A Fire in His Soul: How Paris Changed Vincent van Gogh

In his new book A Fire in His Soul, Miles J. Unger gives us Vincent van Gogh as we’ve never seen him before—abrasive, intransigent, egotistical,...

Ledys Chemin 21 February 2025

From the dawn of civilization, rivers have been the crux of human life. Most great cities are built around rivers. We use them for sustenance, transportation or simply to have a nice stroll and a good time. Throughout the ages, artists found inspiration in rivers, portraying their many faces in paintings. But how many faces can a river have?

For the Hudson River School painters, a landscape is never merely a landscape. In The Oxbow, Thomas Cole presents a bend in the Connecticut River after a thunderstorm. The painting is divided into two distinct parts. On the left, we have a section of the forest that is untouched by man. Nature is wild and untamed and possibly dangerous. On the right side, we see something completely different. Settlers overtake the landscape creating an order. There are cultivated plots of land, grazing animals, and small boats sailing on the river. Mankind put nature to good use, making it productive and useful.

Vincent van Gogh found peace and inspiration in the countryside. Arriving in Arles in February 1888 he painted this lesser-known Starry Night. The painting is a love song with the color blue. Different shades match and mingle. The night sky reflects on the river, completely dissolving the horizon. The gas lights shine like the stars in the sky.

