5 Facts about the Counter-Reformation in Art You Need to Know

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation spreading through Europe during the Renaissance.

Anna Ingram 5 December 2024

20 September 2024 min Read

Renaissance tapestries are the most underestimated subject in art history. As expensive and enormously large works of art, tapestries attributed to the owner’s wealth and status more than anything else in Renaissance Europe. While only a few Renaissance tapestries remain intact today, their value and magnificence deserve a spotlight. Although they appear in the background of television shows such as The Serpent Queen and Becoming Elizabeth, most viewers might not know their historical significance or production. Yet, in their simplest forms, Renaissance tapestries are made of silks, wool, gold, and silver threads. Here’s everything to know about Renaissance tapestries.

The Falcon Hunt, ca. 1500–1530, woven in Southern Netherlands, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

First, the designer sketches a preliminary drawing for the composition of the tapestry, called a petit patron in French. Next, a painter copies the design and enlarges it to the intended size of the tapestry; this painting is called a cartoon. The cartoon is then given to a tapestry weaver. At this point, the weaver might implement some changes to the design, such as thread colors. When comparing a tapestry to its cartoon, its composition is in reverse due to the weaver’s technique of copying the cartoon by using a mirror.

Designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Saint Paul Directing the Burning of the Heathen Books, from a nine-piece set of the Life of Saint Paul, before 1539, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA. Photo by the author.

Like any other weaving practice, a tapestry is woven with a weft and warp process. A warp runs vertically, while the colored weft yarns are woven in a tabby binding pattern only where color is necessary. The weft yarns are finer than the warp yarns. This allows the weaver to tightly pack the yarn and create the ribbed effect of a tapestry.

Luckily, the weavers knew exactly where to place the expensive threads since they had the cartoon to refer to. The best early example is Pope Leo X’s Acts of the Apostles tapestries and their accompanying cartoons at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Woven in the workshop of Pieter van Aelst, designed by Raphael, Christ’s Charge to Peter, from the Acts of the Apostles, 1516-1517, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City. Detail.

Recently, the 500-year-old tapestry set was on display in the Sistine Chapel, where they were originally intended. However, their creation began in 1515 when Leo X commissioned Raphael to create a series of paintings (known as cartoons) that would serve as models for the Acts of the Apostles’ tapestries. As the first step in a tapestry’s production, a painted cartoon would be placed behind the warp and visible between threads. Remarkably the Acts of the Apostles’ cartoons still exist today, unheard of for other surviving tapestry sets.

Leo X’s tapestries were woven between 1516 and 1521 in Brussels at Pieter van Aelst’s workshop. The tapestries were designed for the Sistine Chapel’s lower walls and emulate Leo X’s life and Catholic beliefs. They are a perfect example of religious imagery in a tapestry set. But not all Renaissance tapestries were made for religious purposes.

Master MGP and Antoine Caron, Elephant from the Valois Tapestries, c. 1576, Uffizi Galleries, Florence, Italy. Detail.

For instance, the royal courts of Europe also commissioned magnificent tapestries for multiple uses. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the most powerful monarchies in Western Europe were England, France, and Spain. From 1477 until the 1520s, the countries secured alliances through political marriages. Tapestries were displayed at these royal weddings, signifying wealth, power, and, most importantly, the political affiliations bound by marriage. This is where Renaissance tapestries flourished and became more valuable than paintings.

Woven tapestries also provided a practical purpose. They were used as wall hangings in residences during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Their goal was to shield outside light and provide warmth to the home during the cold winters. Since these tapestries covered entire walls, their imagery became the perfect real estate for propaganda.

Design attributed to Pieter Coecke van Aelst, woven by Willem de Pannemaker, The Circumcision of Isaac and the Expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael from the Story of Abraham series, ca. 1540-1543, Hampton Court Palace, London, UK.

For example, Henry VIII proclaimed his authority as holy ruler of England through the commission of the Story of Abraham tapestries. This set hangs in situ (in their original location) in the Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace. The ten tapestries were probably designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst in 1537 and woven by Willem de Kempeneer’s workshop in Brussels between 1541 to 1543.

But why would someone like Henry VIII want a woven tapestry rather than a traditional painting? This is because the tapestry showed a high level of artistic skill that the owner could afford. While from afar, they looked like large compositional paintings, upon closer view, their interwoven threads of gold and silver shimmered in the light.

