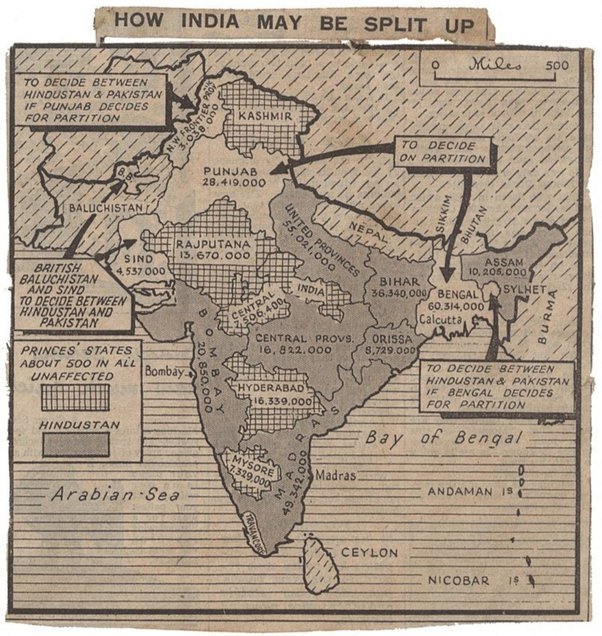

I was drawn to the spittoon, a vessel for expectorate as a carrier for memories. I used antique spittoons from the 1920s, which are relics of the early 20th century, as containers of memory, and hand-engraved maps, names of revolutions, declarations of independence, and treaties onto their exterior. By transforming the spittoon into a memorial rather than a vessel to hide waste, the work counters attempts to obscure the violence of colonialism, while recognizing how knowledge of historical atrocities has been subjugated. While these events are historicized as isolated events, I propose their interconnectedness; the Irish and Indian freedom fighters supported each other as they fought for independence from their British oppressors.