The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

On International Migrants Day, we remember the persecution of artists by oppressive and authoritarian regimes. Artists who fled the Nazi regime in World War II are perhaps the most known artists forced into exile. Many escaped to England and to America. But what many people do not know is that a small network of refugee artists from both World Wars chose Wales as their home.

Croeso! Welcome, as we say in Wales.

Wales is a small country, part of the UK, but very different in terms of landscape, national identity, language, and culture. Cymru, to give Wales its true name, is bordered by England on one side, but by open sea to the West, North, and South. Wales, used to years of oppression from the English, perhaps has an enhanced sympathy for the lost and the dispossessed. Cymru has opened her arms and witnessed an influx of refugee artists, many of whom are now firmly entrenched in the Welsh cultural landscape.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Heinz Koppel, Merthyr Blues, 1955, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, UK.

Two famous Welsh sisters, Gwendoline and Margaret Davies, were wealthy art patrons who put together one of the greatest British art collections of the 20th century. They opened their home to Belgian artists fleeing persecution in the First World War. This was not just altruistic, but to positively encourage a cross-fertilisation of talent, and to contribute to the cultural heritage of Wales. Perhaps their most famous visitors were the De Saedeleer family, whose impact was felt across Welsh culture. They influenced how art was taught at the University of Aberystwyth and were involved in the development of an artists’ colony at the Davies sisters’ stately home, Gregynog Hall.

Gregynog Hall, home of the Davies Sisters, Newtown, Wales, UK. Gregynog.org.

The work of landscape painter Valerius de Saedeleer (1867–1941) was informed by Symbolism but built on his immersion in traditional Flemish landscape painting. In Aberystwyth, he discovered inspiring new landscapes. In Wales, he painted not just the external beauty of nature, but also explored the soul of the place.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Valerius de Saedeleer, Winter Landscape near Aberystwyth, 1914-1920, Gregynog Hall, Newtown, Wales, UK.

George Minne’s (1866–1941) work in Wales is reminiscent of Käthe Kollwitz – the mother mourning for her child, and the uncertainty and instability of loss. Minne grounds himself in biblical themes, mostly in black and white charcoal images, with figures in deep spiritual conflict. The horror of war is ever present, as in the sculpture of a grieving mother, below.

Refugee Artists in Wales: George Minne, Grieving Mother Protecting Her Children, 1888, Museum Bojimans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Photographer Edith Tudor Hart (1908–1973), originally from Vienna, fled Austria in 1933 with her husband Alex Tudor Hart. While Alex worked as a doctor in the Rhondda Valley in South Wales, Edith photographed miners and other aspects of daily life in Wales as the 1930s Depression hit. The image below shows the demonstration against government cuts to unemployment benefits.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Edith Tudor Hart, Unemployed Workers Demonstration, Trealaw, South Wales, 1935, National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, Wales, UK.

In the hands of the person who uses it with feeling and imagination, the camera becomes very much more than a means of earning a living. It becomes a vital factor in recording and influencing the life of people and in promoting human understanding.

Refugees From National Socialism in Wales project website.

