5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

A quick internet search for “the Prodigal Son in art” yields some 13,000,000 results! What makes this 2,000-year-old story so compelling that artists keep returning to it again and again?

The Prodigal Son is one in a series of parables that Jesus shared with his disciples, on the subject of repentance and forgiveness. There are four books of The New Testament devoted entirely to Jesus’ teachings (the four Gospels), and therefore there is considerable overlap in the information in each. However, it is interesting to note that this story only appears in the Gospel of Luke.

A parable is a short story designed to teach an important truth or moral lesson. When Jesus taught this particular parable, he paired it with two others about The Lost Sheep, and The Piece of Silver, both addressing the themes of repentance and return to the fold. The Prodigal Son is the longest parable in this cycle, and begins with a very familiar situation.

“…A certain man had two sons: And the younger of them said to his father, Father, give me the portion of goods that falleth to me. And he divided unto them his living.”

Luke 15:11, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

A prodigal is a person who is wasteful of his or her money or possessions. The story opens when the younger of the two sons asks his father for his share of the inheritance. The title of the tale places the spotlight on the son and his character arc of growth and self-improvement. But, so much can be gleaned by taking time to think about the roles of the other characters in the story, particularly the father, and the older brother.

In The Prodigal Son Receives His Portion of the Inheritance, Murillo invites us into the opening scenes of this timeless story by showing us the son, but also, the father. What kind of father complies with this kind of request? By sharing his inheritance before it was due, the father shows great trust in his son. Whether it was deserved or not, time would tell, and it was certainly a great risk. But, the father still took it.

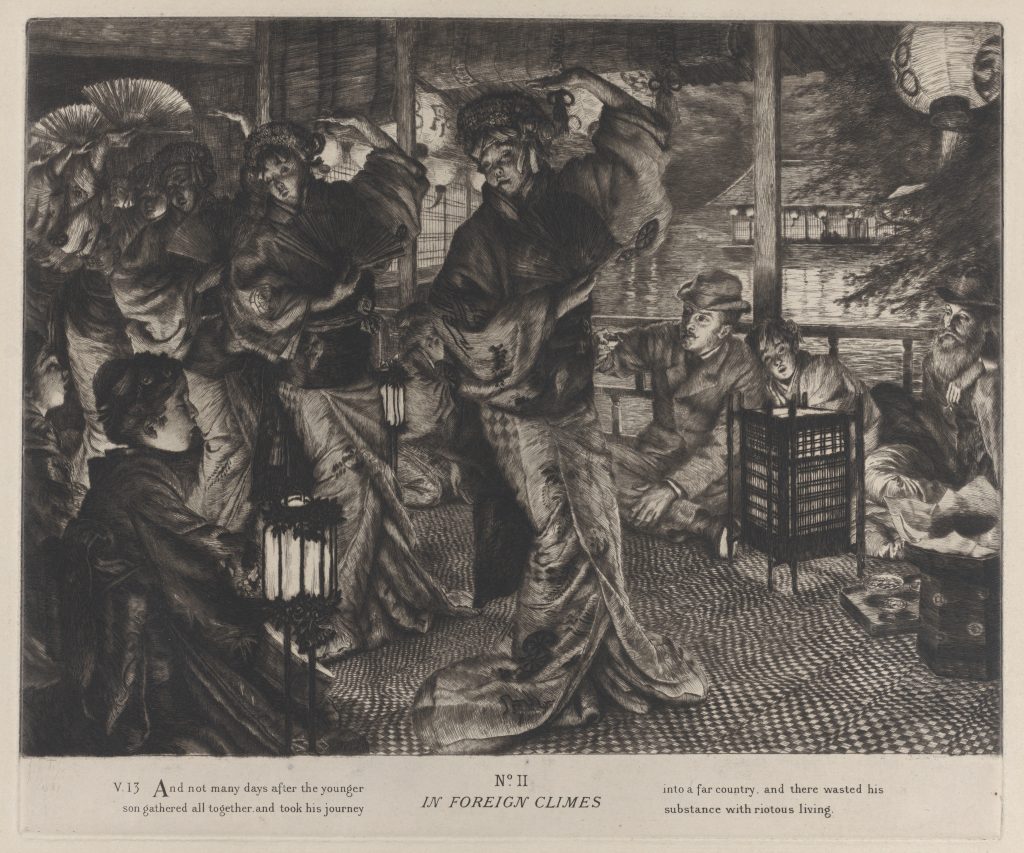

“And not many days after the younger son gathered all together, and took his journey into a far country . . .”

