The Evolution of Art During the Fall of Rome

The Fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE was a pivotal moment in history, signifying the end of a dominant civilization that had reigned...

Maya M. Tola 16 October 2023

Floor mosaics are one of the most well-preserved and widespread objects of Roman art. They were found throughout the Roman Empire from Britain to Mesopotamia. Mostly used in public buildings such as Roman baths and marketplaces, they were also used in places of worship like synagogues and churches.

Ancient floor mosaics were often made of tesserae, or tiny stone pieces. Glass tesserae were used sparingly, typically for more unusual colors that were difficult to find in natural stones. Mosaics were a costly investment thus, a lot of attention was given to the themes, designs, and personal tastes of the owners. Scenes from Greek and Roman mythology were popular because they were timeless and familiar, other themes included hunting, fishing, wrestling, and animals.

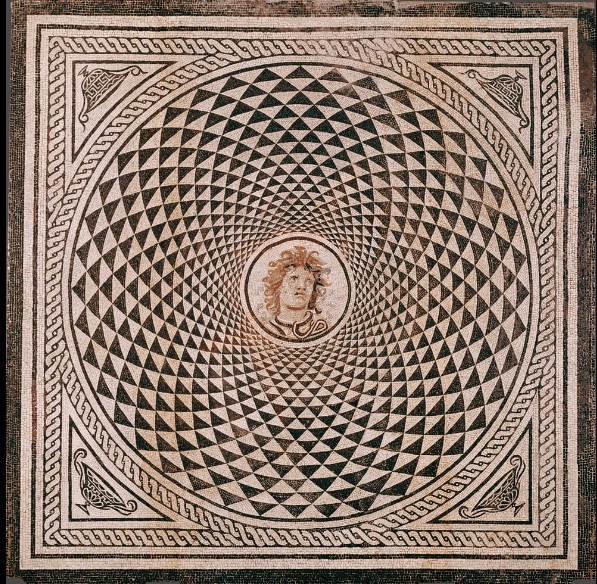

Mosaic floor with the Head of Medusa was discovered on the floor of a Roman villa in 1910 in Rome. At the center of this mosaic floor is the bust of the gorgon, Medusa. The Greek representation of Medusa as a monster had been replaced with a more human-like figure by the Romans around 100 CE. Medusa’s snake-like hair was replaced with wild curls and she was represented like the Hellenistic Kings and Alexander the Great, with her wind-blown hair and turned head.

In this mosaic, Medusa is portrayed in a shield of concentric black and white triangles which create an optical illusion of continuous motion. The circle is enclosed in an outer square with kantharoi or drinking cups at the corners. The guilloche pattern or braided pattern border the circle and the inner part of the square. The head of Medusa on a shield motif appeared frequently on Roman mosaic floors. The design is inspired by Athena’s aegis, the scaly protective cloak decorated with Medusa’s decapitated head.

In Greek mythology, Medusa was a fearsome monster who could turn onlookers into stone. She was beheaded by Perseus who presented her head to his patron goddess Athena, daughter of Zeus. The Gorgon’s head was a popular apotropaic device in Greek art, supposedly used to ward off evil influences or bad luck. Even though the Romans used the Gorgon image for decorative purposes, she continued to be regarded as a protective symbol.

The mosaic was discovered in 1912 in Saint-Romain-en-Gal, France, and originally decorated a room of approximately 15 feet by 20 feet. Orpheus was a musician, poet, and prophet in Greek mythology. He learned to play the lyre from Apollo, the sun god. His music was appreciated by everyone, including the gods, animals, and trees. In the mosaic, there is no reference to Orpheus’s music, but the visitors were familiar with the mythological figure. Perhaps, the mosaic adorned the floor of a room for entertaining guests.

The floor mosaic of the Sea Goddess Tethys is currently located on the university campus of Harvard Business School. The mosaic comes from the ancient Roman city of Antioch, present-day Turkey. At its center is the bust of the goddess, Tethys, surrounded by 23 sea creatures of different shapes and colors. The mosaic was excavated in 1939 by a team of archeologists from Harvard University, the Worcester Art Museum, Princeton University, and the Baltimore Museum of Art. The Tethys mosaic was originally located in a pool in a bath building.

The sea goddess Tethys was not an unusual subject for Antioch since the city was located on several bodies of water, and visual art from the area often included marine themes. Although the sea creatures around Tethys are not entirely of a naturalistic depiction, they have been identified as dolphins, squid, goatfish, sea bream, and percoid fish (such as bass). The ancient floor mosaics were largely made of stone tesserae, in the Tethys mosaic both stone and glass pieces are used especially for marine creatures.

