Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

10 November 2024 min Read

J. M, W, Turner’s Rain, Steam, and Speed is a masterpiece of Victorian Romanticism infused with hopes, fears, and reminisces. It catapults the viewer into the path of an oncoming train. Modernity cannot be avoided.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK.

Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 to begin a 63-year-long reign known as the Victorian era. It was an era marked by intense technological change and industrialization. One of the great symbols of the industrialized Victorian era was the rising presence of trains in everyday British lives. The first passenger trains were developed in the 1830s. By 1844, inexpensive one-penny commutes became possible under the Railway Regulation Act. This price regulation promoted a market boom to use more than 3200 kilometers of railway tracks circuiting the British cities and countryside. Within a short 15 years, the British public had adopted trains as a preferred means of transportation. Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) captures this exciting revolutionary method of travel through his painting Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway. It is a masterpiece of Victorian Romanticism infused with hopes, fears, and reminisces.

J. M. W. Turner, Self Portrait, ca 1799, Tate Britain, London, UK.

Turner painted Rain, Steam, and Speed in 1844, the same year as the Railway Regulation Act. It is an oil on canvas measuring 121.8 cm wide by 91 cm tall. Its 4:3 proportions showcase a bridge with a train on the far right, a smaller footbridge on the far left, and a rowboat in the mid-left. Several forms of reliable man-made transportation contrast against unpredictable natural weather.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

The canvas depicts, on the far right, Maidenhead Railway Bridge. It is presented to the viewer at a sharp oblique angle implying a great long distance. Maidenhead Railway Bridge spans the River Thames between the cities of Maidenhead and Taplow. It was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and constructed in 1839. It was notoriously famous because of its fear-inspiring design of only two brick arches spanning the wide Thames.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Hurtling toward the viewer is a great black train atop the Maidenhead Railway Bridge. It is a Firefly-class of locomotive which was celebrated for its top speed of 95 KPH despite its average commute speed of 53 KPH. However, even at 53 KPH, the Firefly was faster than a carriage ride of the early 19th century. Also, it had the added advantage of not needing a change of horses for long-distance travels.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

What is interesting is how Turner exposes the train’s internal fire to the viewer. It is almost as if Turner has removed the front shield of the train head to showcase the fiery coal burners. This machine is not just a shell of cold metal but an almost living being with an energetic core. It rushes towards the viewer with three puffs of steam trailing from its stack.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Behind the blazing engine are the passenger cars. Turner has depicted a 3rd class train carriage easily identified by its roofless construction. Most of the passengers wear hats, such as tophats and bonnets, to protect them from the typically British rainy windy weather. It would have been a terrible experience for a fashion-conscious passenger with hair being whipped about, the rain lashing at the clothing, and any face powders or hair pomades dissolving and dripping. While Turner’s passengers might arrive at their destinations on time, they must look like a frightful mess once they do arrive. As easily imagined, roofless carriages did not last long and soon fell out of use.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Turner’s train is heading West as the viewer is looking East towards London. Therefore, with its 3rd class passengers, it is safe to assume the painting depicts the after-work commute home. These passengers are not only rain-drenched but also mentally and physically fatigued after a long day at work. What is worse is that during the early Victorian era, a worker’s shift could easily be 10-12 hours long. Ouch! Imagine working 12 hours and then being wet the entire ride home. Terrible!

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Turner was a passionate admirer of Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665). These Old Masters encapsulated human elegance and natural beauty through their Neoclassical landscapes populated by divine figures and historical heroes. Turner, however, brushes aside the harmonious relationship between man and nature so loved by Lorrain and Poussin. Turner instead explores man versus nature. Technology fights and conquers nature’s life and limitations. A solid train against an ephemeral background. Humans travel at faster speeds than human feet can naturally provide.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Expanding upon this human-nature dynamic is a hare now barely visible in front of the train running towards the viewer. It is running for its life. Perhaps the hare wandered onto the bridge and now regrets its decision? Remarkably, hares can run at a top speed of 95 KPH matching the Firefly train’s top speed. Therefore, assuming this train is not at top speed, the hare has a potential chance of outrunning the train across the remaining bridge span and skirting to safety on the embankment. In this specific example, nature may win over man. However, this is a single battle as a man in the long term “wins” the war with ever-increasing technology and impact on the environment. The cornerstones of today’s ecological problems like climate change were laid in the optimistic and hopeful dawn of the Victorian era.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

To the far left of the canvas is a footbridge dating from the 1770s. It is depicted as vacant and unused. Perhaps the passengers of the train once frequented this bridge in a carriage or on foot before the construction of the Maidenhead Railway Bridge? This forgotten bridge is a symbol of the previous century before the arrival of 19th-century trains. It echoes a nostalgia for a simpler and slower time.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

In the water to the right of the footbridge is a rowing boat. Two people occupy the boat as it crosses the great river. Again, the viewer sees a remnant of the past. Besides daytrippers escaping to the country for an afternoon of relaxation, who uses a rowboat as a form of modern transportation? Hardly anyone. It is archaic, slow, and tiring.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Further to the right of the boat is a cluster of people all dressed in white standing on the shoreline. Are they maidens representing a lost Neoclassical past? A potential nod to Turner’s artistic heroes, Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin? They could be trainspotters, in their cool summery white clothing, waving to the new passing train. In the 1830s and 1840s, it was a form of amusement to stand outside and wave at passengers on nearby trains. The amusement is still beheld even today by the occasional passenger on modern trains. Why does a wave between two rapidly passing strangers seem so comforting? Perhaps it is a brief emotional connection reaffirming our common humanity despite the rapidly changing environment?

