The (Real) History of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving brings families together to share rich meals featuring turkey, stuffing, and seasonal décor like pumpkins and warm autumn colors.

Errika Gerakiti 28 November 2024

Adele Bloch-Bauer was a wealthy socialite from Austria. One day, her husband asked Gustav Klimt to paint her portrait as an anniversary gift. But after the Anschluss of Austria, their family’s property was seized by the Nazis, including their artwork collection. 60 years later, a determined journalist discovers something in the Austrian Gallery’s archives that changed Maria Altmann’s life – the Klimt portrait that was rightfully hers. Altmann, Bloch-Bauer’s niece, sues the Austrian government in the United States. Find out the story behind Republic of Austria v. Altmann!

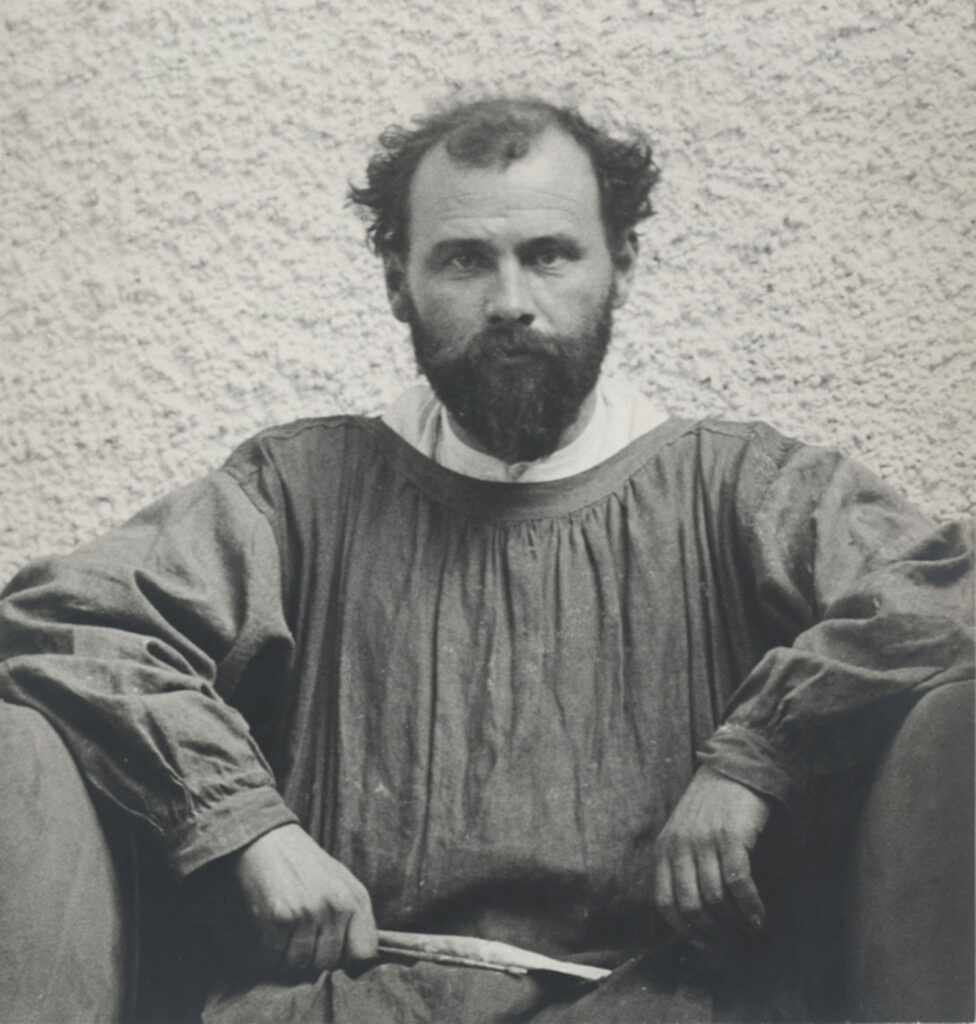

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was an Austrian painter known for his Secession masterpieces. His work admires the female body by evoking a bold, sensual eroticism. In a very decorative manner, Klimt used golden leaves and quirky geometric shapes to portray his subjects. Many art historians believe that his artworks display Egyptian, Minoan, Classical Greek, and Byzantine influences. Klimt visited the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, during the time he worked on this portrait. The architectural piece is heavily embellished with Byzantine mosaics of Empress Theodora.