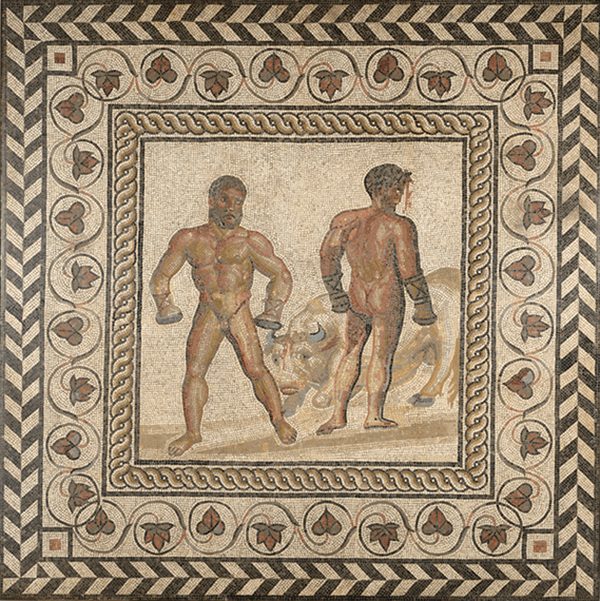

Roman artists used mosaics to tell a story. They narrated the tales using key elements like objects, characters, or symbols that were familiar to the viewers. Mosaic floor with a Boxing Scene or mosaic floor with Combat Between Dares and Entellus depicts two men wearing nothing but their boxing gloves. Ancient Roman athletes often competed in the nude. In the scene, one is bleeding from the head and the bull in the background is also bleeding.

This scene is from Book V of Virgil’s Aeneid which refers to the Trojan hero, Aeneas, hosting funeral games in Sicily to commemorate the passing of his father. In the boxing match between the Trojan, Dares, against Entellus, a Sicilian, Entellus won the match. Although the underdog, Entellus became so angry with Dares that he had to be stopped from killing him. Entellus was awarded the bull which he sacrificed by shattering its skull.

The artist has captured the scene where Dares turns away in defeat and the bull sinks to the ground. Excavated in 1900, this mosaic adorned the floor of a wealthy Roman in Villelaure, France. It was normal for wealthy homeowners to use art to display their wisdom and knowledge and as a way to show off their wealth to visitors.

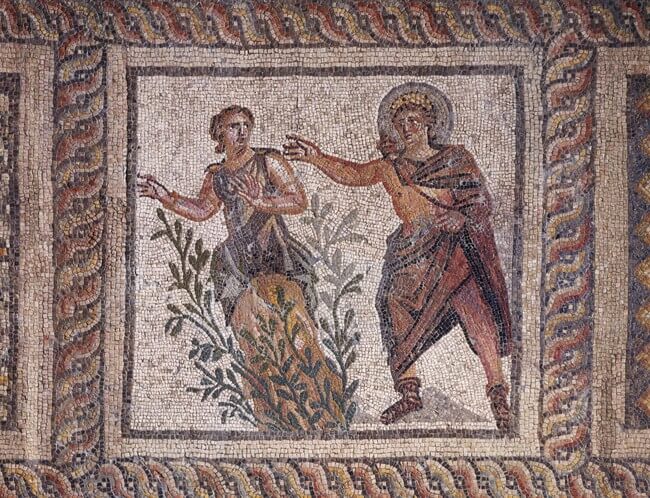

The mosaic floor with Egyptianizing Scene was found near Prima Porta, north of Rome in 1892. It was one of several mosaics found in a villa complex. The mosaic is made of stone and glass tesserae. Although the real interpretation is unclear, the two figures in the central panel wear Egyptian dresses, the man standing on the left has been identified as a priest, making an offering to the seated figure, regarded as the goddess Isis. The Romans were highly fascinated by Egypt as a land of great wealth and antiquity. However, the surrounding geometric and floral designs are typically Roman.

The mosaic floor with Bear Hunt was excavated in 1901 in a vineyard in Baiae, Naples. According to the archeologists at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples, it may have decorated the great room at a bathhouse and is believed to have little artistic value. The central panel of the mosaic depicts the scene of a bear hunt. Three hunters can be seen driving five bears into a net tied to some trees. The fourth hunter which is missing from the above mosaic appears on a panel which is now part of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples.