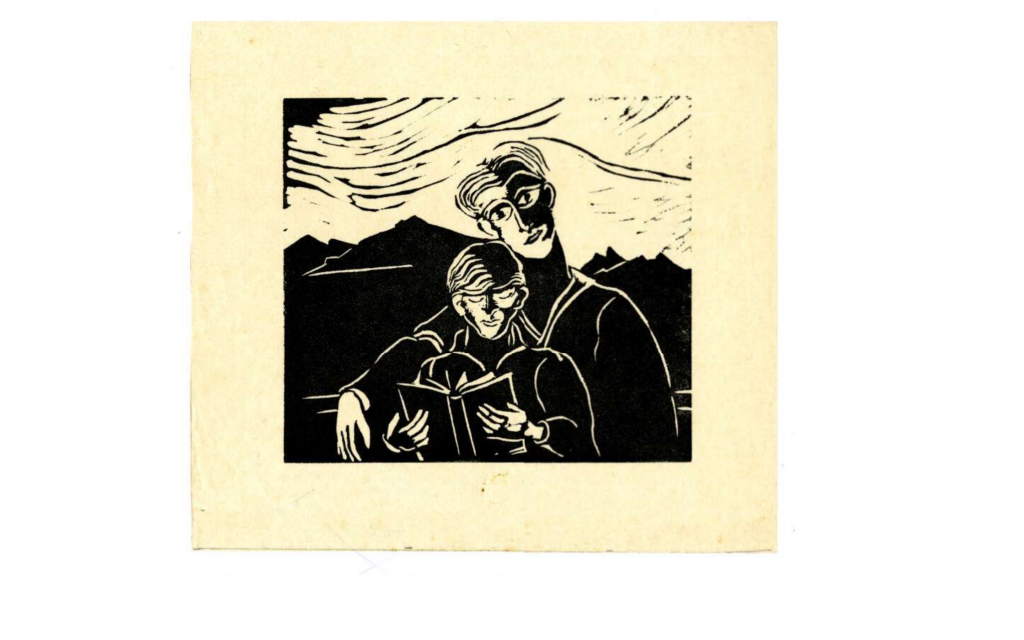

The sculptor and printer Bettina Gross (later Bettina Adler) began carving in wood at a very young age. She emigrated to Wales in 1939 to join a Jewish émigré community. She worked at a button factory in Merthyr Tydfil, but continued with her art, concentrating on linocuts and fabric designs. She married the poet and historian H. G. Adler, and their son Jeremy Adler is a well-known British scholar and poet. Both are shown in the touching woodcut below.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Bettina Adler, Father and Son, one of a series of woodcuts, 1939-1947, British Museum, London, UK.

Some artists came to Wales, found a new community, and adopted a new homeland. Josef Herman, discussed below, is a prime example. Some, however, found just melancholy and isolation, and quickly returned home if and when they could. Some, like Gustave Van de Woestyne (1881–1947) and Emile Claus (1849–1924), simply couldn’t settle in Wales, and moved quickly to London. Others were overwhelmed by their loss, and simply gave up their art, or even their lives. The Welsh word hiraeth describes an unfathomable longing for a home that may not even exist. Hiraeth can break your heart.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Emile Claus, Sunset over the Thames, 1916, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium.

Josef Herman (1911-2000) was a Realist artist, known for his sketches and paintings of working people. He was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1911. In 1938, he fled from the Nazis to the UK. He lost his entire family in the Holocaust. In 1944, Herman came to Ystradgynlais, a mining town in the Swansea Valley, for a holiday. He ended up staying over a decade! Inspired by the strong sense of community in Ystradgynlais, he became an important part of the local community where he was fondly nicknamed “Joe Bach” (Little Joe).

Refugee Artists in Wales: Joseph Herman, Miners, Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton, UK.

Here was a homecoming in that sense of the word which is the domain of the soul…. Home for the imagination furthered by an environment to fertilise it to fruition. A place in which to grow and rest.

Nini Herman, “Josef Herman a Working Life,” 1996, Quartet, London, p. 85.

