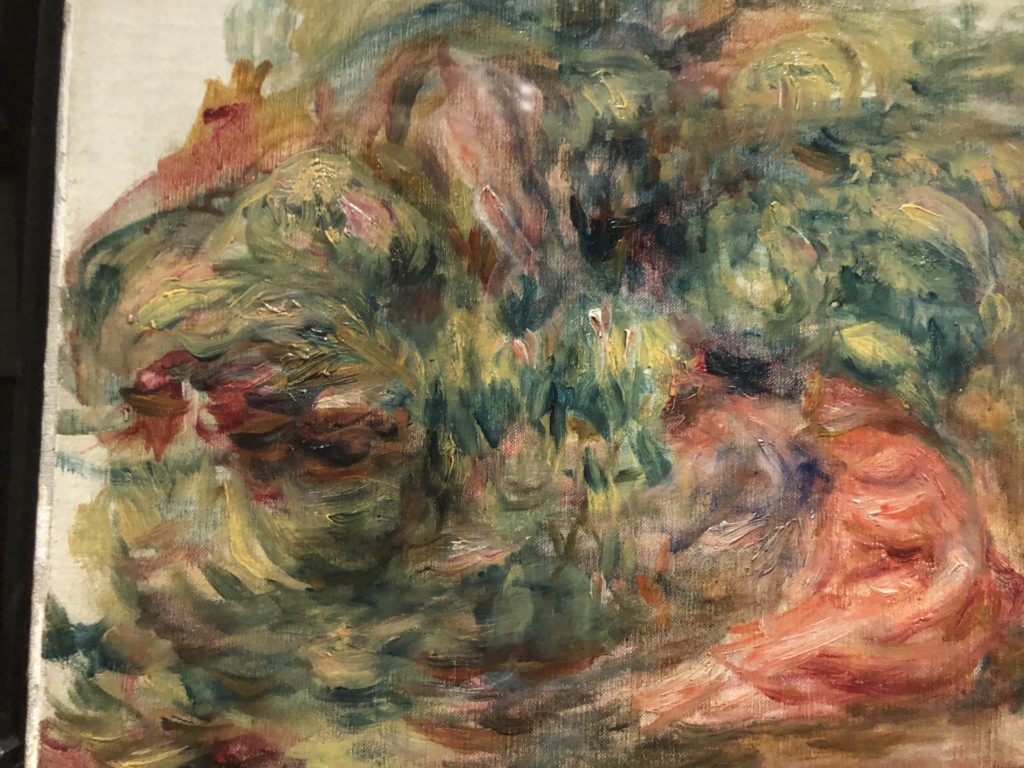

Renoir painted Deux femmes dans un jardin / Two Women in a Garden in 1919, the last year of his life. By this time, the artist’s vision had been failing him. And his arthritis had made it difficult for him to hold a paintbrush in his hand.

In Jean Renoir’s biography of his father, the younger Renoir wrote:

My father was waiting for me in his wheelchair. For several years he had not been able to walk. I found him much more shrunken than when I had first left for the Front. Yet the expression on his face was as lively as ever.

Jean Renoir was writing about the experience of seeing his father in 1915 after he had been wounded during World War I and sent home. When I think about the artist Renoir, this is one of the inspiring images that comes to mind. He could no longer paint with the precision he had enjoyed when he was younger. A lesser spirit would have been so depressed over the loss of some of his skills that he (or she) would have given up painting forever. Instead, Renoir discovered a new language with which to express himself. In doing so, Renoir inspires me to focus more on what I am able to do as an artist than on what I am not.

This small painting, seen behind a plate of glass, was exhibited in the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust. The painting was alone, like an only child, so there were no other paintings to distract one’s attention. Here is how the museum describes this painting’s connection to the Holocaust:

In a restitution ceremony at the Museum, Renoir’s Deux femmes dans un jardin was returned to its rightful owner—decades after it was stolen from her grandfather by the Nazis. The United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York presented Sylvie Sulitzer with the painting on September 12, 2018.

It is impossible to walk through this museum, which is located near Battery Park in New York City, and not be deeply moved. The survivors of the Holocaust become fewer in number as the years pass, but their stories and this horrific time in history can never be forgotten.

As for the painting, when I first saw it, I was bothered by it. The painting is called Deux femmes…, but I had difficulty finding the second woman. Everything on the canvas seemed so blurry as everything blended into everything else.

When I stepped back, I was able to notice a tree that I had not seen when I was standing closer to the painting. And then I began to appreciate the brushwork, the way some areas of the canvas were painted more thickly than others. And I saw the variation of color as well, and suddenly the painting came to life for me.

I think that Renoir’s color sense was a little off in his later years. In the book ‘Renoir and the Barnes Collection,’ written by Martha Lucy and John House, this issue was explored:

Many found fault with the palette. By the twentieth century, most of his work is built up around red as a dominating color key until, in his later nudes, the forms seem as red as boiled lobster, suggested the critic for the Art Digest.

Alfred Barnes preferred the later Renoirs to the earlier ones, so this quote needs to be understood in this context.

I am happy to have had the opportunity to have seen this painting in the museum and am even happier that after so many years, the painting has been returned to its rightful owner.