The hunters stand with their legs bent and arms extended forward. Three of them hold staffs in their hands and are beardless. Two of the figures are accompanied by inscriptions identifying them as Lucius and Minus. A cord in Minus’s left hand suggests that he is tying the net to a tree. The bears move in the direction of the net and their mouths are open.

The scene is bordered with a colorful double guilloche pattern of green, yellow, red, and black stone tesserae. Outside the guilloche, at right, there is a long, straight, vertical laurel festoon tied at the center by a ribbon. A third, outermost border consists of a decorative form called exuberant acanthus rinceau inhabited by fruit, armed cupids, and the protomes of real and imaginary animals, including a horse, a panther, and a griffin. The two preserved corners are adorned with large acanthus-enveloped faces referring to the Four Seasons, a common feature in Roman mosaics.

On one of the four panels in Naples, a third and smaller face emerges from the acanthus rinceau. This face was likely located beneath and to the left of the hunters, and its frontal orientation suggests that it may have originally marked the midpoint of the entire mosaic, which must have included at least one additional scene.

Hunting was a popular activity with Roman aristocrats. Other large hunting floor mosaics include the mosaic from the Gardens of Licinius in Rome. Emperor Hadrian (117-138) hunted bears in Greece and Asia Minor. He even composed a poem on his success as a hunter. Bears were hunted throughout the Mediterranean world, where they were trained as well as slaughtered. The theme of hunting was a particular favorite of royals who sponsored spectacles with wild animals in the amphitheater.

The Worcester Hunt Mosaic was excavated from the pavement of the villa Daphne in Antioch. At the center stands a hunter surrounded by wild animals in a pattern much like that of an oriental carpet. The hunter’s are on both foot and horseback and attack a variety of animals with swords, spears, bows and arrows, which were weapons used by Parthians and Persians.

Mosaic of a Lion Attacking an Onager depicts a violent scene of prey and predator, the lion sinks its teeth into the fallen Onager, a wild ass. Blood spills out from the wound and falls onto the ground. There are two trees in the background and a body of water in the foreground. A single polychrome guilloche runs below the main scene. The mosaic is formed from tesserae of colored marble, stone, and glass set into a bed of mortar. Although the scene is complete in itself, it could also be part of a larger floor mosaic depicting several scenes.

The panel was found on the floor of a luxury villa in Hadrumetum (present-day Sousse, Tunisia). Images of animals preying on other animals were quite popular in the Roman mosaics of North Africa. Second-century Tunisia was an economically and politically flourishing part of the Roman province. A larger number of mosaics have survived from Tunisia than any other part of the Roman Empire. In his review of the exhibition of Roman floor mosaics at the Getty Villa, Christopher Knight called it “conflict chic”.

With its ornamental framing and decorative images, the mosaic creates the effect of a luxurious carpet. It depicts numerous fish, fowl, and animals, as well as two sailing ships. There are dramatic scenes of animals being preyed upon and other scenes of wildlife peacefully coexisting. It is humans that are missing from the scenes. The significance of the central panel with various animals remains unclear. Animals like rhinoceroses and giraffes were rarely depicted in ancient art. Besides natural animals, the mosaic also features the mythological creature, Ketos, a sea monster, which may represent the mysterious ocean that surrounded the ancient world.

However, the lower part of the mosaic with its marine life is the most surprising part: the presence of big and small fish, the two ships, the absence of a broad frame, the lack of symmetry, and the glassiness are contrary to the general logic of panel construction. The marine panel stands out because it is not part of the scenery but an independent work. Perhaps, the owner of the villa was a marine merchant and the sea imagery was important to him.

Excavated in Antioch, this mosaic of a Vine Scroll Border with Peacocks is one of six fragments of a border of a large floor mosaic. This is a computer reconstruction of how the mosaic may have appeared if joined back together. The mosaic depicts two peacocks and grapevines that grow out of an urn in the center. An inside border comprised of twisting ribbon in gray, pink, and yellow is set against a black background. The graded treatment of the colors and the dark background produce a three-dimensional illusion of a fluttering ribbon that mirrors the curves of the scrolling vine.

In the Roman world, peacocks were associated with immortality and eternal life. The overall effect of the mosaic with grapes and rosebuds is of abundance. Discovered in a private house in Daphne, the mosaic also has early Christian art motifs like the grapevine, peacocks, and the wine vessel. The mosaic was probably a reference to the beauty of God’s creation and a promise of salvation.