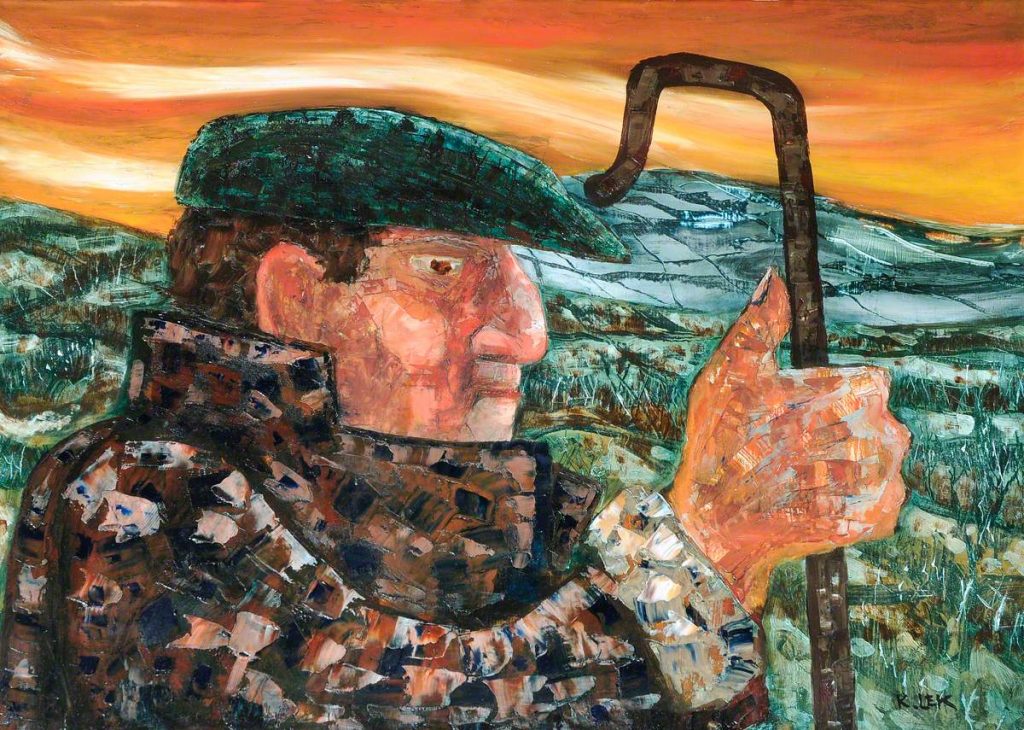

Artist, designer, and teacher, Karel Lek (1929–2020) was a Jewish refugee from Antwerp, Belgium. He arrived in North Wales as a boy in 1940, and spent the rest of his life there painting the local people and landscapes. He died aged 90 in 2020 in Bangor, North Wales. Perhaps fittingly, this adopted Welshman died on St David’s Day, the most important day in the Welsh calendar.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Karel Lek, Shepherd, Oriel Môn, Llangefni, Anglesey, Wales, UK.

I paint continuously and mostly my subjects are my fellow men and women in whatever situations I find them, whether in urban or rural surroundings. I am certainly not insensitive to the beauty of the landscape which surrounds me, but it’s the changing moods of the seasons of autumn and winter which appeal to me most.

