Apollo and Daphne in 5 Artworks

From Ancient Rome to the Renaissance and Rococo, the timeless appeal of the Apollo and Daphne myth spans centuries of artistic expression. The myth...

Anna Ingram 30 January 2025

Before 1901, Picasso’s subject matter was wide-ranging: urban scenes, contemporary society, religious depictions, and, once he came to Paris, the world of pleasure seekers. However, it was the death of his friend and fellow artist, Carlos Casagemas, that turned this colorful, hedonistic world into one of melancholia and isolation and one where he was to turn to a reduced palette of blues and greys inhabited by the destitute, the fallen and the maimed, forming what became known as Picasso’s Blue Period.

Casagemas and Picasso, close friends hailing from Barcelona, embodied a striking duality: while Picasso reveled in the vibrant exploration of life, Casagemas found himself mired in melancholy and depression—a poignant contrast to Picasso’s exuberance.

Their journey to Paris in October 1900, spurred by Picasso’s desire to showcase his work at the World’s Fair, marked a pivotal moment in their lives. Amidst the bustling streets of Montmartre, they indulged in the hedonistic pleasures of the Parisian scene. However, Casagemas’s infatuation with a model named Gabrielle soon overshadowed their escapades, disrupting Picasso’s creative flow.

As the new year dawned, Picasso ventured to Madrid, leaving Casagemas to grapple with his tumultuous emotions in Paris. Tragically, mere weeks later, news reached Picasso of his friend’s ill-fated attempt to end his lover’s life before turning the gun on himself. The profound impact of Casagemas’s untimely death reverberated through Picasso’s art, leaving an indelible mark on his work for years to come.

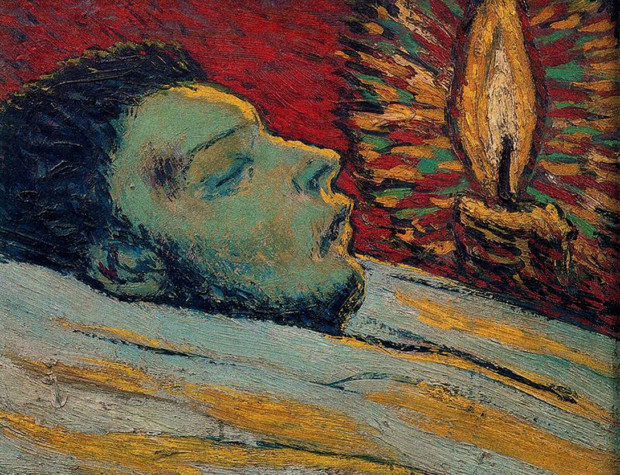

Upon Picasso’s return to Paris following Casagemas’s tragic death, he began the process of memorialization through his art. In this posthumous portrait, the stark depiction of the wound in Casagemas’s right temple reflects the harrowing details from the police report, underscoring the artist’s need to immortalize his friend’s memory.

Rendered with a haunting realism, the figure lies in a state of repose, bathed in the soft glow of candlelight—a poignant symbol of life amidst darkness. The subtle nuances of clammy skin tones further imbue the scene with an eerie poignancy, serving as a stark contrast to Casagemas’s own brooding persona.

Another iteration of this portrait, rendered in a somber blue hue, emerged later, resurfacing in The Funeral of Casagemas as a testament to Picasso’s ongoing exploration of grief and loss.

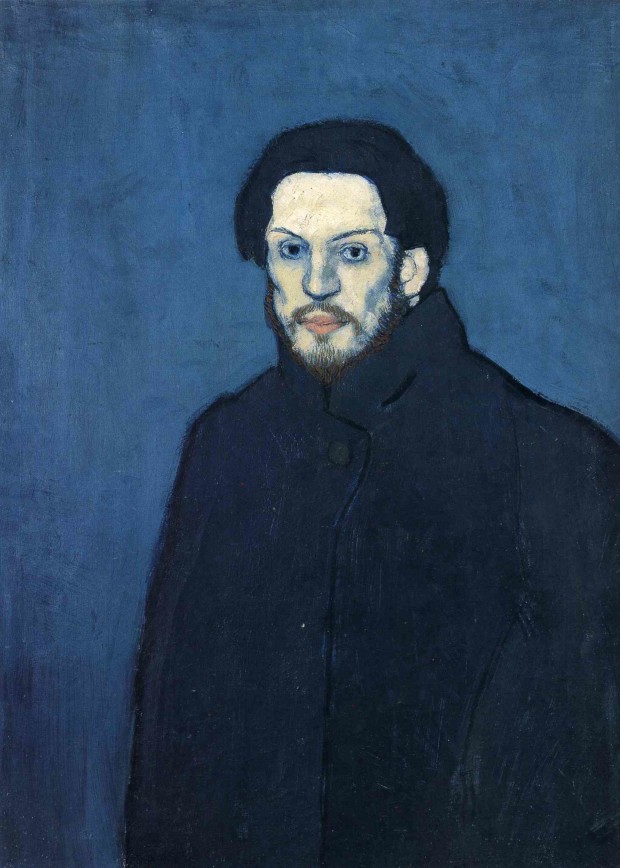

Aged 20, Picasso looks much older in this portrait; his face is gaunt, his eyes sunken and his beard unkempt. He looks directly out of the canvas, challenging us to ask him about his experiences. Wrapped in a large overcoat, he exudes an air of melancholy and isolation. His use of the blue tones here surround him but they are no comfort in this time of grief and hardship. This portrait was the start of Picasso’s Blue Period and encompasses all that he tried to achieve after this.