Unsurprisingly, the artist was a founding member and the president of the Vienna Secession, established in 1897. The group rejected more traditional art styles and promoted young and foreign unconventional artists. He mentored the young Egon Schiele (1890-1918) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), also members of the Vienna Secession movement.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Photo of Gustav Klimt, 1902. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

A famous philanthropist, art patron, and wealthy socialite of the Viennese society, Adele Bloch-Bauer (1881-1925) sparked many controversies after her death. She led an avant-garde life enriched by her cultural and intellectual interests. Composers Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Richard Strauss (1864-1949) are just two of the many notable figures she hosted in her exquisite salon, among them were also journalists, artists, actors, and writers of the 20th century.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Photograph of Adele Bloch-Bauer. DailyArt Magazine.

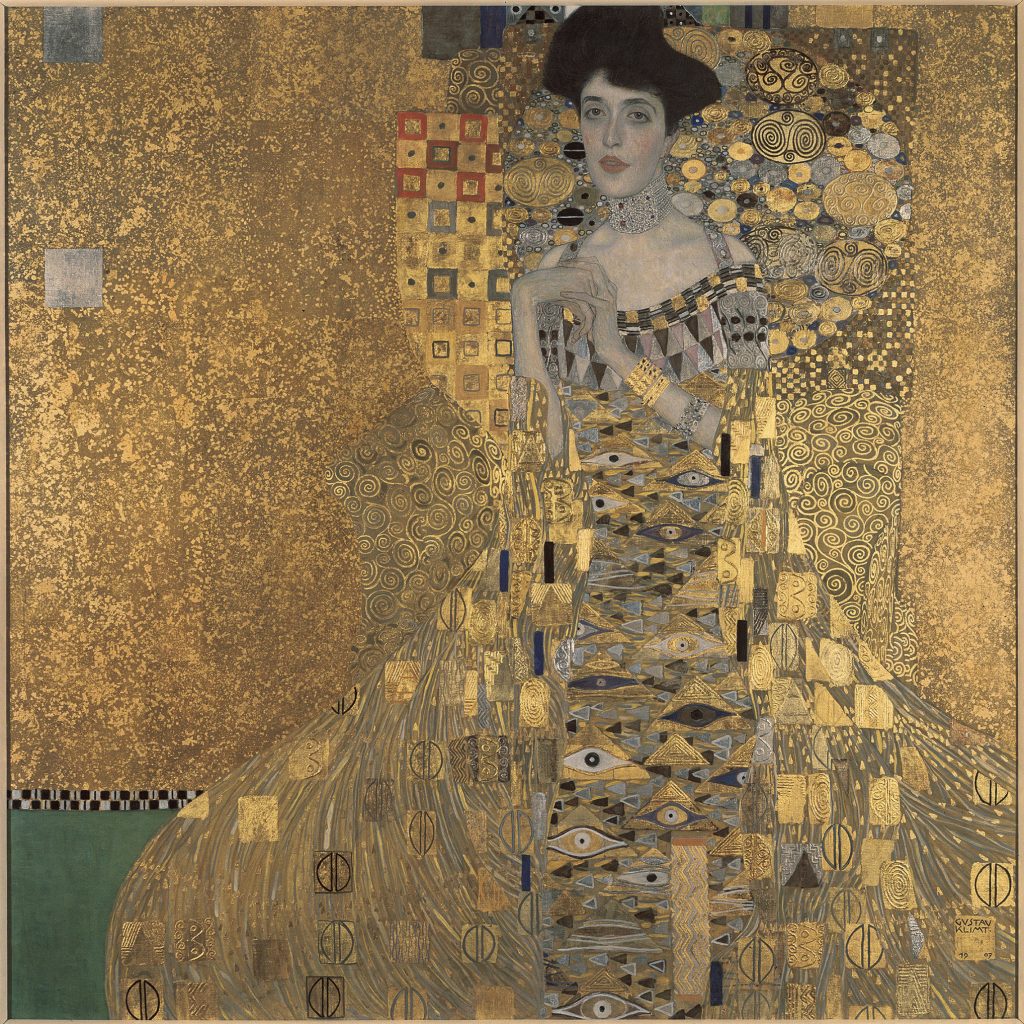

As a present for her parents’ anniversary, her husband Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, a wealthy Jewish industrialist, asked Klimt to paint his wife. The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I catches your eye immediately. The beautiful woman wears a golden gown. Her attire, representative of her social status, is heavily decorated with exotic symbols – eyes, triangles, eggs – which blend in with the intricate background. The darker tones contrast her fair skin and gleaming surroundings.