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

To the far distance right on the edge of the canvas, is a man plowing a field with two horses. Like the footbridge and rowboat, this tiny plowman is a flicker of a quickly disappearing era. The pre-industrial age is closing. Farms are becoming mechanized. Factories are replacing agricultural jobs. Homes are filled with manufactured goods. Turner’s painting explores the shifting balance between the agricultural world and the industrial world.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

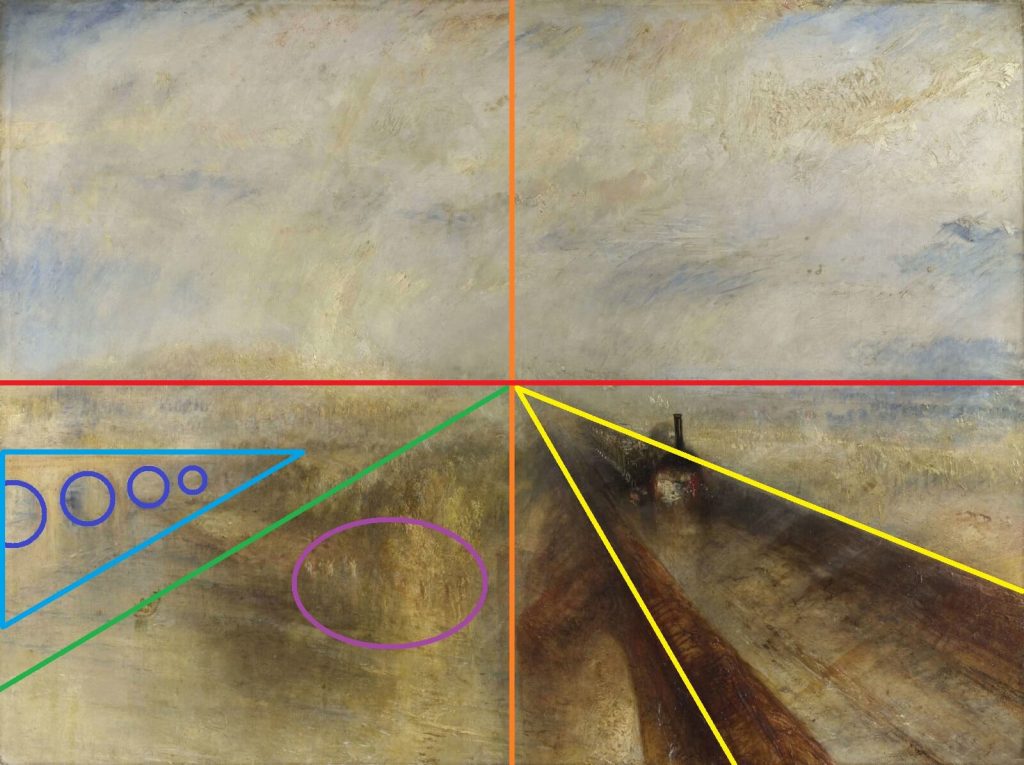

Despite its unrestrained composition, there is a hidden rigid geometry in Rain, Steam and Speed. It frames and delineates points of interest. It is entirely based on proportions and rhythmically sympathetic shapes. For starters the horizon line is along a central horizontal line, highlighted in red, equally dividing the upper and lower canvas. An orange line highlights a central axis that divides the peaceful left from the boisterous right. Then, on the right side is the Maidenhead Railway Bridge radiating from the painting’s center like sunbeams leaving the sun’s core. These yellow highlights complement the green line radiating in the bottom left sector. The green line crosses the rowboat in the water and makes a dynamic sweep across the grassy riverside. The footbridge, highlighted in turquoise, forms a triangle with a horizontal side parallel to the horizon, and its hypotenuse is parallel to the rowboat’s green line. Turner has created a moving dynamic without explicitly using diagonal lines. Further adding movement is the repetition of round spaces. Four consecutive circles, highlighted in indigo, form the footbridge’s arches. Their diameters shrink at a controlled pattern of 5, 4, 3 and 2 to create not only a regular rhythm but also a sense of receding distance. The round patterning is echoed in the oval group of trainspotters on the riverside, highlighted in violet. It has a ratio of 3:2 echoing the proportions of the footbridge’s last two circles.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Therefore, the red and orange bisecting lines add stability to the composition. The yellow, green and turquoise lines add radiating movement. The indigo and violet shapes add circular movement and moments of pause. Collectively, everything plays with each other to create order and interest.

Turner was a great painter during the era of Romanticism. This was an age of capturing energy and passion. Turner does not focus on the objective realism of the subject but rather on its subjective experience. Turner embraces the majesty of Lorrain and Poussin but not their clarity. Turbulent winds swirl with frothy pigment creating hazy forms and blurry outlines. Rarely has a composition been found in pre-Impressionist paintings with such an indistinct composition. Turner has dispensed with visual rationality and embraced visual emotionality.

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

When Turner painted Rain, Steam and Speed, he was 69 years old. He lived the first 25 years of his life in the 18th century and the remainder in the 19th century. During his lifetime, Britain changed into an almost unrecognizable new world. It was fast, furious, and somewhat frightening. Did Turner embrace this modernity with an open heart, or did he view it with skepticism and doubt? Was he hopeful or wistful?

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed, 1844, National Gallery, London, UK.

10,000 Years of Art. London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited, 2009.

Bradstreet, Christina. Talks for All: Turner’s Rain, Steam, and Speed. YouTube. National Gallery, London, UK, 30 May 2019.

Charles, Victoria, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, and Donald Wigal. 1000 Paintings of Genius. New York, NY, USA: Barnes & Noble Books, 2006.

Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

“Rain, Steam and Speed.” Collection. National Gallery, London, UK. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

“Self Portrait.” Collection. Tate Britain, London, UK. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!