Laura Knight in 5 Paintings: Capturing the Quotidian

An official war artist and the first woman to be made a dame of the British Empire, Laura Knight reached the top of her profession with her...

Natalia Iacobelli 2 January 2025

27 January 2023 min Read

Rebecca Solomon was a Jewish woman who overcame contemporary prejudices to become a successful artist in mid-Victorian London. In 2022, Princeton University Art Museum paid over $300,000 for her painting The Young Teacher (1861), representing a young white girl reading a book to her Black maid. The work is characteristic of Solomon’s interest in social issues and marginalized groups.

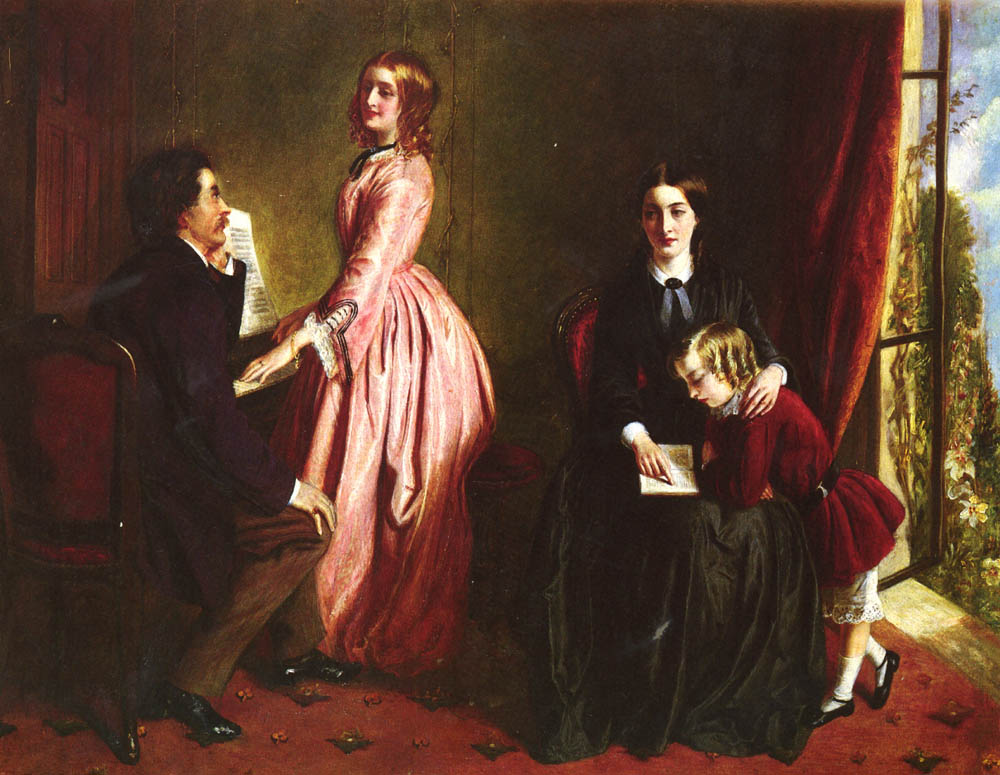

Rebecca Solomon, The Young Teacher, 1861, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Rebecca Solomon (1832-1886) was born into a liberal Jewish family in London. She was one of eight children, three of whom became successful artists. All of them were encouraged by their mother who herself was an amateur miniature painter. Rebecca’s brothers, Abraham (1823-1862) and Simeon (1840-1905), both studied at the Royal Academy. Abraham became a popular painter of Victorian narrative genre scenes, such as Second Class – The Parting (1855). Whereas Simeon became part of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, producing richly colored, sensuous images like Bacchus (1865).

As a woman, Rebecca was barred from studying at the Royal Academy and instead enrolled at the less prestigious Spitalfields School of Design. Subsequently, she was one of women who campaigned actively and successfully for the Academy to change its rules: the first female students were admitted in 1860. Rebecca lived and worked with Abraham at his London studio until his sudden death at the age of 39, and then lived with Simeon. When he was arrested and prosecuted for indecency in 1873, his disgrace sabotaged her own career. Although she still listed her profession as “artist painter” in the 1881 census, Rebecca never exhibited after 1874 and struggled financially. She died in poverty, after being run over by a hansom cab, amid rumors of alcoholism.

It is easy to dismiss Rebecca Solomon as a woman who succeeded because of her brothers’ fame, and whose work oscillates between their two distinctive styles. In reality, she was very much her own person. She had a wide circle of artistic friends, throwing parties which were described as “wildly incongruous” with the likes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne Jones, and literary figures like George du Maurier.

Despite being a single Jewish woman, she earned her own living working in John Everett Millais‘ studio as a painter of draperies. A determined and effective marketer of her work, she exhibited oils and watercolors throughout Britain. Solomon had a good commercial sense, cultivating a style which appealed both to buyers of narrative painting and those who were attracted to the decorative qualities of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Rebecca Solomon, Peg Woffington’s Visit to Triplet, 1860, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Rebecca Solomon’s subjects were also chosen with the buying public in mind. She often exhibited works based on popular literature or hot topics of the day. Peg Woffington’s Visit to Triplet, which was described as “a picture of great power” at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1860, illustrated a scene from a hit play of the time, Masks and Faces.

Five years earlier she painted The Story of Balaclava Wherein He Spoke of the Most Disastrous Chances in which a wounded officer is shown comforted by his bride-to-be. At the time, the British army’s poor performance in the Crimean War was a topic of national concern.

Rebecca Solomon, The Story of Balaclava Wherein He Spoke of the Most Disastrous Chances, 1855, private collection. Bridgeman Images.

Rebecca Solomon, The Lion and the Mouse: ‘Sweet Mercy is Nobility’s True Badge’, 1865, Museum of the Home, London, UK.

However, much of Solomon’s work, such as The Young Teacher, dealt with social inequality, and the prejudices which Solomon herself experienced as a Jewish woman. The Lion and the Mouse: ‘Sweet Mercy is Nobility’s True Badge’ (1865) presents the crime of poaching as a complex social issue that requires empathy, instead of harsh judgment.

Rebecca Solomon, The Governess, c. 1851, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The Governess (1854) brutally juxtaposes the hopeless plight of an impoverished single woman destined to never have either love or children of her own, with the happy couple absorbed in their music on the right. And A Friend in Need (1859), now only known from an engraving, compares the uncaring attitude of the male official with feminine sympathy towards a homeless mother and child. Solomon was an active campaigner for social causes: she volunteered at a soup kitchen and gave regularly to charity. And all of that is reflected in her work.

Rebecca Solomon, A Friend in Need, 1859, engraving after a painting, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

She also never forgot the prejudice she suffered because of her gender. Even in less narrative paintings, like the watercolor The Wounded Dove (1866), Solomon empathetically suggests the claustrophobic and trapped existence which was the norm for a middle class Victorian woman. Here, the female figure, squashed into the shallow space, swathed in over fussy fabrics, is as much an object of display as the ornaments on the mantlepiece. And the dove she holds becomes a metaphor for her own fate.

Rebecca Solomon The Wounded Dove, 1866, University of Aberystwyth, Wales, UK.

Rebecca Solomon succeeded in many ways in breaking free of the restrictions and expectations that 19th-century society imposed on her, but ultimately, and tragically, she too was wounded by them. Like many women artists, her work was forgotten after her death and much of it is now lost. What remains deserves to be better known.

Dr Carolyn Conroy and Dr Roberto C. Ferrari, Simeon Solomon Research Archive. Accessed 7 Nov 2022.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!