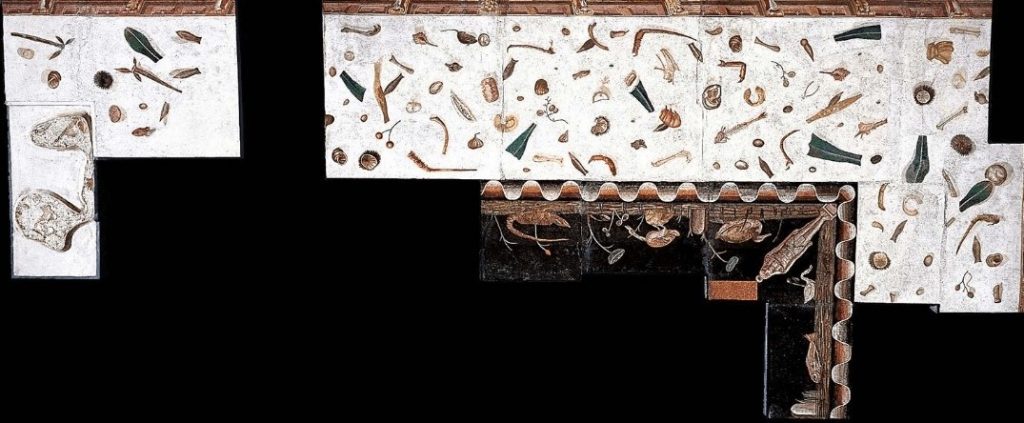

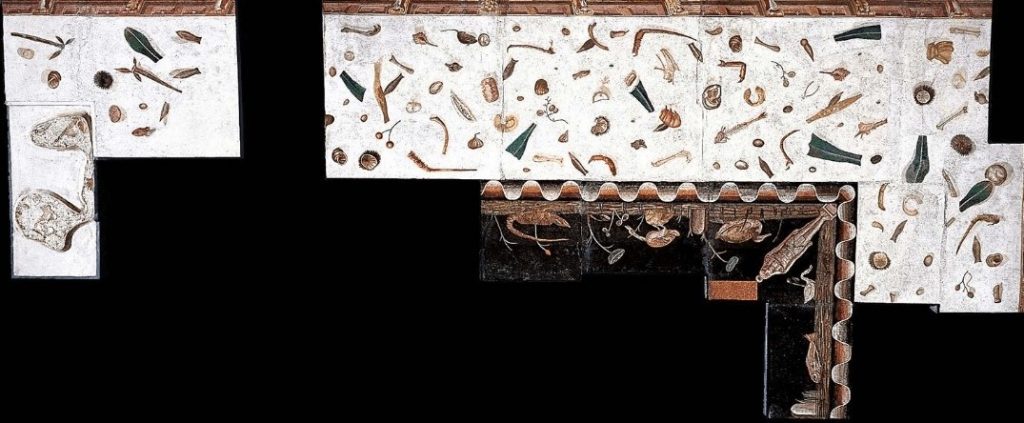

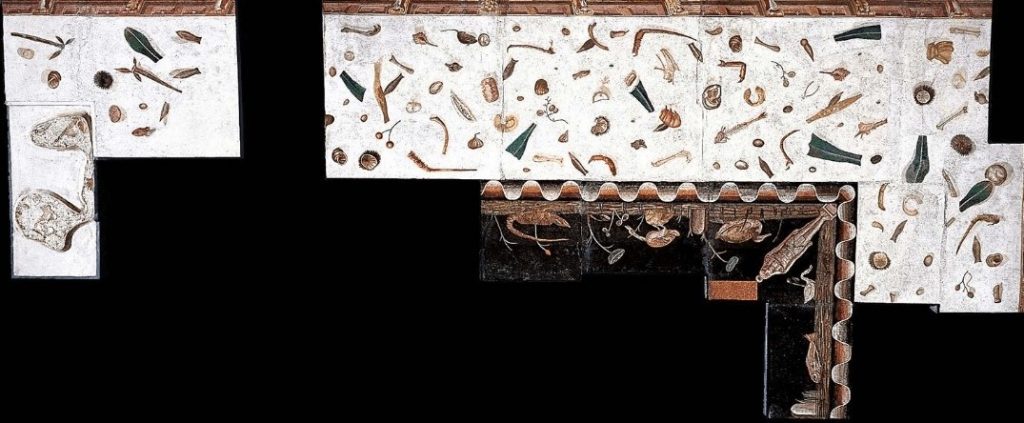

Cat Fighting Against a Cock, Ducks, Fish and Shells mosaic, was discovered in the House of the Faun, built during the 2nd century BCE in Pompeii, Italy. The mosaic comprises of three registers: the genre scene of a cat catching a cock, its feet tied with a red chord, the middle scene of a Nilotic painting, and the lower one is a still life.