Bloch-Bauer, elevated by Klimt, leaves the earthly realm, reaching the golden heavenly skies. She is blushing: the pink tones in her cheeks speak of her youth. With her hands clasped timidly near her chest, the vulnerable posture suggests softness and sensuality. Regardless, Bloch-Bauer emanates a strong sense of feminine power and unshakable confidence. Light is truly shining through her. Klimt immortalized her beauty and grace masterfully.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie, New York, NY, USA.

Rumors about an affair between the artist and the model leave room for interpretation and call into question the emotional meaning behind the art. Some argue that in Klimt’s Judith and the Head of Holofernes, Bloch-Bauer is the erotic heroine. In both paintings, Judith and Bloch-Bauer seem “beheaded” – an effect rendered by their elegant neck jewelry.

Bloch-Bauer’s Klimts hung in her private apartment in Vienna.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Gustav Klimt, Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Austria.

Maria Altmann (1916–2011), Bloch-Bauer’s niece, remembered the visits to her aunt’s house, where the portrait was displayed. After the Nazis invaded Austria in 1938 and seized her family’s property, including the Klimt paintings, she fled from the country to the United States and built a life in California.

The Nazi lawyer, Dr. Erich Führer, in charge of liquidating the family’s properties, sold four of the paintings to the Gallery and Museum of the City of Vienna and kept one for himself. The immediate fate of the sixth work is unknown.

Hubertus Czernin, an Austrian journalist, revealed in 1998 that the Austrian Gallery wrongfully owned valuable artworks stolen by the Nazis or expropriated by the Austrian Republic after World War II. According to a law passed in 1946 by the Austrian government, all transactions influenced by the Nazi ideology are declared null and void. But because the paintings were considered highly valuable for the country’s cultural heritage, anyone who wished to acquire them needed to obtain the permission of the Austrian Federal Monument Agency. Allegedly, the Gallery and the Federal Agency coerced Jews to donate art pieces in exchange for export permits for other artworks. Some argue this extortion.

Two years later, Altmann’s brother hired a Viennese lawyer to locate the masterpieces and ask for their return. In her will, Bloch-Bauer mentioned that she wished to give the Austrian Gallery the six Klimts. The family’s lawyer agreed to donate the paintings to the Gallery to obtain export permits for other works from the family’s collection. However, contrary to what the Gallery reported at the time, the paintings were her husband’s and not hers. Thus her will was not enforceable in this context. On the other hand, Ferdinand left the Klimt paintings to the Altmann children in his will.

The Austrian government passed a new set of restitution laws soon after Czernin published his discoveries. A committee of Austrian officials decided to give Altmann some Klimt drawings and porcelain settings that the family had donated in 1948 but refused to return the five sought-after paintings.

