5 Facts about the Counter-Reformation in Art You Need to Know

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation spreading through Europe during the Renaissance.

Anna Ingram 5 December 2024

Renowned for its artistic flourishing, Renaissance Florence saw prominent families investing their fortunes into the city’s artistic enrichment. Consider the famous Medici and their contribution to buildings, palaces, and churches. They are but one among the many patrons of art and culture who strived to trade their wealth, power, and social standing for a lasting imprint of their legacy.

It is no secret among the Florentine families that their wealth came from family businesses. These inherited professions, from commerce to banking, often defied Christian values and cast a constant fear of being condemned in the afterlife. Thus, the more affluent commissioned the construction and decorations of chapels, hoping their sponsorship could translate into acts of repentance and pathways to salvation.

One example of such is the Brancacci Chapel, situated in the Carmelite Church of Santa Maria del Carmine. The patron of the chapel’s decoration was Felice Brancacci, heir of Florentine silk merchant Piero Brancacci. The fresco cycle was painted by Masolino and Masaccio and later finished by Filippino Lippi.

The interior design of the Brancacci Chapel conventionally displays frescoes narrating the life of Saint Peter, Piero’s patron saint. However, there is an exception in the upper left part of the chapel. Titled Tribute Money, this piece referring to the Gospel of Saint Matthew has a significance particularly profound in Florentine culture. Here, the tribute as a motif transcends monetary value to represent the symbolic cost of sins. It also goes to great lengths to capture its patron’s experience of expulsion, liberation, loss, banishment, redemption, and recovery.

Masaccio, Tribute Money, c. 1425, fresco, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, Italy.

Tribute Money betrays Felice Brancacci’s real motive behind his patronage. It had to do with his own business travels and trade negotiations and possibly was relevant to how he sold several family properties to finish the frescoes sooner. But overall, the chapel’s decorations reflect his desire for redemption. He believed such an act would save the Brancacci family from sin for generations to come, and ultimately cleanse their tainted merchant souls.

Another example of prominent Florentine families seeking redemption through the patronage of ancestral chapels was the Sassettis. In 1478, Francesco Sassetti acquired a chapel in the church of Santa Trinita. An influential personality within the Medici banks with direct control over their operations in Avignon, Geneva, and Lyon, Sassetti was an advisor to Piero de’ Medici and Lorenzo the Magnificent as well as his financial assistant. He eventually rose to the General Manager of the Medici Bank, further solidifying his authority and prominence within the Medici family’s extensive banking network.

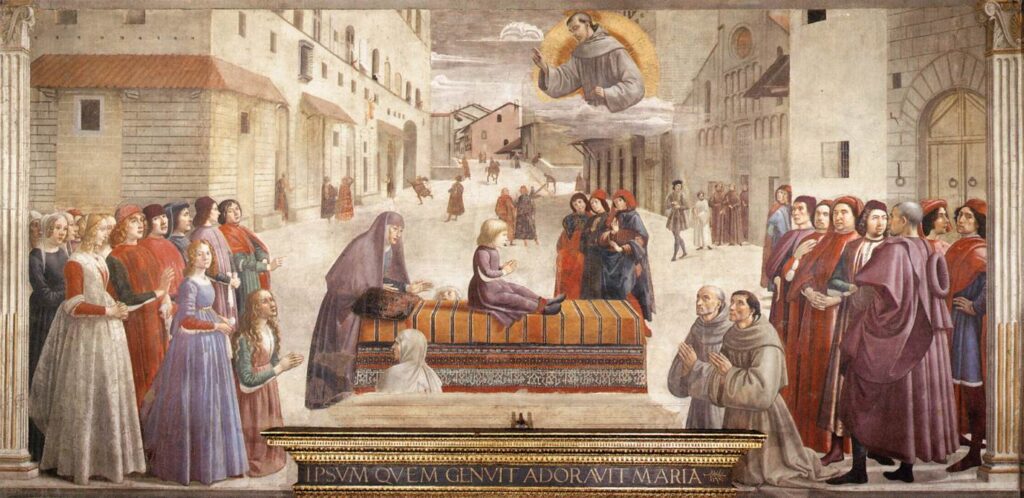

Domenico Ghirlandaio completed the chapel decoration, depicting scenes from the life of Saint Francis, patron saint of Sassetti. The result has a specific arrangement of the fresco scenes revealing the purpose of the chapel. That said, the fresco, The Resurrection of the Notary’s Son, takes the central position on the main chapel wall, just above the altarpiece. This scene is a commemoration of Sassetti’s firstborn child, who passed away during infancy. As its theme suggests, it shows the family’s unwavering belief in the child’s resurrection and eternal life. Additionally, the placement of Sassetti’s tombs inside the chapel extends that wish to other family members, forming a collective aspiration for redemption and salvation of the soul.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Resurrection of the Notary’s Son, 1479-1485, fresco, Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinita, Florence, Italy.

Another scene, Francis Renouncing His Worldly Goods, addresses the same theme even more directly. Interestingly, the setting is not Assisi, the hometown of the Saint, but in Geneva, a prominent banking center where Francesco Sassetti amassed much of his wealth. It is also important to note that canon law considered money-lending business a sin. Patrons, who preoccupied themselves with banking-related endeavors, such as Sassetti, sought various strategies to facilitate a more direct route to heaven. Reenacting the scene about St. Francis’ rejection of worldly wealth and his commitment to a life of humility and spiritual dedication, specifically in the city where Sassetti handled money for life, expresses the patron’s departure from materialism and thus foregrounds his repentance.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Renunciation of the Worldly Goods, 1479-1485, fresco, Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinita, Florence, Italy.

The Brancaccis and the Sassettis demonstrate how wealthy Florentine families were conscious of the nature of their businesses. Thus, they invested in family chapels, choosing specific themes to repent and aspire for eternal salvation.

Maria DePrano: “Introduction”, in Art Patronage, Family, and Gender in Renaissance Florence: the Tornabuoni, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 1-9.

Nicholas A. Eckstein: “The Widows’ Might: Women’s Identity and Devotion in the Brancacci Chapel”, Oxford Art Journal 28, 2005, 1, p. 99–118.

E.H. Gombrich: “The Sassetti Chapel Revisited: Santa Trinita and Lorenzo de’ Medici”, I Tatti Studies, 1997, 7, p. 11–35.

Debra Louise Hintz, “The legend of St. Francis in the Bardi Chapel and in the Sassetti Chapel”, The University of Arizona, 1983, p. 60-104.

Dale Kent: “The Brancacci Chapel Viewed in the Context of Florence’s Culture of Artistic Patronage”, Florence, Villa I Tatti, June 6, 2003, Ed. by Nicholas A. Eckstein, Florence, 2007, p. 53-71.

Aby Warburg: “Francesco Sassetti’s Last Injunctions to His Sons”, in The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1999, p. 223–62.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!