It’s intriguing to note the mirrored composition between Picasso’s self-portrait and the portrayal of the elderly woman afflicted with cataracts. During his time in Paris, Picasso’s encounters with the impoverished and marginalized left a profound impact on his artistry. This compassionate depiction of an elderly woman reflects Picasso’s conviction in dignifying the lives of the less fortunate. Amidst the melancholy hues of his Blue Period, this painting serves as a poignant commentary on the hidden struggles within society. Notably, the elongated forms and the somber attire of the woman resonate with Picasso’s own aesthetic and personal experiences, further emphasizing the depth of empathy captured within the canvas.

Upon returning to Barcelona in 1902, Picasso began exploring themes revolving around the dichotomy of love and tragedy, as he conveyed in a letter to his friend Max Jacob. The profound impact of Casagemas’s death, attributed to matters of the heart, and the subsequent loss of his own mother upon learning of her son’s demise, undoubtedly weighed heavily on Picasso’s mind. In his artwork initially titled A Saint-Lazare Whore and a Mother, Picasso grappled with these conflicting emotions.

However, as the composition evolved, culminating in the piece now known as Two Sisters, Picasso’s vision transformed. The tender portrayal of the two figures embracing suggests a shift towards themes of comfort and solace. Rendered in ethereal blue tones reminiscent of religious iconography, the painting exudes a spiritual aura, with luminous light softly illuminating their faces against a shadowed backdrop. Through the veiled heads and bare feet, Picasso evokes the solemnity of a Renaissance religious tableau, skillfully capturing the essence of grief. This pivotal work from Picasso’s Blue Period provided a profound examination of sorrow, laying the groundwork for his future masterpieces.

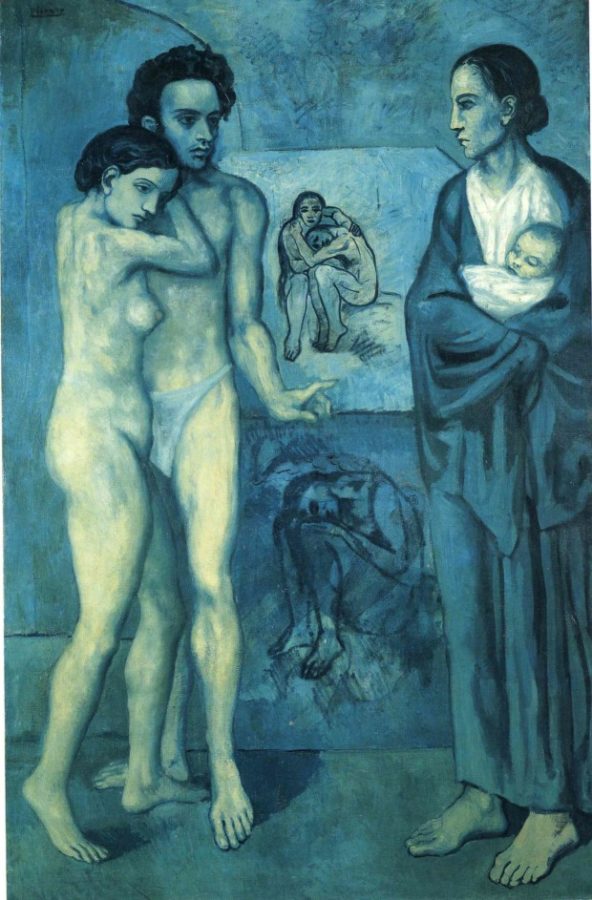

Numerous iterations and preliminary sketches paved the way for Picasso’s ultimate homage to his friend: La Vie – The Life. In a symphony of visual artistry akin to a musical composition, Picasso skillfully combines various elements of his craft to captivate the observer. On the left, Casagemas and Gabrielle are depicted, their bodies entwined yet emotionally distant. Despite their physical proximity, a palpable chill permeates their icy skin tones, symbolizing the emotional chasm between them. Gabrielle’s reluctance to wed Casagemas, attributed in part to his congenital impotence, is hinted at by Picasso’s portrayal of him semi-nude, juxtaposed with Gabrielle’s naked and forlorn figure. Their unfulfilled desires are poignantly underscored by Casagemas’s tender gesture towards the mother and child, a poignant symbol of familial love that eludes them both. Between these two pairs, a canvas portrays an embracing couple, enveloped in a poignant embrace of pure melancholy. This tableau of heartache reflects Picasso’s profound grief over the loss of his dear friend, inspiring a torrent of blue hues that would define his signature style and propel him forward as an artist, imbuing his work with unparalleled depth and emotional resonance.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!