Surrealist Meret Oppenheim in 5 Artworks

Exploring five works by female Surrealist Meret Oppenheim

Candy Bedworth 26 September 2024

You must have already encountered René Magritte’s series of paintings on lovers marked by his unmistakable surreal style and renowned wit. However, depicted was something more profound about love deep inside the paintings’ haunting beauty, which raises the question: What was Magritte’s message in these images? Will Lovers remain timeless outside the context of our contemporary reality?

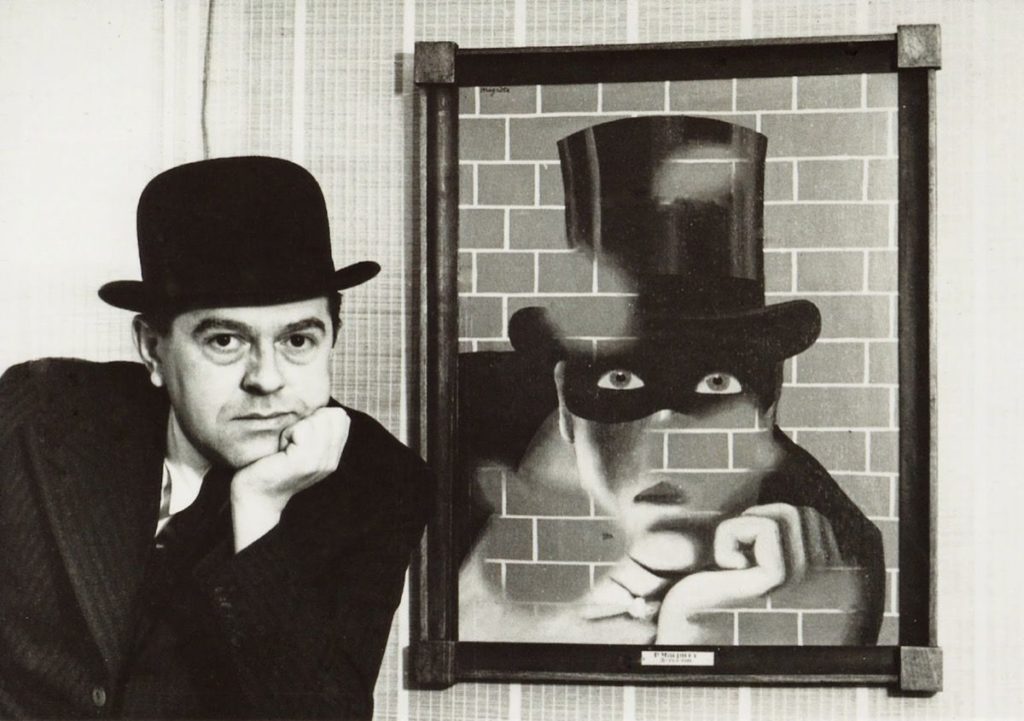

Magritte painted four variations of The Lovers in 1928. We recognize such a close-up of a kiss from the movies. But in the two most well-known versions of the paintings is one mysterious element—the faces shrouded in cloth.

The Surrealists were captivated by masks, disguises, and what lies beneath the surface. These particular melodramatic scenes may also relate to the graphic illustrations in pulp fiction and thriller stories. One of them Magritte became absorbed with was Fantômas, the shadowy villain of a series of thriller novels and, subsequently, films whose identity remained unrevealed with his face wrapped in cloth.

But there is another, much darker origin. When René Magritte was thirteen, his mother committed suicide, and her body was found in Sambre, supposedly with her nightgown around her face. As he said, he never found out “whether she had covered her eyes with it so as not to see the death she had chosen, or whether she had been veiled in that way by the swirling currents,” but it must have been a traumatic event.

Nevertheless, let’s move on to the paintings themselves.

