Summary

- Zenobia was a ruler of Palmyra and is known for her conquests of the ancient Near East.

- The invasion of Egypt waa a turning point in Zenobia’s fortune, as she was eventually defeated and captured by the Romans.

- Harriet Hosmer was one of the greatest 19th-century sculptors. Much like Zenobia, she felt stifled by the limitations imposed on women in the 19th century.

- Hosmer was inspired by the character of Zenobia and spent two years on the creation of the sculpture Zenobia in Chains.

- Her depiction is far from 19th-century canon – depicting a captured woman as a victim, filled with dignity.

The Queen of Palmyra

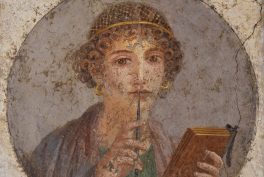

Septimia Zenobia, (or Znwbyā Bat Zabbai in Palmyrene Aramaic) was born in 240 CE in Palmyra in ancient Syria, a vassal state of Rome. The translation of her Aramaic name was “daughter of Zabbai” referring not necessarily to her immediate father, but to an ancestor in her lineage. Zenobia was born into nobility and received an extensive education. It is believed that she was instructed in Greek and Latin and spoke fluent Aramaic and Egyptian.

While her ethnic roots remain undetermined, some historical records indicate that she had Greco-Egyptian ancestry. However, the assertion of Ptolemaic heritage could have very well been political propaganda as Zenobia would go on to claim Cleopatra VII as an ancestor to justify her ultimate conquest of Egypt.

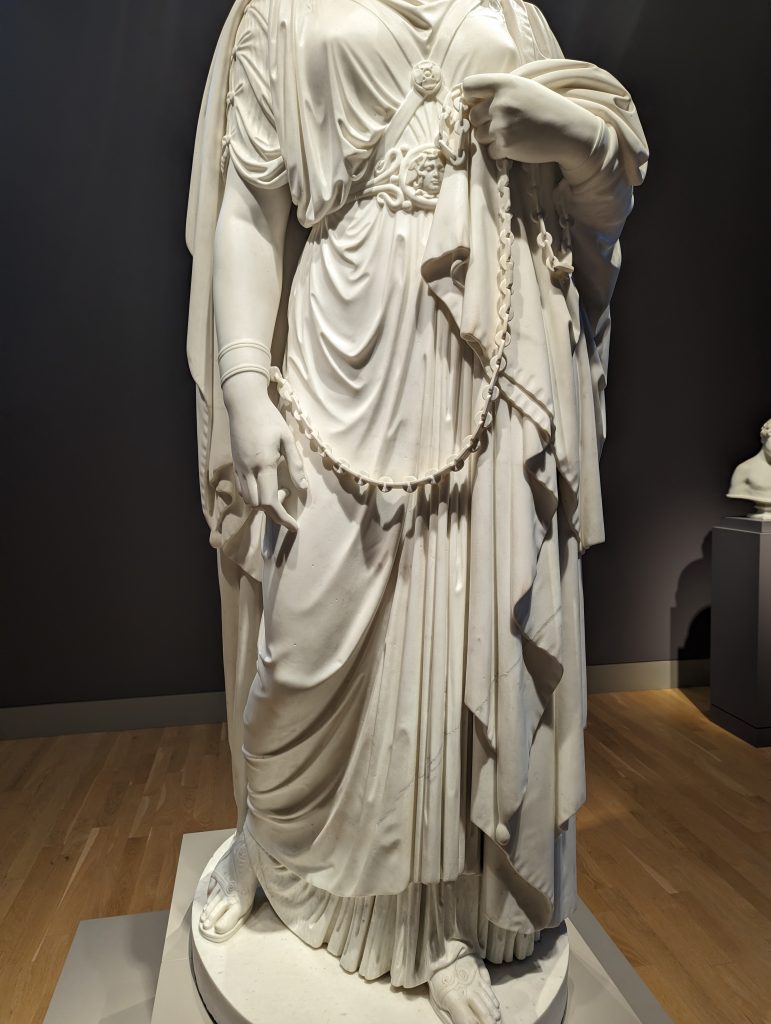

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Zenobia in Chains, ca. 1859, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, USA. Photograph by Maya Tola.