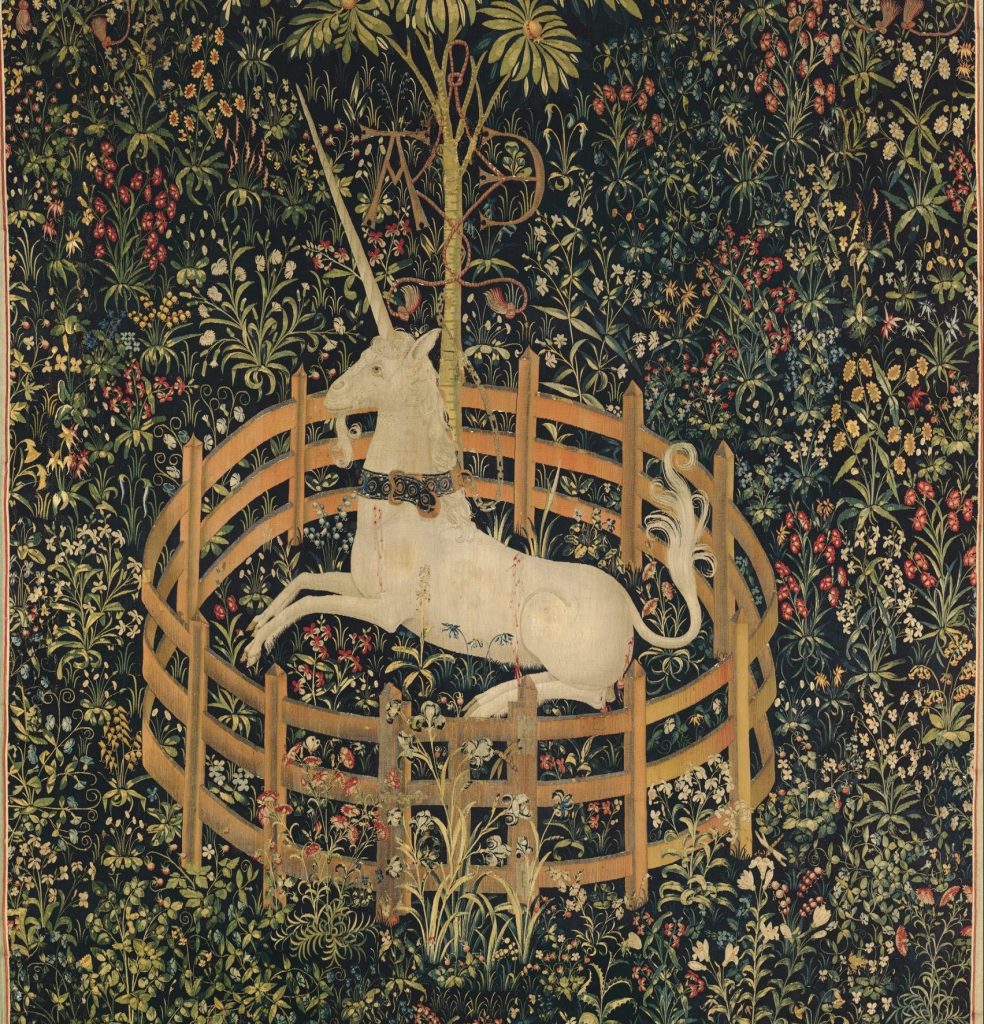

The Unicorn in Captivity, from The Unicorn Tapestries, 1495-1505, The Met Cloisters. New York, NY, USA.

While there can be some confusion in identifying a medieval or Renaissance tapestry, the best way to differentiate the two periods is through the composition of the tapestry. Typically, Medieval tapestries display multiple narratives in one compositional piece. On the other hand, Renaissance tapestries have various panels that each show a specific moment in time. In fact, Raphael’s cartoons for Leo X’s Acts of the Apostles introduced the new Renaissance style that revolutionized tapestry production during the 16th century.

Finally, since most of the Renaissance tapestries remaining today have “presumed” production dates, art historians cannot entirely claim a tapestry to be purely from one period or the other.

Hans Baron. “Fifteenth-Century Civilization and the Renaissance.” In The New Cambridge Modern History, edited by G. R. Potter, 50–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957.

Adolph S. Cavallo. The unicorn tapestries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

Elizabeth Cleland, ed. Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014.

Rosamund Garrett, and Matthew Reeves. Late Medieval and Renaissance Textiles. London: Sam Fogg, 2018.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!