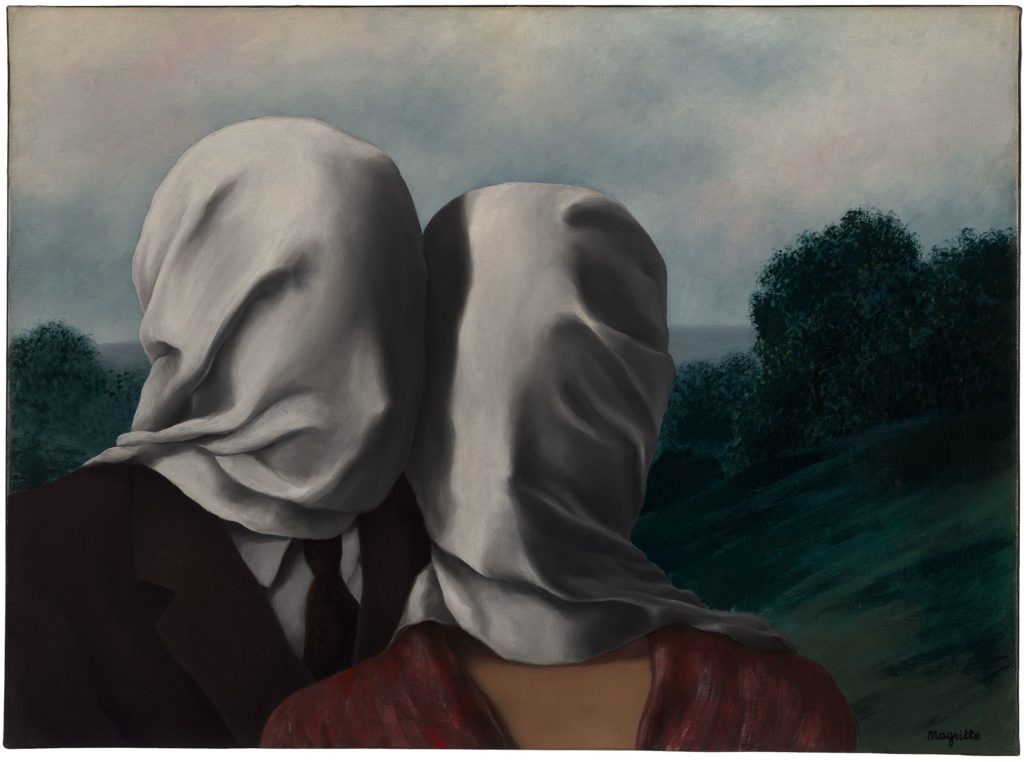

In The Lovers I, a man and a woman press their faces close together in an affectionate gesture, almost as if they were in a family portrait. It could be a breezy, Instagram-like holiday snapshot with a lovely forest and sea in the background. Only, there is a cloth that drapes on their faces, forming curls over their shoulders like ropes. Due to these elements, this moment of intimacy translates into a spectacle of alienation, suffocation, and even death. The lovers are unable to communicate or touch. The cloth keeps the two figures physically apart.

The second version of The Lovers is similarly composed but with a more disturbing tension—in this version, it comes to show as the man and woman, dressed as they were in the original, lean in for a loving embrace—a kiss. Their attempt is again muffled by the white fabric. Unlike the pastoral scene of the previous painting, here, a much more abstract background is present.

Here, we may have a window into the hidden aspects of relationships that even the participants themselves are blind to. When the two individuals in the pieces embrace or kiss, they cannot see the other in a literal sense, with both of their heads shrouded by a (presumably) opaque hood. We always have trouble reading between the lines, feelings, and secret fantasies of those we love. No matter how much you pose, how much you love each other, or how picturesque the setting is, there is always a distance, regardless of emotional bonds or intimacy.

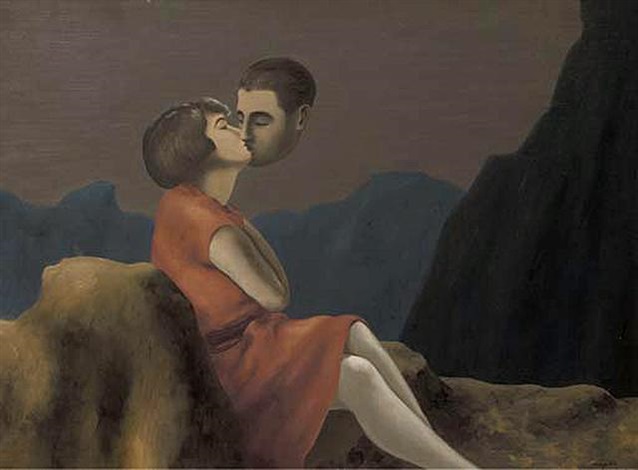

The two other versions of the Lovers are lesser known because they are in private collections. Also, without the white cloth, the figures seem less off-putting to the viewer, but they are also very thought-provoking in their own right. We may presume that the couple in this painting is the same as in the previous ones. The woman is wearing the same dress, and the angle of the man’s face is similar to that in The Lovers I. Actually, we cannot tell whether or not it is the same man without his body. What does it mean? That his head is with this woman, but his body and, therefore, his heart is with another? Is it a scene of betrayal or simply one about the improbability of a relationship between the two? Even though the lovers look more content as they embrace or kiss with nothing in between, could they really make it without the man’s body?

René Magritte described his paintings, saying, “My painting is visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, ‘What does that mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing, it is unknowable.”

Again, it is so often the case that masterpieces tend to show us whatever we like to see in them.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!