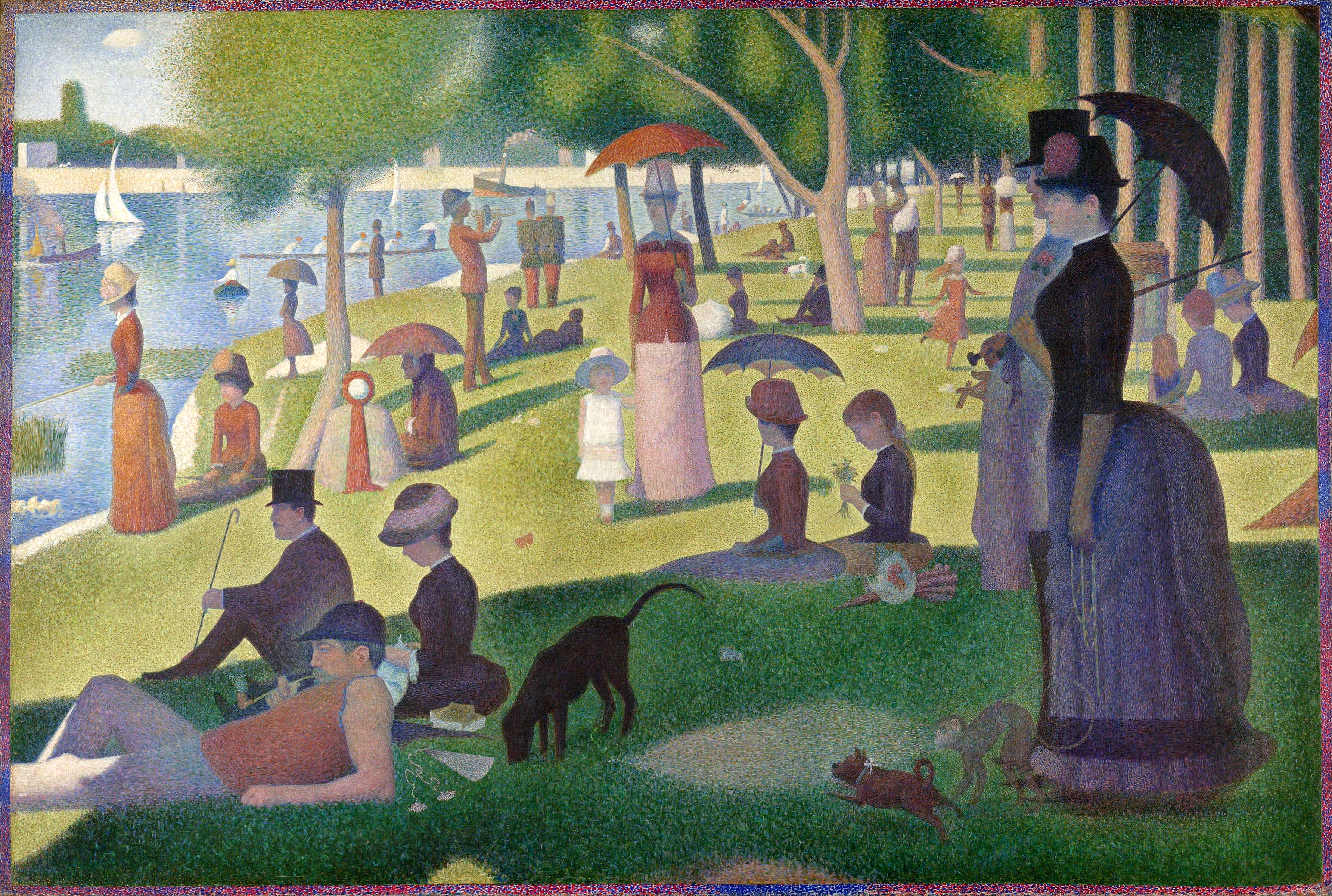

The small Grand Jatte is one of the islands on the Seine, which courses through Paris. During the 19th century, it was a popular destination for the high classes to relax and generally have a good time. On the canvas we see men, women, and children enjoying the sun on a Sunday afternoon. Georges Seurat used the pointillist technique for this painting.

But people are having a good time in London as well. In one of his many nocturnes, John Abbott McNeill Whistler presents a firework display in the Cremorne Gardens, near the Thames. Through planes of black and blues with splotches of luminous yellows, Whistler flirts with modernism, an intention to create a mood instead of a realistic depiction. True to the motto “Art for art’s sake,” the painting aims to just be aesthetically pleasing without having any didactic or moral purpose.

Throughout history, rivers often mark turning points in major historical events. Like Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon river, which led to his rise in power in ancient Rome, Emanuel Leutze commemorated a significant event in the American Revolutionary War.

Washington crossed the Delaware river on Christmas night in 1776 and attacked the Hessian camp in Trenton, NJ. This led to a crucial victory for the Colonial army and rekindled hope for the revolutionary cause. There are many historical inaccuracies on the massive canvas, but that is beside the point. This is a work of art to rouse the patriotic spirit and succeeds in creating an iconic image of the first president of the United States.

Rivers are also used to mark rites of passage. The Fighting Temeraire was a heroic ship in British naval history, which played a significant part in the battle of Trafalgar in 1805. J. M. W. Turner painted it in 1839 when the warship’s technology was considered obsolete and it was being towed away to be dismantled. The ship is being towed in the Thames by a new steam-powered tugboat, marking the end of an era. The ship appears ghostlike, rendered with grays and blues which make the whole piece an allegory about technological progress.

Rivers have been used for their symbolic power in literature as well. In Tennyson’s poem, the Lady, struck by her mysterious curse, takes a boat and travels downstream. While she floats down the river, she sings her last song, but the curse is so powerful that she breathes her last before reaching Camelot. The trip marks a rite of passage from captivity in the tower to freedom, from life to death.

On the canvas, we see the moment when she loses the boat’s chain and begins her journey. John William Waterhouse diligently painted the lush landscape of the riverside.

The river Styx, perhaps the most famous river in Greek mythology, formed the boundary between the land of the living and the Underworld. In Dante’s Inferno, the poet, along with his guide Virgil, crosses the river. Eugène Delacroix painted this scene literally made in Hell for his first painting in the Parisian Salon. The waters are teaming with the souls of the damned grabbing at the boat to escape. We see that the boat has become unstable as Virgil steadies Dante. In the backdrop, the City of the Dead is up in flames. In true romantic fashion, the painting is imbued with emotion. Theodore Gericault’s masterpiece The Raft of the Medusa served as an inspiration for the figures of the damned.

The importance of rivers for the flourishing of human civilization sparked the tradition of personifying the bodies of water with human attributes, essentially creating river gods. This began in ancient Greek art but continued in European painting and sculpture as well.

In The Four Continents, Rubens presents the four continents that humanity had discovered at the time, paired with what he deemed the most important rivers in each of them. There is Europe with the Danube, Asia with the Ganges, America with the Rio de la Plata, and Africa with the Nile. Sadly, the painting acknowledges the colonial views of Europeans at the time, with Europe sitting literally higher than the others. Today, we can still enjoy it while being aware of the historical context that created it.

So, how many faces can a river have? Quite a lot, actually. Rivers appear in most if not all genres of painting, marking great historical events and flowing ever forward to show progress or simply offer a few moments of relaxation.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!