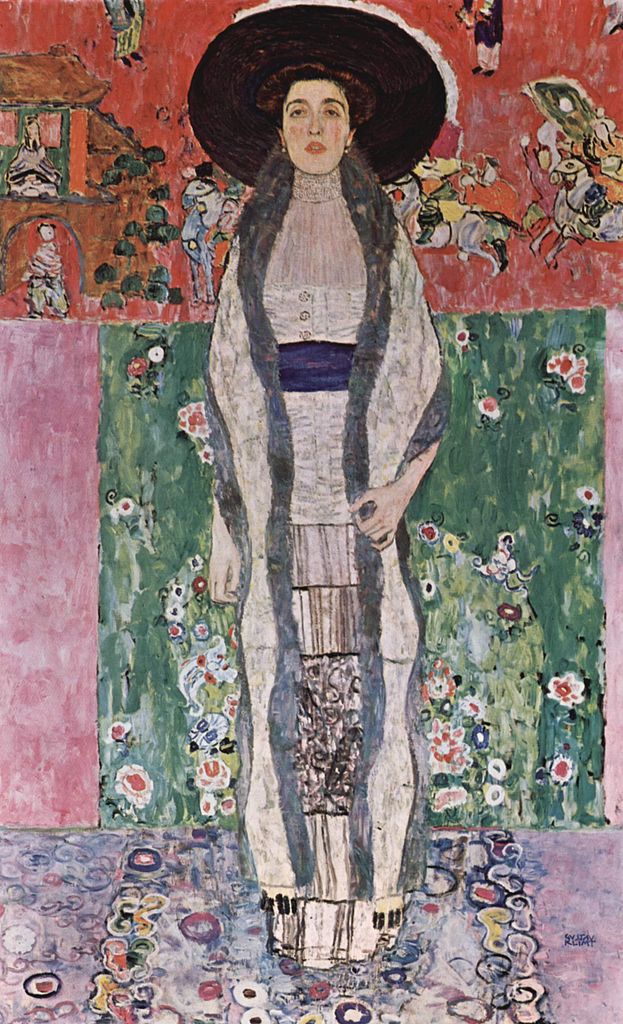

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912, private collection. Wikimedia Commons.

Altmann was committed to retrieving what was rightfully hers. She initiated a lawsuit in Austria against the government to recover the paintings. In Austria, the costs to sue are determined by a percentage of the recoverable amounts. At the time, the five Klimts were estimated at a value of $135 million, accounting for a fee of over $1.5 million. Although she requested a waiver, which reduced the fee to $350,000, still unable to pay the requested amount, Altmann dismissed the lawsuit and filed it again in the federal courts in Los Angeles, California. In the end, the case reached the Supreme Court of the United States.

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) of 1976 establishes the limitations and conditions on which a foreign sovereign nation (or its political subdivisions, agencies, or instrumentalities) can be sued in the US courts. In Republic of Austria vs. Altmann, the parties argued whether the FSIA does apply retroactively to claims that occurred before the enactment of the Act.

The petitioner, the Republic of Austria, produced two main points erected around sovereign immunity. Firstly, they argued that when the transaction between the Nazi lawyer and the Gallery occurred, Austria was protected by absolute immunity and that the FSIA cannot be applied retroactively. However, the Court recognized that retroactive application may not be as important in statutes concerning jurisdiction, like in this case.

Altmann’s lawyer, E. Randol Schoenberg, focused more on the “expropriation exception” of the FSIA. The exception dissolves the protection granted by sovereign immunity for states under the following circumstances: the entity has commercial ties to the US, and the case covers international law violations. The first condition was satisfied by the Gallery’s publishing and advertising activities within the US. And remember the extortion allegations brought up earlier? Altmann asserted that precisely those actions initiated by the Galley violated either customary international law or a 1907 Hague Convention. On top of this, there was another catch: the FSIA applies to conduct before the 1976 Act or the 1952 “restrictive theory” adopted by the US but to not country status.

In the FSIA, some language indicators suggested that Congress wished to apply this Act retroactively. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Altmann, allowing her to continue her venture into recovering the paintings. The Court wrote that “[The] language suggests Congress intended courts to resolve all such claims ‘in conformity with the principles set forth’ in the Act, regardless of when the underlying conduct occurred.”1

Altmann agreed to binding arbitration in Austria. If you are not familiar with this legal term, arbitration is a procedure in which one or more arbitrators decide the outcome of the dispute. The arbitration needs to be consensual, neutral, and confidential. In 2006, Altmann won the five Klimts. Victory! She died a few years later at the age of 94.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Photograph of Maria Altmann and E. Randol Schoenberg, right, speaking to Michael Govan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in front of Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 2006. AP Images.

The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, the most famous and valuable artwork, hit a world record at the time in a Christie’s sale. The artwork was auctioned at $135 million on a private basis. Bloch-Bauer’s disputed portrait is now at the Neue Galerie in New York. The other four paintings were sold at an Impressionist and Modern Art Christie’s sale in November 2006.

The motion picture Woman in Gold, initially released in 2015, describes the lengthy struggle Altmann went through to recover the paintings and explores her relationship with her lawyer, Schoenberg. The movie is starring Hellen Mirren as Altmann and Ryan Reynolds as Schoenberg. You should definitely give it a try if you are in the mood for a heart-melting story!

Republic of Austria v. Altmann: Still from Woman in Gold directed by Simon Curtis, with Ryan Reynolds, Helen Mirren, and Daniel Brühl, 2015. Robert Viglasky/The Weinstein Company.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann. Cornell Law School, 2004.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!