The cat with black spots is depicted accurately, suggesting it is an Egyptian breed that was extremely rare in the Italian Peninsula in the 2nd century BCE. Along with the Nilotic painting, the mosaic suggests that there was already an Alexandrian influence on Roman mosaics.

Floor mosaic with a Gordian Knot is taken from a larger design found in Homs, Syria. It represents the famous knot, associated with Alexander the Great, and is a common motif found in Roman mosaics. Made of stone tesserae in white, red, yellow, black, and tan, the knot is enclosed within a circular sunburst border. This mosaic is a little more complicated than most depictions of the Gordian knot, which often depict only one or two layers of the knot, rather than the three shown here.

This mosaic floor panel was found in an olive grove at Daphne-Harbiye in 1937. Daphne was a popular holiday resort with the Romans. The wealthy residents of Antioch visited the place for rest and refuge from the heat and noise of the city. It was a place that was appealing to its patrons because of its luxurious surroundings. At the center is a panel or emblema with a bust of a woman wearing a floral wreath and a garland of flowers over her left shoulder. The woman is a personification of Spring, a season of rejuvenation.

The Academy of Plato or Seven Philosophers mosaic was created in the first Pompeian style. It portrays the meeting of seven Greek philosophers and orators of the classical period. From the left, they are identified as Heraclides Ponticus, Lysias, and Plato, who is pointing with a stick at a globe. The second to last figure on the right is Xenocrates and the last one on the right is Aristotle, holding a scroll in his hands and walking away.

In the background is the Acropolis of Athens with the Parthenon. There is a portal with two columns and an epistyle with four covered vases symbolizing: Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, and Music (or the Four Seasons of the year, or the positions of the Sun). The tree and a votive column with a sundial are typical of a mythological landscape without any specific geographic references. Created in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, the theme clearly refers to the literary and philosophical interests of the owner of the villa and probably derives from a late-Hellenistic model.

The mosaic of the Travelling Musicians was discovered at the Villa of Cicero, Pompeii between 1749 and 1763. It portrays a group of four characters, probably the metragyrtai or wandering beggars of the cult of Cybele. They are playing tambourine, cymbalists, and double flute as they go from house to house. They are followed by a child or a dwarf wearing a short tunic and playing a sort of horn. The three characters are wearing masks of the New Comedy, and the scene is probably based on one of Menander’s comedies entitled Theophorumene (The Girl Possessed by a God).

