into the light. That, along with the artists clever spatial arrangement of his subjects, infuses the painting with energy. On the left we can see a little girl among the men. Attached on her waist band there is a chicken with large claws and a musket, the symbols of the militia company. She is a kind of mascot, an impersonation of the company. Here you can find more on the painting.

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) was one of the most celebrated portraitists of 18th-century England. This portrait of Robert Andrews and his wife Francis Carter was commissioned on the occasion of their wedding in 1748. The newlyweds wanted to commemorate the event and to display their newfound status as owners of a larger estate. Hence Gainsborough placed the couple on the left and showed their grounds on the right. Mr. Andrews stands in a relaxed pose, while Mrs. Andrews sits demurely on a rococo bench. Thus, in this work we have the opportunity to admire a double portrait and a landscape painting at the same time, each element fighting for our attention. On a more bizarre note, a part of the canvas on Mrs. Andrews lap is left blank, with no apparent explanation.

Charles IV of Spain commissioned Bonaparte’s portrait as part of his series of powerful men of Europe. Napoleon crossed the Alps in 1800 in a victorious campaign against the Austrians. The landscape is just a setting for the portrait, Napoleon dominating the entire canvas. He mounts a horse and with a powerful gesture rallies his troops, some of whom can be seen in the background. It is a highly constructed image. Jacques Louis David (1748-1825) wanted to highlight the virtues of the monarch and convey the power Napoleon had at that time. On the left, in the foreground, we see inscribed the names of Hannibal and Charlemagne, two other rulers that crossed the Alps, a mighty task that few had managed.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) is mostly known today for his odalisques. However, during his lifetime he was an acclaimed portrait painter. This is one of his last commissions, a portrait of Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn. Here, the princess poses in an aristocratic and reserved manner. Ingres’ tight brushwork gives the painting an almost photographic quality, managing to capture both the essence of his sitter as well as the texture of her clothing. Without a doubt the most impressive section is the blue dress she is wearing. The satin shines in the light and we can almost anticipate the rustle of the fabric as she moves.

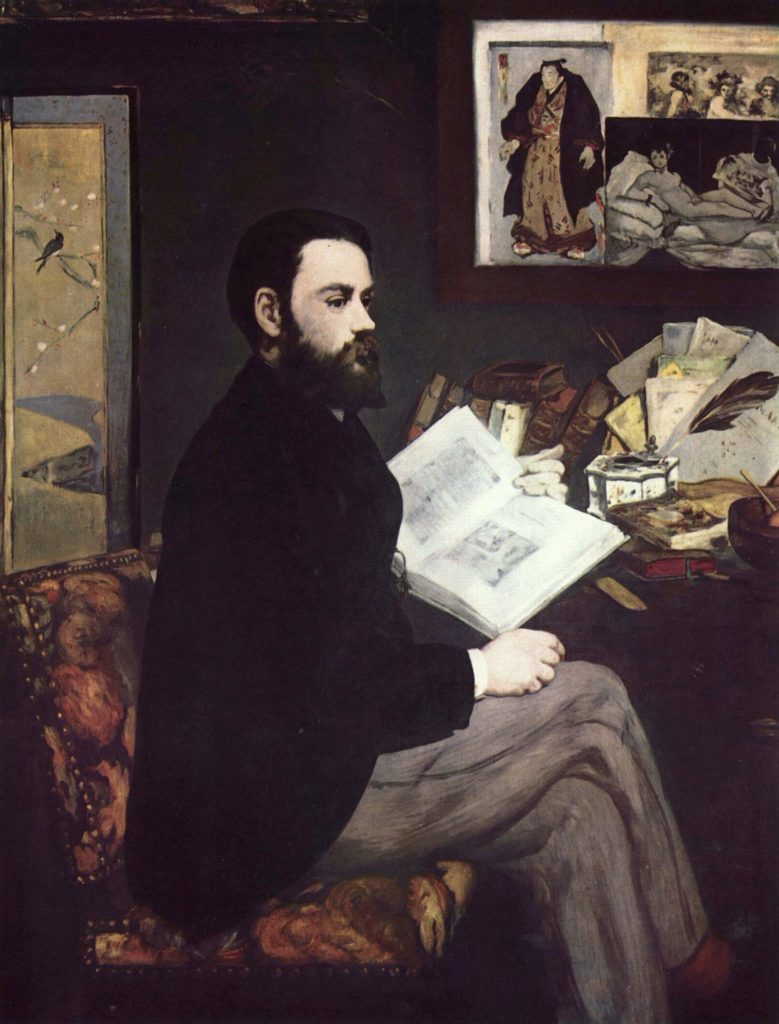

Edouard Manet (1832-1883) painted this portrait to thank the writer, Emile Zola, for supporting him against the official art critics of the time who constantly rejected his work. The article Zola wrote is the blue pamphlet at the left. On the desk there are attributes that illuminate the writer’s character and tastes. We can see a copy of Manet’s Olympia, which Zola considered his greatest work. Above Olympia there is a black and white reproduction of Bacchus by Velazquez which indicates his interest in Spanish painting. Behind Zola there is a Japanese screen. This, along with the Japanese print, demonstrates the impact of Eastern painting on Manet’s art. On the desk, there is a quill and an inkwell symbolizing Zola’s profession.

The portrait is of Madame Pierre Gautreau, a young socialite in 19th-century Paris. John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) portrayed her as a seductive fashionable woman. The painting caused turmoil when it was exhibited in the 1884 salon mainly because of the way she was presented. The gown’s neckline and the right strap of her dress that was slipping from her shoulder, shocked Parisian society. The artist later repainted the strap. Sargent kept the work for over 30 years. He ultimately sold it to the Metropolitan Museum commenting ‘’ I suppose it is the best thing I have done’’. Despite the furore, it cemented his reputation as a portrait painter, and led to a fruitful career in the United States.

The portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer is also known as the Woman in Gold. It was commissioned by her husband Ferdinand a wealthy banker and factory owner. Adele has the unique honor of being the only woman Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) painted twice. In this painting it seems like she emerges from or sinks into the gold. Only her head and hands are painted realistically, conveying a sense of discomfort. Her dress is lost within the numerous patterns on the canvas. It feels like the woman has become one with the gold background, a precious object herself.

Adele died in 1925 leaving the portrait to her husband with the wish that it should be given to the Austrian National Art Gallery after his death. Sadly that didn’t come to pass. Eventually, there was a legal dispute between the Austrian government and Adele’s nephews who had inherited the canvas. Here you can find more on the turbulent history of the painting.

For many centuries, almost every man of means commissioned a portrait to cement his memory into posterity. Painters depicted their personality and also their wealth and status. The art of the portrait was not lost, despite the invention of photography in the late 19th century. It continued to flourish throughout the 20th century in the work of artists like Lucian Freud.

How many Marilyns can you take? Andy Warhol created a series of portraits following the actress’s death in 1962, using a publicity photo from her movie Niagara. The painting consists of two panels, one in color and the other in black and white. Marilyn Monroe was the most iconic star of her era. Consequently she was an ideal subject for the artist to use in order to comment on celebrity culture. Her face looks like a mask, a reference to her highly constructed image as created by the media. Moreover, multiple repetitions were used to show her constant presence in the press.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!