Luke 15: 11-13, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

Here we see the second painting in Murillo’s series about The Prodigal Son, and we receive more context to understand the story. We see the other family members grieving the son’s departure, we see the father, and the older brother. What kind of relationship existed between them? What prompted this young son to leave? Many painters have shown us more climactic moments in the story, yet Murillo places us in the middle of the action from the very beginning. What was he trying to accomplish?

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo was a Spanish painter who created a cycle of six paintings based on this parable for an unknown Sevillian patron. In 1649, plague struck the city of Seville, and within a year a quarter of the population had died. It seems fitting that this story of suffering and redemption would appeal to a patron—and a painter—during this difficult time. Murillo’s cycle is unique because it was the first time this parable was set in Spain, with figures and backgrounds typical of 17th century Seville. The National Gallery of Ireland was set to show all six paintings together for the first time in decades this year, after an extensive restoration project. You can find more information about it here.

“. . . and there wasted his substance with riotous living.”

Luke 15: 11-13, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

James Tissot is another painter who depicted the parable in a series, also representing the story for the contemporary viewer. Interestingly, he did this not only once, or twice, but three times! He completed a series of etchings on laid paper, but he also represented the parable in watercolor, and through oil on canvas.

During the 1880s, Tissot had a religious awakening that led him to create a number of paintings on the life of Christ. His paintings on The Prodigal Son came from this time, and he kept the originals in his possession until his death in 1902.

Rembrandt went beyond representing contemporary life, and inserted himself and his beloved wife, Saskia, into the parable. He did so in this depiction that is also known as The Prodigal Son in the Tavern, or The Prodigal Son in the Brothel. It is possible that Rembrandt just used the parable as a vehicle to paint a secular scene, and give it Biblical underpinnings. Still, it is very interesting that he chose this particular story, and this particular scene! Rembrandt himself would go on to revisit the parable later in his life, as we shall see below.

During his lifetime, Rembrandt painted between 40-50 self-portraits. Rembrandt and Saskia in the Prodigal Son may also have been an excuse to fulfill the high demand for tronies in the Dutch art market.

“And when he had spent all, there arose a mighty famine in that land; and he began to be in want. And he went and joined himself to a citizen of that country; and he sent him into his fields to feed swine. And he would fain have filled his belly with the husks that the swine did eat: and no man gave unto him.”

Luke 15:14-16, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

Return of the Prodigal Son, by Rubens, is a piece with a very interesting history. Earlier in his career, Rubens may have used this Biblical story as a means to practice his landscapes. But, when he died in 1640, he mentioned this piece of 1618 in his will, which implies he still had it! Throughout the years, it changed hands many times, until the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, bought it in 1894.

English painter and sculptor John Macallan Swan established his reputation as an artist with his painting The Prodigal Son. Even though he represented very powerful renderings of the human figure, he became best known for his depictions of wild animals. In this canvas he shows us both, with great skill and emotion. The focus is on the son, but Macallan Swan does not show us his face—he makes us feel his despair, which is heightened when we discover the many forms that make up the background: the swine. He is surrounded by pigs, and entirely alone.

What a far cry this is from the proud, noble, well-dressed son of Murillo’s painting! Or the pleasure-seeking reveler of Rembrandt’s! Where can the prodigal turn to now?

“And when he came to himself, he said, How many hired servants of my father’s have bread enough and to spare, and I perish with hunger! I will arise and go to my father, and will say unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and before thee, And am no more worthy to be called thy son: make me as one of thy hired servants.”

Luke 15:17-19, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

Dürer approaches the parable at the action’s highest point—the moment when the son realizes that if he were back at his father’s house, he would have food and shelter, even if he were one of the servants. What does this tell us about this father, and the family where this boy had come from? What a powerful moment when this lost child realizes that he can come back!

Murillo also shows us the son looking upward into heaven at his moment of awakening. It is interesting to see the visual representation of the parallel between returning to one’s parent, and returning to the fold of God.