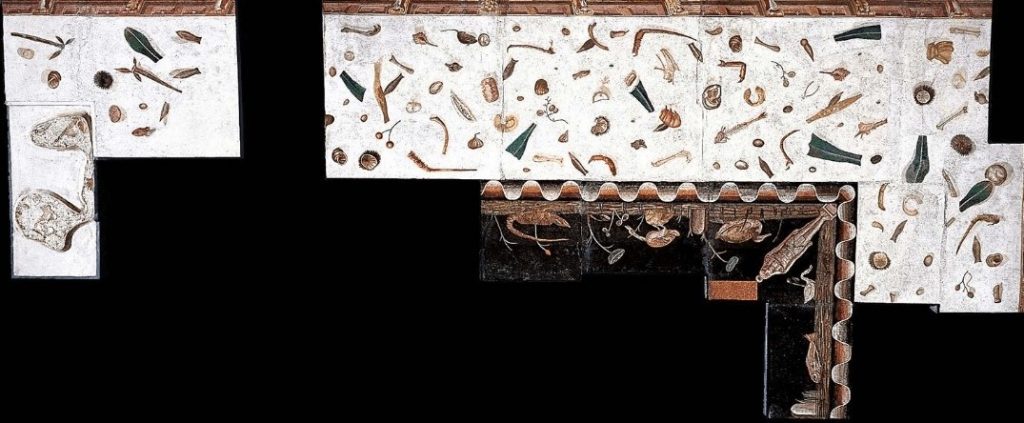

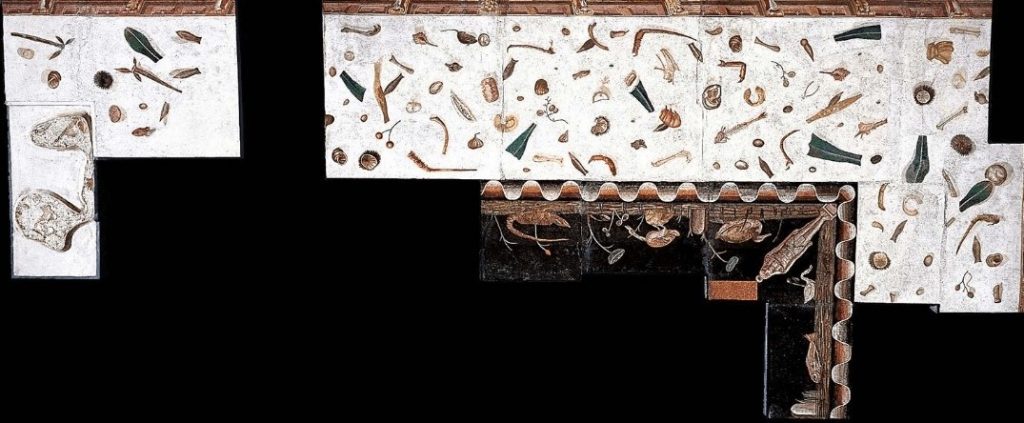

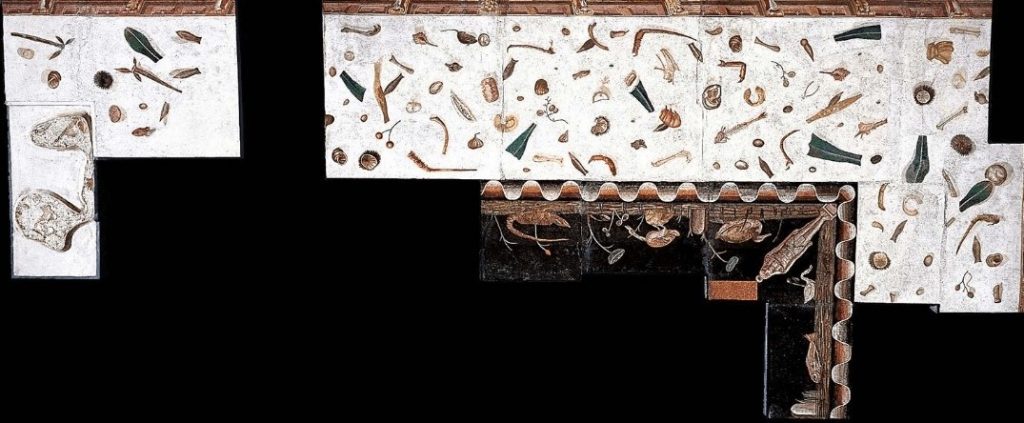

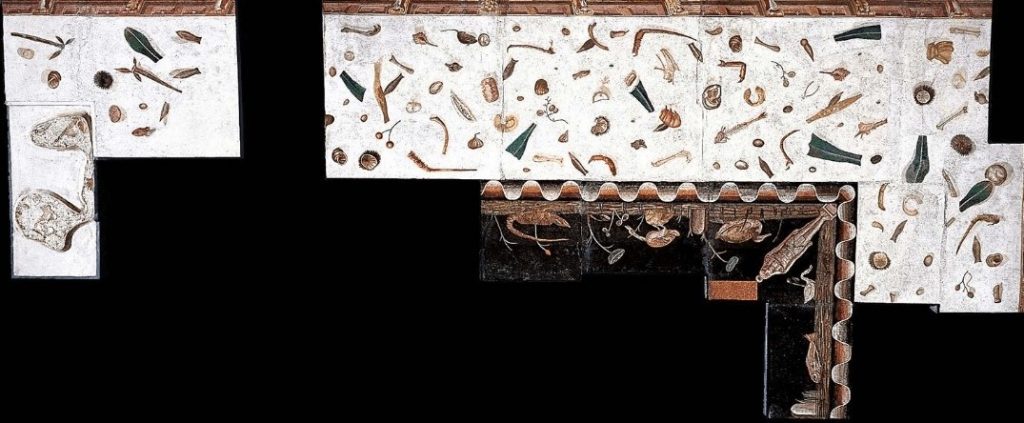

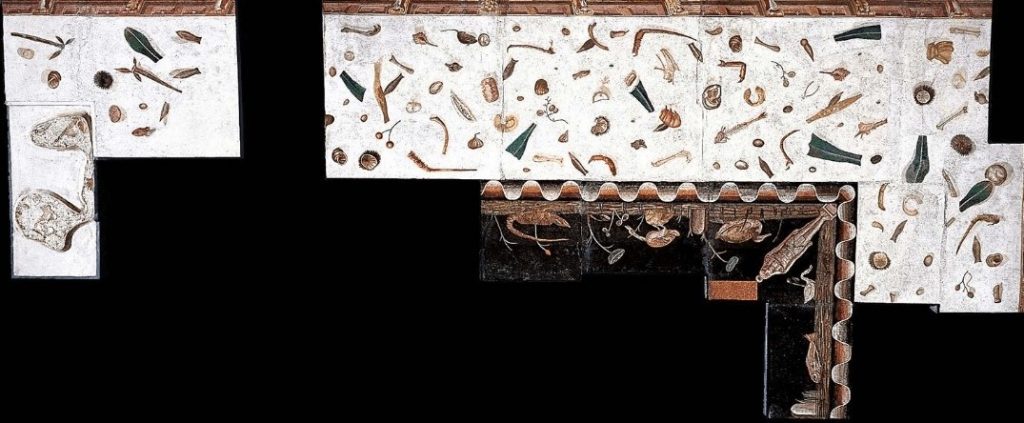

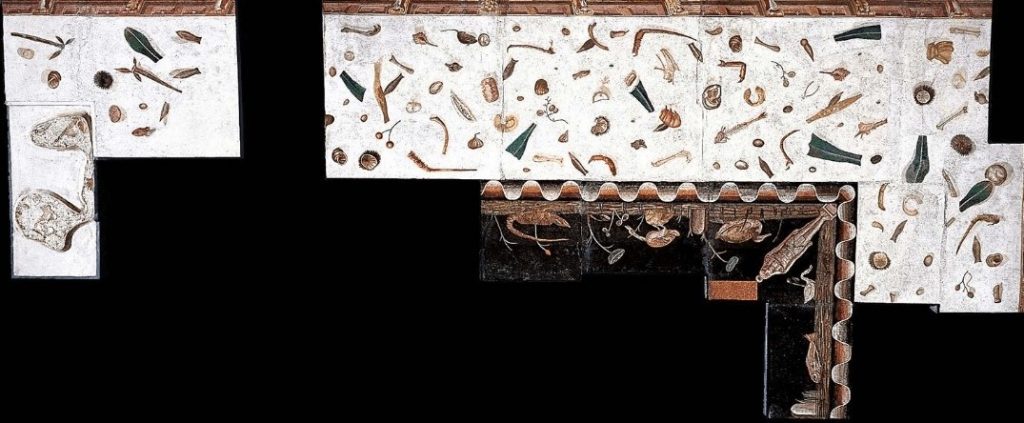

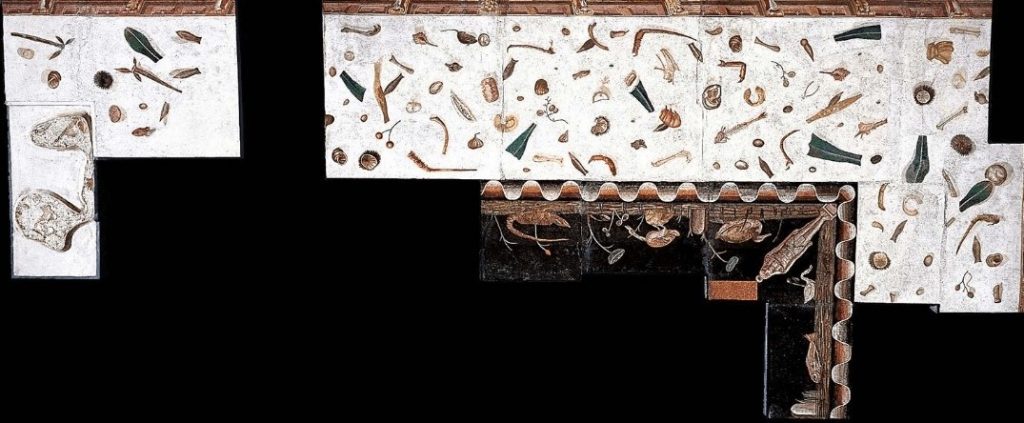

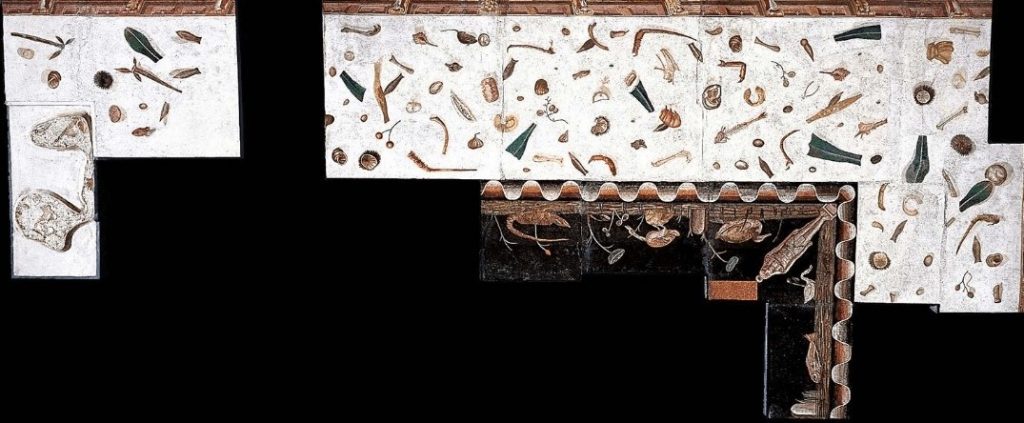

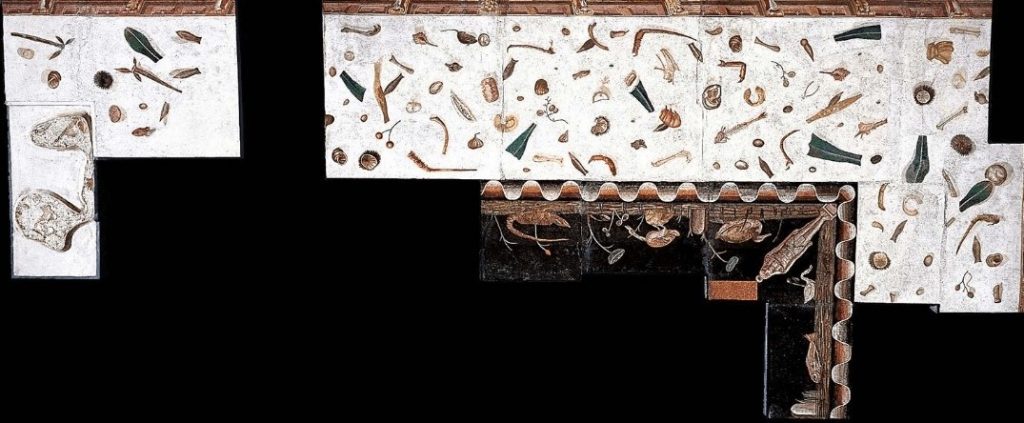

Asàrotos òikos mosaic was made of small pieces of glass and colored marble. It adorned the floor of the dining hall of a villa on the Aventine Hill, Rome at the time of Emperor Hadrian. The theme is known as asàrotos òikos, or “the unswept floor,” created in the 2nd century BCE by Sosos of Pergamon. On the mosaic floor, the design was recreated by artist Heraclitus, who signed his name.

The floor is covered with debris from a banquet and food waste that would normally have been swept away. The debris identified is fruit, lobster claws, chicken bones, and shellfish. There is also a tiny mouse nibbling at a walnut shell on the top of the mosaic. The discarded remnants of a meal are realistically depicted on a plain floor of white tesserae, thus playing a trick on viewers and encouraging them to appreciate the three-dimensionality of a two-dimensional floor surface. The entrance of the floor is designed with theatrical masks and ritual objects, and at the center is the scene of the Nile River.

The Portrait of a Woman mosaic was found in the tablinum, an open living room that could be curtained off from public view, in a house in Pompeii. It dates back to the Julio-Claudian period, the first half of the 1st century BCE (1-49 BCE). The portrait reproduces the features of a Pompeian woman of high rank: her face is framed by dark hair and tied up according to the style of the period. She is wearing pearl earrings and a pearl necklace with a pendant of gold and precious stones. The woman’s features are realistically depicted which suggests the importance of the mosaic for the owner of the house.

The majority of mosaics decorated the floors of private luxury villas and houses. Though, an expensive addition to the property, the mosaics required little maintenance and lasted a lifetime.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!