An innocent visit to the Whitney Museum of American Art in the West Village of New York City on Sunday, December 9, turned into something more. The smell of burning sage was powerfully oppressive. The New York City fire department was called to restore order. The first floor of the Andy Warhol— From A to B and Back Again retrospective was temporarily closed for security reasons.

Protest at the Witney Museum of American Art. Video by Howard Schwartz

A crowd of protestors, armed with bongo drums, banners, and a powerful message congregated in front of the museum’s entrance. They were members of an activist group, ‘Decolonize This Place.’ Their ire was directed at the vice chairman of the Whitney, Warren Kanders. According to the New York Daily News, “’Decolonize This Place’ called for the protest against Warren Kanders nearly a week after 100 museum employees signed a letter asking the Whitney take action against him.” Kanders has “ties to a company that manufactures tear gas being used on refugees at the U.S. border with Mexico.”

The protest achieved many of its goals. This political issue is now more well known to the general public.

This is not the first time the Whitney Museum has been the target of demonstrators. In July 2018, protesters from ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) were up in arms over an exhibition, ‘David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night.’ Their issue was that the AIDS epidemic is a current concern, and referring to the epidemic in the past tense gives a false impression that the issue is resolved and no more work needs to be done.

The Andy Warhol exhibition, even in the midst of the chaos around it, was a powerful and moving tribute to an artist who did so much, even though he died so young. Works of art by Warhol were on three different floors. Many of the pieces were huge, much larger than expected, and the rooms they were shown in were even larger and more spacious. When I got off the elevator on the fifth floor, I had no idea which way to walk.

A room near the entrance was showing video clips. One clip was a silent screen test for Ethel Scull, who was looking straight into the camera. Only her head was visible. Her 4:30 minute screen test was noteworthy for a neutral facial expression and her blinking eyes. My mind wandered. This was followed by another silent screen test, this one for Edie Sedgwick, who seductively gazes into the camera, moving her lips and neck as well as blinking her eyes.

‘Self-Portrait,’ from 1966, made with acrylic, silkscreen ink, and graphite on linen, is divided into three or four colors. Its power comes from its graphic simplicity, and its air of mystery. Warhol’s left eye is shrouded in shadow, making it difficult for the viewer to establish intimate contact with him. The viewer can only observe.

Selections from ‘Flash—November 22, 1963’ transported me back in time to the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination. Three of the framed images were nothing but text, but that text, in its simplicity, set the mood for the rest of the piece. When I read that “President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed today as he rode in a motorcade through downtown Dallas,” I thought of Walter Cronkite delivering the news on CBS television. When I read that“Lee Harvey Oswald, accused slayer of President Kennedy, was shot and seriously wounded in the basement of Dallas police headquarters today,” I recalled seeing the shooting on live television and how shocking it was.

Warhol’s fascination with the Kennedy assassination, as well as with other morbid topics, is ironic because, as the exhibition notes, “on June 3, 1968, Warhol was shot multiple times by the radical feminist author Valerie Solanas, who had appeared in two of Warhol’s films.” The difference between what happened to Warhol and what happened to John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. is that Warhol, after “numerous surgeries and a lengthy convalescence,” was able to survive. The 1960s, and 1968 in particular, was a dangerous time in American history.

Andy Warhol was able to accomplish remarkable things as an artist living in this turbulent environment. As an artist, he was able to recreate a mood, as described above. And more importantly, he was able to put familiar ideas and objects and people in unfamiliar settings, changing the way we see and experience them.

This latter accomplishment is well known; silkscreen images of Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley are both familiar and iconic, even to those with only a passing interest in 20th century American art.‘Nine Jackies,’ from 1964, shows three images of Jackie Kennedy, each repeated three times. Her mood changes from joy to pensiveness to sorrow. I wondered why Warhol chose to repeat his images instead of showing one image for each mood. My speculation is that showing three images instead of one enables Warhol to convey the passage of time, even when nothing is changing. Each repeated image strengthens the impact of the image before it. Each image lingers; as the viewer, I am given time to experience each emotional state. And then suddenly, after three monochromic images of Jackie Kennedy smiling with the innocent joy of youth, the blue color is removed. Jackie Kennedy’s mood abruptly changes as well, and then, after three images of this state of mind, we are abruptly brought back to the blue monochrome with a close up of the First Lady’s pain. I can envision watching a silent movie and feeling the same impact. This collective image moved me far more than I would have expected, and far differently than I would have been moved had I seen each of these photographs in the way they were originally shown in the newspaper.