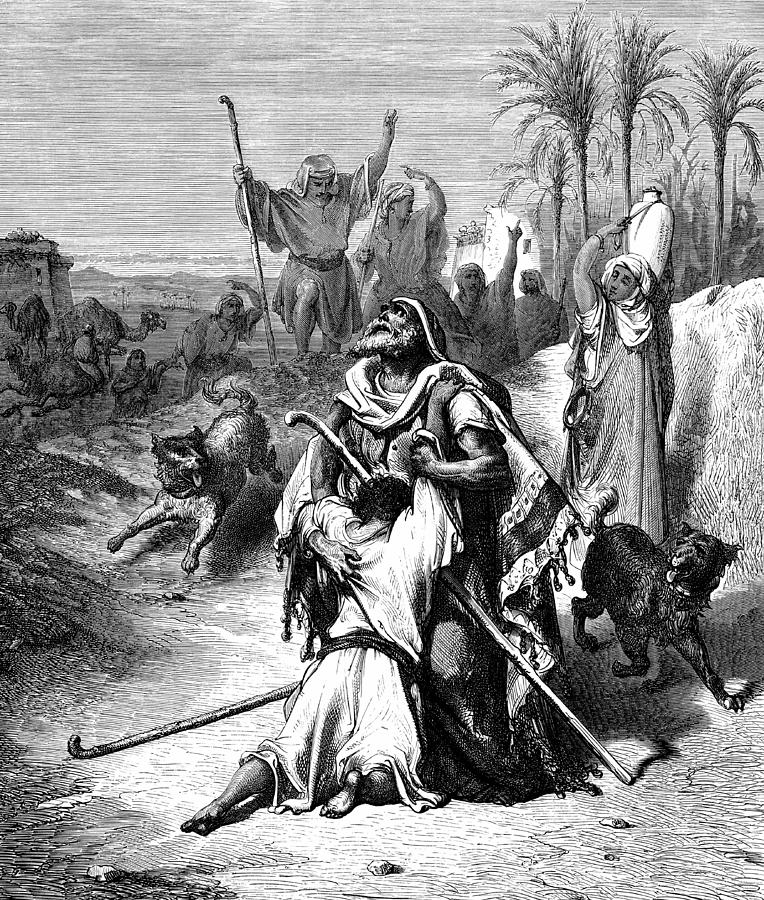

“And he arose, and came to his father. But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him. And the son said unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son. But the father said to his servants, Bring forth the best robe, and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet: And bring hither the fatted calf, and kill it; and let us eat, and be merry For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found. And they began to be merry.”

Luke 15:20-24, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

Gustave Doré was a French artist, illustrator, and printmaker. He designed a series of wood engravings for the 1843 French translation of the Vulgate Bible, also known as the Bible of Tours. This interpretation of the prodigal’s reunion with his father belongs to that series, and captures the essence of the poignant scene perfectly. The father and the son are the focal point of this work, and in the lines of their bodies, in the father’s expression, we can feel so much emotion. But Doré gives us more—the welcoming dogs, and the entourage of household members, all gathering to receive this young son.

The Return of the Prodigal Son is the last great work that Charles Gleyre completed before his death in 1874. In his interpretation, we can see not only the son being welcomed by his father, but by other members of the household who receive him with open arms. This painting offers a great contrast between the two main figures. The well-dressed, fair lady in the painting is ready to embrace the prodigal, even though he is presumably filthy and has lost everything—a great part of the family’s money, his own dignity, and maybe even the family honor. Yet, all of this doesn’t matter because he is back! A friendly, loyal dog, is licking him—what better sign of welcome?