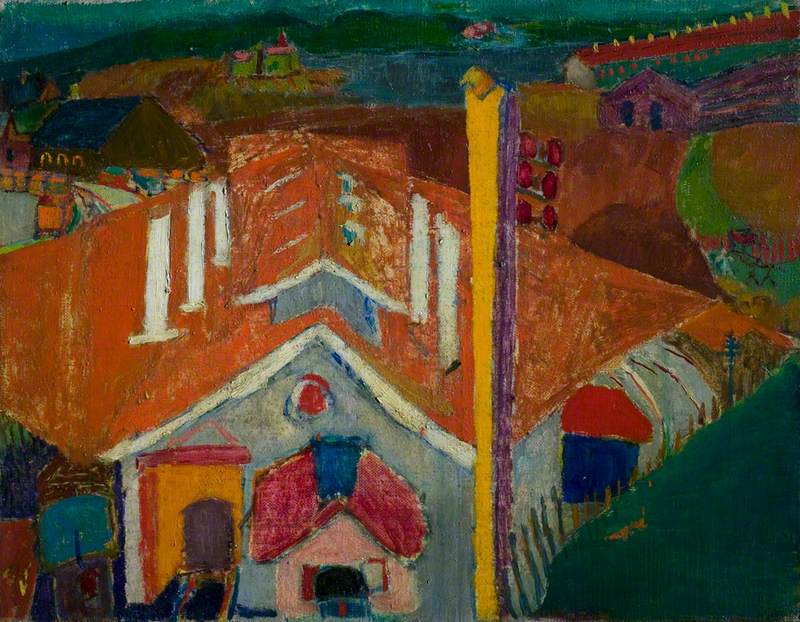

Born to Jewish parents in Berlin, Heinz Koppel (1919-1980) fled Germany in 1933 with his father. His mother stayed behind, disabled by arthritis, and was later murdered in the Treblinka extermination camp. Heinz Koppel’s work is influenced by Freudian psychoanalysis, German Expressionism, and Surrealism.

In 1944, he settled in Dowlais near Merthyr Tydfil, where he taught art to both children and adults. The natural landscape was an important subject in his paintings, but he was at the same time fascinated by the decaying industrial areas of Wales. He left Wales for a while, but returned in 1974, settling in Cwmerfyn near Aberystwyth. Koppel was a key figure in the “56 Group” promoting Welsh modernist art.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Heinz Koppel, The Engine Shed, Dowlais, 1951, Leicester Museums and Galleries, Leicester, UK.

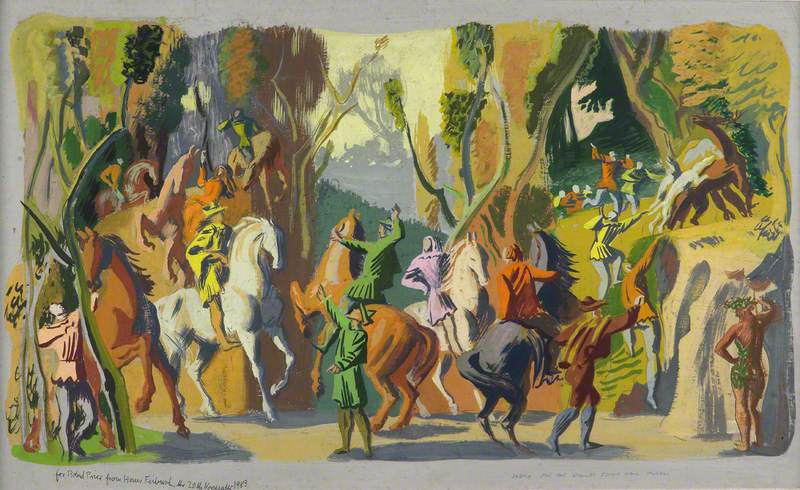

Although he didn’t actually settle in Wales, we are including German-Jewish Hans Feibusch (1898–1998) in our list as he contributed significantly to Welsh institutions. Best known for his colorful murals, Feibusch painted 12 huge works which adorn the central hall of Newport Civic Centre. Architectural expert John Newman describes them as “perhaps unsurpassed in twentieth century Britain.”1 And as if that is not enough, Feibusch also painted murals in the quaint and curious village of Portmeirion in Gwynedd.

Refugee Artists in Wales: Hans Feibusch, Sketch for Dudley Town Hall Mural, Dudley Museum and Art Gallery, Dudley, UK.

If we look back to our ancient roots, we are all travelers. Wherever you sit reading this today, your ancestors were migrants! So many countries have a past history of offering safe refuge to the persecuted, receiving a rich injection of creativity in return. We need to remember that history.

The Welsh Government voted against the United Kingdom Governments’ Nationality and Borders Bill. On his Twitter account, The First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, condemned it as a cruel and inhumane response to those seeking safety. In contrast, Wales plans to continue to be a “Nation of Sanctuary,” offering safe spaces to refugees.

View of Portmeirion, Wales, UK. Photo by Mike McBey via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

John Newman, The Buildings of Wales: Gwent/Monmouthshire, Penguin Books, 2000.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!