The exhibition states that “the first image was taken in Dallas just prior to the shooting; the second during his funeral; and the third as Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as president.”

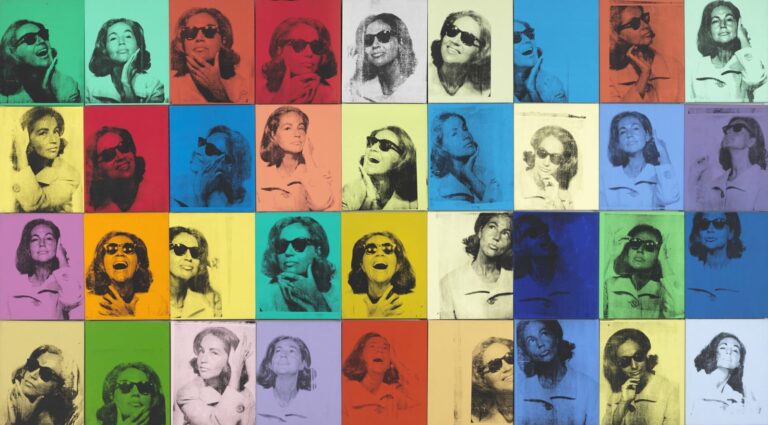

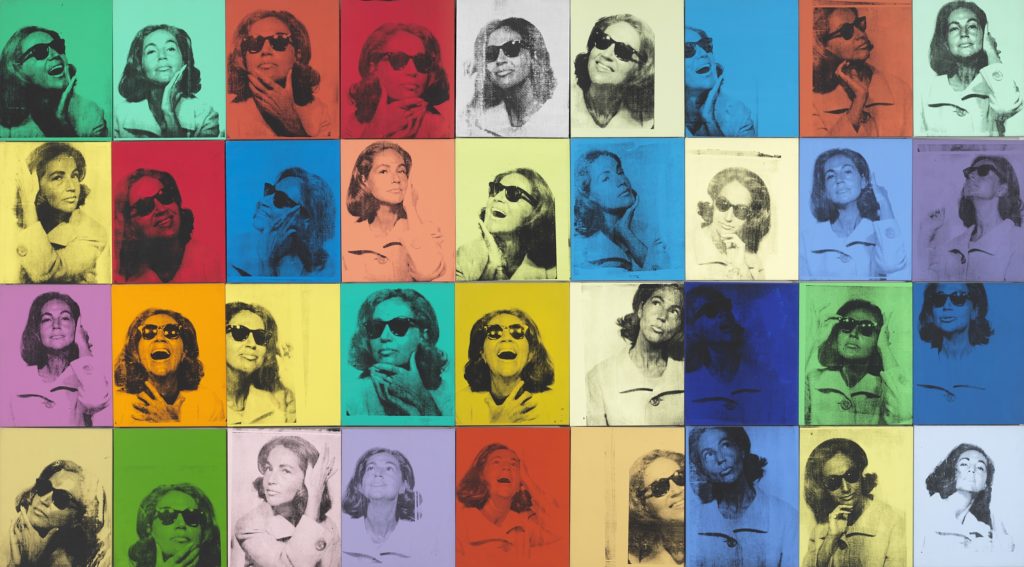

Andy Warhol’s use of color was evident in ‘Ethel Scull 36 Times,’ from 1963. This is the same Ethel Scull who participated in the screen test referred to above. Ms. Scull was an art collector. These 36 panels are described as Warhol’s “first major painting commission.” The photos for this piece were taken in a photo booth on 42nd Street in Times Square. The advantage of photographing Ms. Scull in this manner is that the photos portray her as relaxed and casual. The exhibition describes her as flirtatious. The bright monochromatic backgrounds present these images in an abstract way, reminiscent of a Paul Klée composition. At the same time, the viewer is given the opportunity to get to know Ms. Scull in a way we would have been unable to do otherwise. I am drawn in and can look at these images of Ms. Scull over and over again, never getting bored.