Ascension to the Palmyrene Throne

In the year 258 CE, Zenobia became the second wife of Septimius Odaenathus, the ruler of Palmyra who had been bestowed with the traditional Persian title of “King of Kings”. She gave birth to Wahballat (Vaballathus in Latin, Athenodorus in Greek), the second son of Odaenathus, who ascended to the throne in 267 CE upon the assassination of his father and his older half-brother, Hairan. Vaballathus was appointed as the King of Palmyra and Zenobia became a regent for her minor son.

Although there are many accounts that affirm Zenobia’s role as a regent, there is also evidence from coinage and other records to indicate that she had declared herself as a co-ruler to the Palmyrene empire along with her son.

While her exact designation may be unclear, Zenobia’s incredible military and diplomatic acumen were undisputed. Zenobia spearheaded an ambitious conquest of the ancient Near East during her reign and played a prominent role in the military campaign. She is said to have accompanied her troops both on horseback and by foot.

Temple of Bel, Ruins of Palmyra, Syria. Photograph by James Gordon, Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Zenobia, The Conqueror

Zenobia’s reign saw a momentous military expansion program that significantly extended the boundaries of the Palmyrene empire through the neighboring regions. However, the motives for Zenobia’s military expansion cannot be confirmed. It is theorized that unlike her late husband, Odaenathus, Zenobia was unsatisfied with ruling a client state under Roman supremacy, so she took advantage of the Crisis of the Third Century in Rome that had resulted in instability in the allied states. It is also likely that the power vacuum in Rome during this period had caused economic uncertainty in the region resulting in the disruption of trade that may also have incentivized the Palmyrene incursion.

The Palmyrene military conquest was tolerated by two successive Roman emperors of the 3rd century, Gallienus and Claudius, and Zenobia took control of parts of Turkey, Arabia, Jordan, etc. It was the occupation of Egypt however, that became a turning point in Zenobia’s fortune.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Queen Zenobia Addressing Her Soldiers, ca. 1725 to 1730, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA. Museum’s website.

The Conquest of Egypt

The Palmyrene army invaded Egypt in 270 AD led by general Zabdas and aided by an Egyptian general named Timagenes. The invasion came at a time when the prefect of Egypt, Tenagino Probus, was preoccupied with naval expeditions against pirates. After an extended struggle for control, the Palmyrene army successfully annexed Egypt and declared Zenobia its queen.

This conquest of Egypt however, coincided with the ascension of Aurelian to the Roman throne. While her other conquests had been tolerated by the preoccupied Romans, Aurelian could not disregard the challenge to his newly obtained authority, particularly so as Egypt was a source of invaluable grain shipments for Rome.

The Capture of Zenobia (Tapestry from the Netherlands), ca. 17th century. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The Sacking of Palmyra

In 272 CE, Aurelian’s army first recaptured Anatolia and Egypt, causing the Palmyrenes to retreat to Syria. Zenobia retreated to Palmyra, which was besieged and where she was captured with her son. Her short-lived reign of six years collapsed in a single Roman campaign. Aurelian executed all of Zenobia’s supporters. However, he spared the lives of Zenobia and Vaballathus, bringing them to Rome and parading his triumph. Hosmer’s marble creation depicts Zenobia in a majestic form as she is paraded through the streets of the Imperial City by her captor’s army.

Sir William Boxall, Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, ca. 1857, National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC, USA. Museum’s website.

Harriet Hosmer, The Sculptor

Many centuries after Zenobia’s time lived an exceptional American woman named Harriet Goodhue Hosmer who redefined the notions of nineteenth-century femininity. After losing her mother and siblings at an early age, Hosmer was raised by her father, Hiram Hosmer, a wealthy physician who encouraged Hosmer in pursuits that were atypical for women during this period. Her father supported her pursuits of rowing, horseback riding, and skating; he taught her anatomy and even facilitated formal instruction; he encouraged her artistic pursuits leading to her ultimate interest and talent for sculpture at a time when women were not permitted to study live models.

