5 Facts about the Counter-Reformation in Art You Need to Know

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation spreading through Europe during the Renaissance.

Anna Ingram 5 December 2024

The most important function of portraits is to preserve the memory of the sitter. The desire for being remembered is a natural human trait that is expressed primarily in the arts. In antiquity, rulers would have their likenesses sculpted or pressed on coins. Similarly in the Renaissance, only royalty, the aristocracy, or well-to-do citizens could afford to have their portraits executed by top artists of the period. Here we present a selection of the seven most intriguing portraits from the 2021 Remember Me exhibition in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the first major show that brought an unprecedented number of international Renaissance portraits to one place.

Rijksmuseum’s frontal façade with the Remember Me exhibition poster, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Museum’s Facebook account.

Nowadays we all can take photographs of ourselves. The sitters, just like us, were keen to present themselves in the most favorable light possible. All aspects of our self-presentation – facial expression, lightning, pose, background, and clothing – are the result of meticulous planning, aren’t they? Where one person might focus on physical beauty, another would prioritize a level of education or a sense of authority.

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Petrus Christus, Portrait of a Young Girl, ca. 1470, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany.

The Northern Renaissance masterpiece Portrait of a Young Girl (c. 1470) by Petrus Christus is a highlight of the Gemäldegalerie collection, and this exhibition marked the first occasion the painting had left that museum since 1994.

In this elegant portrait we can see an anonymous young woman, dressed in the Burgundian style that was popular in both France and the Low Countries around 1470. This portrait combines the immaculate beauty and inaccessibility of enigmatic women worshipped by courtly poets. The porcelain-like mask of the anonymous model conveys the ideals of beauty at the Burgundian courts.

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait at the Easel, c. 1556-1557, Łańcut, Muzeum-Zamek w Łańcucie, Poland.

As we know, female painters were an extreme rarity in the early modern era, given the fact that they could not exercise any profession nor obtain any education. In this portrait a young woman, Sofonisba Anguissola, depicts herself as an artist at work. She came from a well situated family in Cremona with courtly ambitions but limited financial means. The reason why she became a renowned artist was that her father provided her with best private education in music, literature and painting.

Anguissola came to be a successful artist as she served at the Spanish court as a lady-in-waiting and gave painting lessons to Elisabeth of Valois, Philip II’s third wife. She produced portraits of various court members and also left behind numerous self-portraits that likely served as means of self-promotion, but also as a representation of her status and her level of education.

In this self-portrait she depicted herself working on a Virgin and Child theme which can be read twofold: she could be inspired by the legend of Saint Luke, who was believed to have painted the very first image of Virgin Mary; but also Anguissola emphasizes her status as an artist by choosing to display herself as a painter of religious and historical themes.

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Jan Jansz. Mostaert, Portrait of an African Man (Christophle le More?), ca. 1525-1530, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

This remarkable Portrait of an African Man by Jan Jansz. Mostaert comes directly from the Rijksmuseum’s own collection.

The small panel is known to be the very first painted portrait of an African in European art and by far the only one until the 17th century. The man is portrayed as a Christian, signified by a pilgrim’s badge of Our Lady of Halle on his bonnet, a popular pilgrimage shrine near Brussels. For many years art historians presumed that this lavishly dressed and elegantly portrayed African man was a nobleman from the imperial court of Charles V, but after a closer look at his attire we can see that his clothing cannot be associated with the imperial fashion. Further analysis of his costume revealed he was not wearing a paltrock, a skirt that gentlemen wore over their hose, which was an important element of the 16th-century court fashion.

This man’s identity remained a mystery for scholars until Dutch historian Ernst van den Boogaart suggested that the man could have been Christophle le More, a bodyguard of Emperor Charles V.1 Le More’s presence was well documented in records from that period. He was born presumably around 1490 in Spanish slavery and could have arrived in the Netherlands with the entourage of Joanna of Castile.

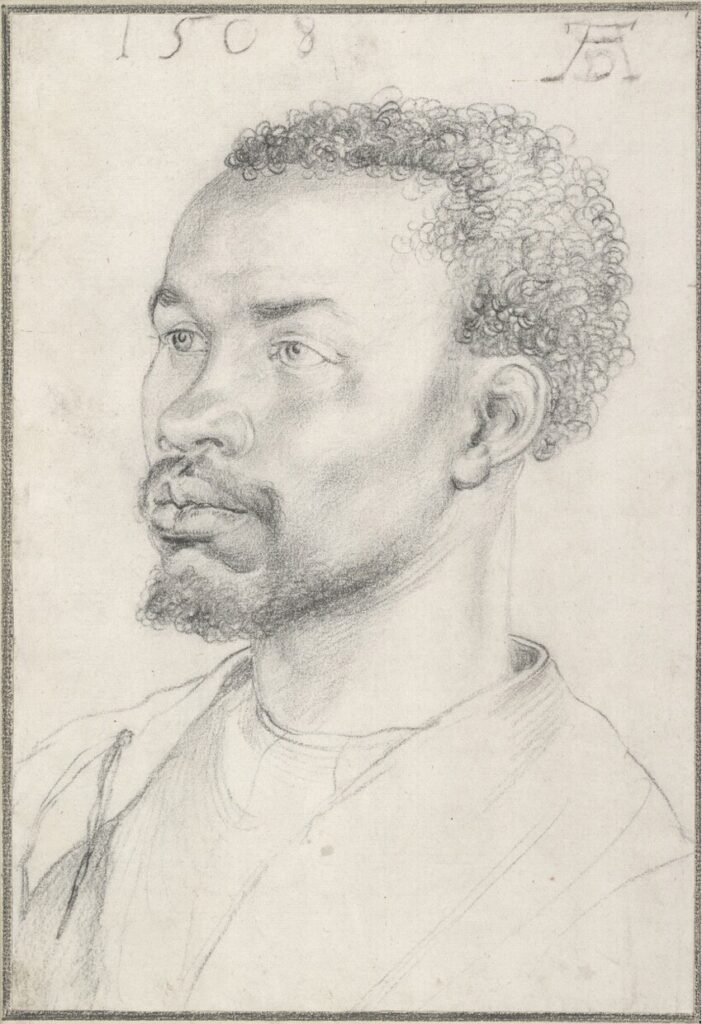

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of an African Man, 1508, Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

Albrecht Dürer, an excellent Nuremberg painter, engraver, draughtsman and art theorist, in his lifetime created around a thousand sheets of impressively lifelike portraits of his contemporaries. At the Remember Me exhibition you could see an example of such a remarkable drawing made by Dürer of an anonymous African man.