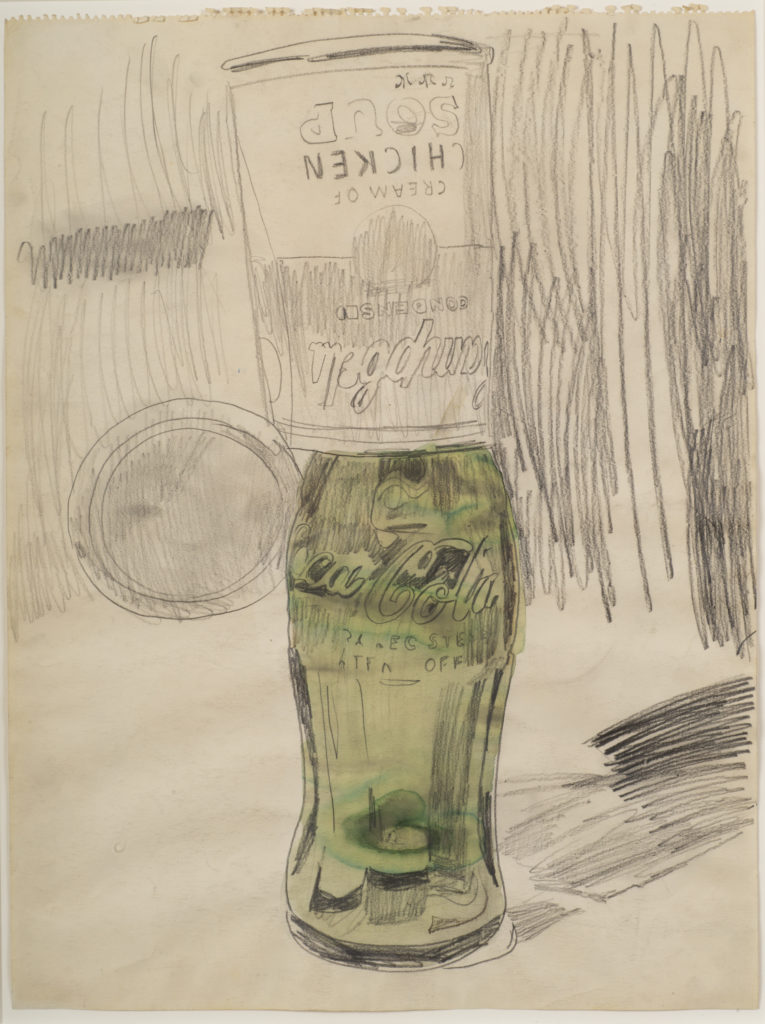

The exhibition explains that “Warhol had painted by hand but imitated the effect of mechanical reproduction. The procedural shift to an actual mechanical process—the silkscreen technique—remains his most crucial breakthrough.”

An example of a “painting by hand” is ‘Before and After[4]’ from 1962. Warhol alters this fascinating image of a woman who has had a nose job by blowing it up in scale. When one shifts one’s gaze from the first image to the second, and then back to the first, the woman’s nose seems to shrink and to grow, over and over again. The larger nose is slumped over, whereas the sleeker, post-surgical nose is pridefully erect. The more I looked back and forth, the more I wondered about this woman. The simplicity of the images and the simplicity of the positive and negative shapes within the images made it easy for me to stay with this painting for much longer than I would have expected.

There is so much more to be said about Andy Warhol and his art. His camouflaged Last Supper is an extraordinary piece that influences the way I think of Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous painting. By making the image so large and obscuring it, I am forced to try to peel away the outer layer of camouflage to see the expressions of the disciples of ‘The Last Supper.’ And the art of Andy Warhol became more abstract in the later years.

This exhibition, which closes on March 31, 2019, is a must-see, with or without the sage. The Whitney does a magnificent job of making Andy Warhol’s celebrity relatively unimportant in the context of this exhibition. Instead, the Whitney focuses on Andy Warhol’s art.

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”0300236980″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/512T2BlJIXuL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”129″]