Hosmer knew at the age of 19 that she wanted to be a sculptor, and came to an early realization that she would have to leave the United States in order to obtain training and hone her artistic skills. Much like Zenobia, Hosmer was perhaps discontent with the status quo and felt stifled by the limitations imposed on women in the nineteenth century.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Zenobia in Chains, ca. 1859, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, USA. Photograph by Maya Tola, Detail.

Hosmer’s Artistic Training

In November 1852, Hosmer traveled to Italy and entered the studio of the Welsh sculptor, John Gibson in Rome. Here, she first rendered studies from live models. Gibson was impressed by the young Hosmer and remarked on her uncommon talent.

Hosmer lived and worked in Rome from 1852 until the 1880s, thriving in a community of creative expatriates. These years found Hosmer developing her polished neoclassical style that was undoubtedly inspired by the grand statuary surrounding her in Rome and throughout Italy. She enjoyed considerable commercial success and lived a comfortable life with her income.

Although she received many notable commissions, she created Zenobia in Chains on her own accord, and it has been considered her most important work. Hosmer wrote that she picked Zenobia for “her womanly modesty, her manly courage, and her intellectual tastes.”

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra (Bust), after 1859, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Museum’s website.

Hosmer’s Zenobia

For two years, Hosmer studied Zenobia through literature, coinage, and libraries to conjure attributes and poses for the fabled queen. In the fall of 1857, Hosmer claimed “her whole soul was filled with Zenobia.” In her sculpture, she depicts the moment of Zenobia’s capture by Aurelian when she was marched through the streets in chains.

Hosmer’s depiction takes into consideration but deviates from canonical descriptions of the queen in Augustan history. In contrast to typical mid-19th century classical sculptures of captive women portrayed naked and in shackles, Hosmer’s Zenobia is dignified, fully dressed rather than a defeated feeble victim.

In this statute, Zenobia embodies an active pose, clutching her chains with her left hand hinting at defiance. Particularly when viewed from all sides there is a fluidity in her pose that conveys a dignified stride. Her stature is regal and her gaze is steady albeit lowered. Further demonstrating Zenobia’s contempt is the medallion with the head of Medusa on her belt.

The statute stands at 8 feet tall, laying emphasis on her majesty. The original and four known copies were rendered and small variations exist in the various versions, particularly in the articulation of the belt buckle.

Hosmer’s preference for female subjects is a reflection of her concern for the secondary status of women in the nineteenth century and Zenobia in the Chains is the absolute zenith of her extraordinary career.

When Zenobia in Chains debuted at the Great London Exposition of 1862, male critics wrote that a woman could not have had the skill or strength to execute such a monumental work.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Zenobia in Chains, ca. 1859, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, USA. Photograph by Maya Tola.

Mysterious End of Zenobia

There are many theories about how the tale of Zenobia concluded, however, historical accounts from this period were not particularly reliable and tend to significantly relied on conjecture or propaganda. Some many others claim she was spared along with her son to be displayed in the triumph of Aurelius in Rome, others theorize that Zenobia was beheaded along with her supporters during the conquest of Rome.

However, there are theories that suggest that Aurelian was so impressed with Zenobia’s strength through adversity that he freed her and granted her a villa in Tivoli. Some records indicate that her descendants assimilated into Roman nobility and were traced in the later 4th and 5th centuries.

Legacy of Two Exceptional Women

Zenobia’s short reign of a mere six years left its mark on history as a formidable challenger to the mighty Imperial Roman. She was, however, never forgotten and is deemed a Syrian hero. Hosmer achieved acclaim with her celebrated portrayal of Zenobia, establishing her reputation as one of the finest sculptors of the nineteenth century, and the first American woman to achieve international distinction as a sculptor. Her statuary is displayed at venues of distinction on both sides of the Atlantic.

James Wallace Black, Albumen silver print of Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, ca. 1860, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA. Museum’s website.