This is probably the earliest known drawing of a Black person in European art. As the inscription on the sheet suggests, the drawing was made in 1508, around 20 years before Mostaert’s painting. We, alas, do not know who the anonymous man was and how the artist encountered him. Dürer met numerous Africans during his travels to Antwerp or Venice from diaries and drawings (or sketches) he made. He portrayed a Black woman in a famous sketch known as Portrait of Katharina (1521), and employed a Black king and a Black servant in his rendering of The Adoration of the Magi (1504) which is the only known work featuring African figures in his paintings. Dürer was clearly fascinated by them, especially by their bodies which he described as:

(…) so well built and handsome that I have neither seen nor can imagine something better built.

Left: Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of Katharina, 1521, metalpoint on paper, Galleria degli Ufizzi, Florence, Italy; Right: Albrecht Dürer, The Adoration of the Magi, 1504, Galleria degli Ufizzi, Florence, Italy. Detail.

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of a Young Woman in Prayer with her Hair Down, 1497, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

This was an another work by Dürer brought to Amsterdam for the exhibit. The young woman captured praying by the Nuremberg artist is reminiscent of depictions of Mary Magdalene, whom we can see in religious scenes with loads of curls covering her body.

The first question that comes to the mind is: who is she? According to scholars this cannot be a religious representation of a saint, but rather an individual portrait. This young woman is depicted with a modest dress covering her décolleté, as worn in Nuremberg. Also the way she wears her hair down suggests that she is still in an adolescent. Since Dürer often depicted his family members, we could presume that this portrait is of one of his sisters, Anna or Agnes, who in 1497 were respectively 15 and 18.

Interestingly, this painting is believed to be a pendant (pair) of another portrait of a young woman painted in the same year. (Unfortunately the work shown below was not included in the exhibition, but it is nonetheless worth mentioning here!)

Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of a Young Woman with her Hair Done Up, 1497, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

The portrait of a lady with hair up has the exact same size (56.5 × 42.5 cm) as the portrait of the lady with hair down. Moreover, they were both painted in watercolor on fine canvas. Hence scholars suggest that these two portraits must have been meant as a pair.

The woman with her hair done up is representing the opposite values and attitude of the first, slightly introverted girl. She looks the spectator daringly in the eye, wearing an open dress meant for dancing and in her hand we can see Artemisia abrotanum (or lad’s love, southernwood) which is a flowering plant that was thought to have an aphrodisiac effect. We can thus presume that the sitter is of marriageable age.

It is suggested that this pair represents two portraits of the same woman in two stages of her life: before and after puberty.2

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Hans Memling, Portrait of Bernardo Bembo, c. 1471–1474, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium.

This exquisite portrait by Hans Memling came from the collection of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, which has been under a massive renovation project for many years and has just recently reopened.

The man depicted here is Bernardo Bembo, a Venetian humanist who commissioned his portrait from Bruges’ most desired portrait painter while he was an envoy at the court of Charles the Bold in Flanders from 1471 to 1474. Bembo’s facial expression is calm and sophisticated, gazing somewhere in the distance but showing an antique coin in his hand directed at the viewer. The coin depicts Emperor Nero, which stands for an attribute for the erudite collector.3 Although the portrait may at first seem to be Italian in style, the meticulous precision and distinctive vivid colors betray its Northern origin.

Other symbols discreetly revealing the sitter’s identity are two small laurel leaves painted just at the bottom of the panel and an olive tree that stands out in the landscape on the right. They both refer to Bembo’s personal emblem which consisted of a laurel spring and a palm frond.4

Renaissance Portraits in Rijksmuseum: Sofonisba Anguissola, The Chess Game, 1555, The Raczyński Foundation, National Museum, Poznań, Poland.

Last but not least, I present to you Sofonisba Anguissola’s beautiful family portrait The Chess Game from Polish collections. This painting attests to family ties and the importance of birth and descent in Renaissance Italy.5

Anguissola painted her three sisters, Lucia (?), Europa, and Minerva with their maidservant. The young ladies are placed around a chessboard and painted while playing chess. The game of chess was not chosen randomly as the subject of this painting. It emphasized not only the intimacy of the sisterly relation, but also their high status. Everything in this composition attests to their elevated position: chess, costly dresses with accessories, and an oriental carpet on the table.

By 1566, when Italian artist and writer Giorgio Vasari saw this painting in the family palazzo in Cremona, two of the sisters, Lucia and Minerva, were already dead meanwhile Sofonisba was working at the Spanish court.

E. van den Boogaart. “Christophle le More, Lijfwacht van Karel V?.” Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 53 (4) 2005. Pp. 412-433.

S. van Dijk, M. Ubl, with contributions by F. Lammertse, Remember Me, Rijksmuseum, exhibition catalogue. Amsterdam 2021, p. 29.

Remember Me…, 2021, p. 210.

Remember Me…, 2021, p. 210.

Remember Me…, 2021, p. 76.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!