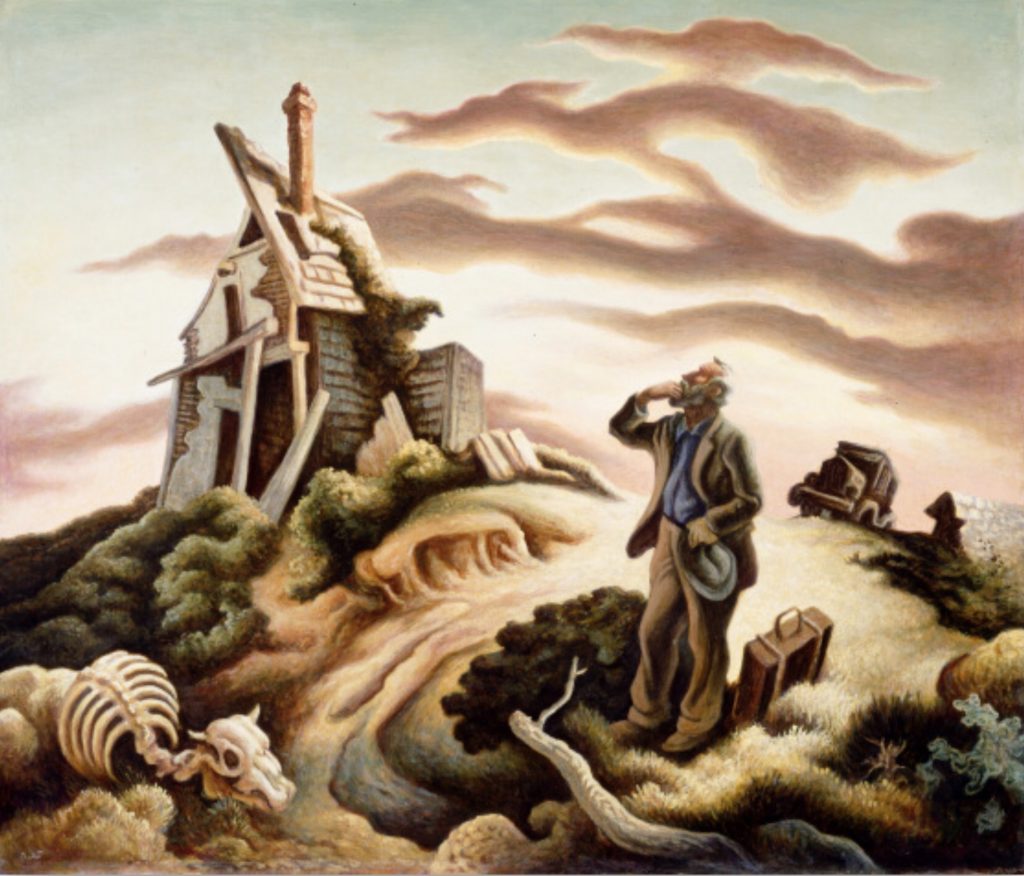

American artist Thomas Hart Benton gives us a very different take on the homecoming. During the 1930s, the American and Canadian prairies were affected by a severe period of dust storms and drought, known as the Dust-bowl. Thousands of families were forced to abandon their farms because they could not grow crops, therefore they could not pay their mortgages. This period coincided with the Great Depression, and it was a miserable, hopeless time that fit the arc of The Prodigal Son very well. In Thomas Hart’s interpretation, however, the prodigal has returned too late—the homestead is in ruins, the animals have died, and the family is gone. Was this caused by his reckless behavior, or by circumstances beyond anyone’s control?

“Now his elder son was in the field: and as he came and drew nigh to the house, he heard music and dancing. And he called one of the servants, and asked what these things meant. And he said unto him, Thy brother is come; and thy father hath killed the fatted calf, because he hath received him safe and sound. And he was angry, and would not go in: therefore came his father out, and entreated him.”

Luke 15:25-28, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

“And he answering said to his father, Lo, these many years do I serve thee, neither transgressed I at any time thy commandment: and yet thou never gavest me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends: Bus as soon as this thy son was come, which hath devoured thy living with harlots, thou hast killed for him the fatted calf. And he said unto him, Son, thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine. It was meet that we should make merry, and be glad: for this thy brother was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found.”

Luke 15:29-32, The King James Bible. Bible Hub.

The focus of Michel Martin Drolling’s interpretation is on the welcome. But, he also shows us the unintended results of the father’s actions toward his repentant son, in the form of the older brother. We see him to the right of the painting, in the shadows, watching everything from afar, unable to join in the rejoicing.

Rembrandt revisited this parable just months before his death. Remember how, in his youth, he had painted himself into the story? We had seen him happy, partying, while everything was going well. Here, towards the end of his life, he gives us quite a different side to the parable. We see the repentant son, and we can hardly recognize him after all he has experienced. We see the older son—this son who had ever done everything he had been asked to do, and who was also in need of repentance. But, Rembrandt shows us, quite visually, that the light falls on him, also. He, too, is eventually redeemed.

It is interesting that Rembrandt produced such a masterpiece for his own pleasure—this was not a commissioned work. What did this story mean to him? What can it mean to us? Regardless of where we see ourselves in the parable—as the Father, the household, the older brother, the prodigal son—the timeless message of hope after trials is one that can touch us today, as it touched all the many artists who painted all the prodigal sons.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!