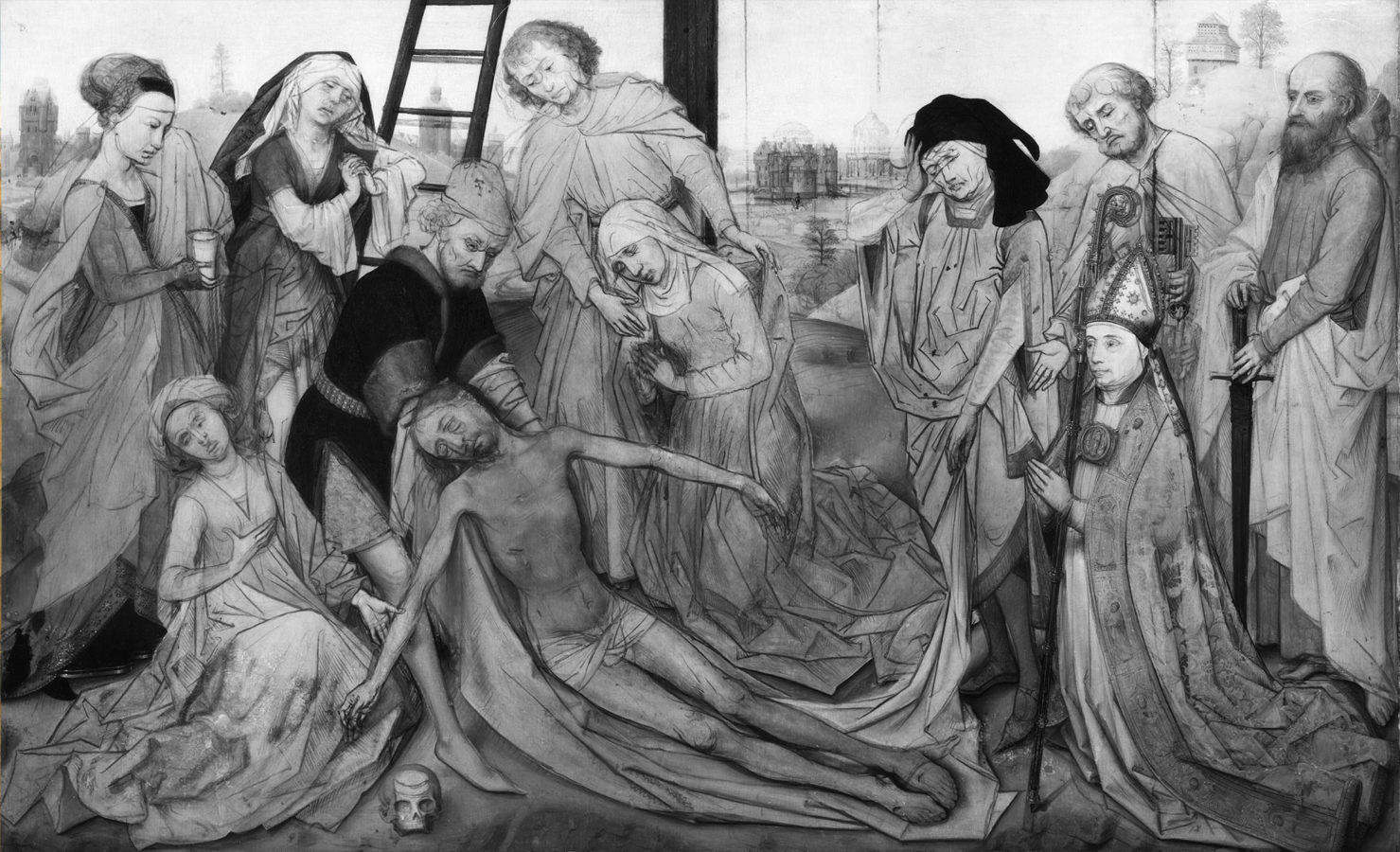

Rogier van der Weyden has a very special place in my heart because the first art historical essay that I had ever written at university was on him and his stunning piece from 1435, The Descent from the Cross (in Prado collection). This is why it warms my heart to hear that Mauritshuis Museum in the Haag has embarked on a fantastic and so needed project of a public restoration of Weyden’s another piece The Lamentation of Christ (c.1460-1464).

The project

Lamentation, which is the oldest painting in the collection (it was purchased for the Mauritshuis at a cost of 3,000 guilders in 1827 when it was believed it had been painted by Hans Memling, one of Van der Weyden’s pupils), is being restored in a temporary specially-built studio in the exhibition space so that all visitors have a chance to learn all about the scientific and art historical research into the work which still nowadays raises many doubts. Since it is clear that it was created with the help of Weyden’s pupils, the restoration will hopefully help answer such questions as to what extent the master himself had a hand in the work, how precisely was the painting made, whether the working method and the materials used were consistent with what Weyden usually used, or whether the preparatory underdrawing fits into the totality of his oeuvre at all.

Master’s hand or the hand of the workshop?

The removal of multiple layers of yellow varnish should allow a closer look at the painting’s superb details and the expressions of characters which, although strongly resembling those in the Prado’s Descent from the Cross (the last painting of the post), are clearly not as perfect (check out St Peter and St Paul on the right) and the figures seem to be rather disconnected from one another. On the other hand, if we examine Christ’s body, we see that it’s executed with extraordinary subtlety: would this mean that it painted by the master himself? It seems plausible to me that the most important figure of the composition was reserved for the master while the pupils practiced painting other figures in the master’s style, repeating Weyden’s inventions (especially the group compositions of crucifixions) in other works until the early sixteenth century, since after Rogier van der Weyden’s death in 1464, the workshop was continued by his son and grandson.

An Italian counterpart

Not only the visitors can ask questions and see the restorers at work, but also they have a chance to compare the work with another Weyden’s piece, which normally can be found in the Uffizi in Florence, the Entombment of Christ from c.1460. Entombment is a rather unusual subject in Flemish art, but it was more common in Italy and hence it is possible that when Weyden went in 1450 on his Italian tour (he was received as a celebrity), he met Cosimo de’ Medici ‘il Vecchio’ (the Elder) who later on commissioned from him an altarpiece panel for his Villa Careggi to the north of Florence. Although the panel is made of oak wood, which is a typical Flemish material hence the painting must have been executed in the Weyden’s studio, the plants and especially trees in the background look more Italian than Northern European. The composition of the scene is also Italianate and it was inspired by Fra Angelico‘s altarpiece painted around 1440 for San Marco’s in Florence, which was commissioned by Cosimo as well.

Emotions restored

Rogier van der Weyden, born around 1399 in Tournai where he was trained by Robert Campin, is regarded as a key Flemish painter of his day, second only to Jan van Eyck. He worked in Brussels from 1435, where he was appointed city painter a year later. Both van Eyck and van der Weyden were great innovators in the development of oil painting, rendering their paintings unprecedentedly lucid and vividly coloured with lifelike details, all made possible by flowing and more precise movements of the brush, which were granted by this new technique. While Jan van Eyck was unrivaled in creating the illusion of a real world, Rogier van der Weyden added to this naturalism an element which changed the Netherlandish Renaissance painting forever: he began painting emotions (I am always profoundly moved by the way he painted tears), which thanks to such worthwhile projects as the one at the Mauritshuis, are finally clearly visible and accessible to all.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”3848005514″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/51xJ3g4HvFL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”135″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1857598474″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/51LvLGA2UpL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”140″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1904449247″ locale=”UK” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/51RQF71VC1L.SL160.jpg” tag=”dail005-21″ width=”119″]