Masterpiece Story: Portrait of Madeleine by Marie-Guillemine Benoist

What is the message behind Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine? The history and tradition behind this 1800 painting might explain...

Jimena Escoto 16 February 2025

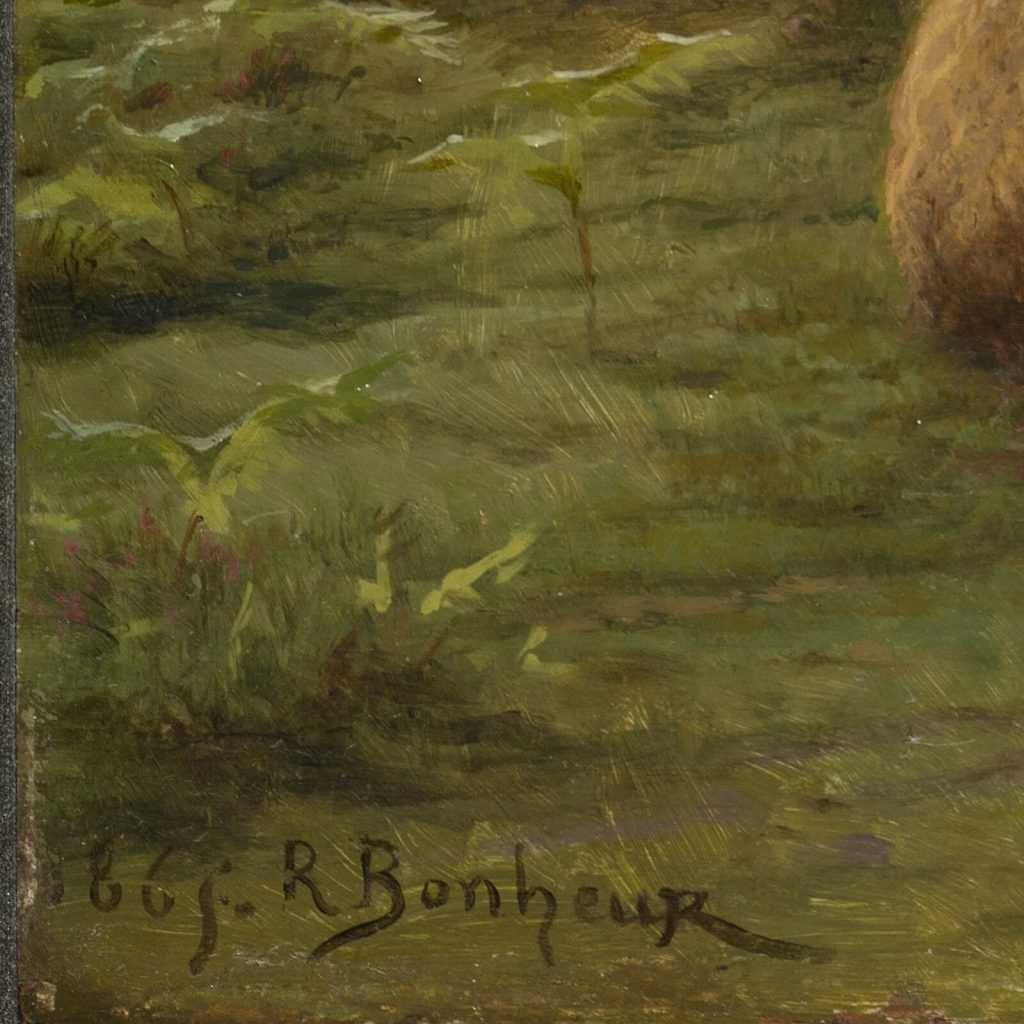

Rosa Bonheur was one of the most famous European artists of the 19th century, and she was definitely the most celebrated female artist of her time. Bonheur not only received recognition by the Paris Salon but was also awarded the Légion d’honneur (Legion of Honor), the highest decoration available in France for a non-military achievement. The reward was officially bestowed by Empress Eugénie of France to Rosa Bonheur in 1865 just shortly before or after Empress Eugénie’s commission of Sheep by the Sea. Bonheur’s acclaim was so renowned that it was not hindered by France’s borders as her reputation crossed the English Channel and gained Queen Victoria’s approval too. Rosa Bonheur was, therefore, internationally successful with a firm distinction as a master painter of animals.

Rosa Bonheur’s Sheep by the Sea is a sentimental painting of domestic animals. As the title indicates, it features seven sheep laying in a pasture by the seashore. Three sheep cluster together in the foreground, four sheep cluster together in the midground, and the sea and sky fill the background. The three foreground sheep are two ewes and one lamb. One ewe looks to the right in profile, one ewe looks to the viewer in full-face, and the lamb looks to the left in profile. The three foreground sheep present the three distinct positions of a sheep’s head. Their three distinct views add compositional interest and also display Rosa Bonheur’s observational and painterly skills.

The four sheep grouped together in the midground form almost a solid block of wool. Their bodies blend together and do not have the individual identities of the three foreground sheep. All four sheep’s faces are either hidden or indiscernible. Three of these midground sheep face the background, and one nestles its indistinguishable face against the meadow. While the midground sheep do not have any apparent interest as a single motif, they do add visual interest to the overall composition of Sheep by the Sea. They provide a sense of depth to the landscape by being depicted smaller and closer to the horizon. They essentially add linear perspective to the otherwise flat and unmeasured meadow. Also, the midground sheep create a balance with the craggy rocks emerging from the sea on the left side of the composition. The balance is further strengthened by a triangle formed by the three foreground sheep. This triangular placement unifies Sheep by the Sea and solidifies an apparently disparate collection of elements into a tight uniform geometry. Implied triangles in the composition of Western paintings has a long tradition which Rosa Bonheur clearly understood and used to great effect.

Sheep by the Sea seems at first a fairly simple and straightforward painting. However, with further attention, it reveals a grandeur and vitality that appeals to the viewer. It presents the beauty and innocence of these familiar domestic animals within a realistic and natural habitat. Rosa Bonheur was famous for depicting her animals with naturalistic accuracy. She achieved this polished illusion through scientific observation and knowledge gained from her extensive visits to farms and slaughterhouses. At these locations, she created many preparatory sketches of the animals’ anatomy through direct observation and surgeon-like skill. Rosa Bonheur was a realist, but most importantly, she was a naturalist. She believed that by understanding the muscles, bones, and ligatures of the animals’ physiology, she could effectively capture the animals’ masses in her paintings. Bonheur captures the sheep’s biology perfectly in Sheep by the Sea. She plays with light and shade over the wooly subjects and therefore gives them physical form and soft texture.

Rosa Bonheur admired the style of French painter, Théodore Géricault, who is probably most famous for his The Raft of the Medusa painted in 1819. Bonheur appreciated his use of dramatic lighting, loose brushstrokes, and rolling skies. These elements are clearly seen in Sheep by the Sea, however, unlike Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, there is a dramatic lack of action. There is not a riot of activity and frenzy. Sheep by the Sea does not explore the drama and heroism of modern life. It explores a placid moment found in any time and place when domestic animals lie to rest. While Rosa Bonheur painted Sheep by the Sea in 1865, there is nothing in the subject matter indicating it is 1865. Yes, the artistic style is indicative of a mid-19th century painting, but the subject of seeing sheep in a field could easily have been observed in any time period.

The landscape presented in Sheep by the Sea is essentially timeless without a specific hint to the year or century. However, the horizontal direction of sunlight does hint at a specific time of day. The viewer is observing either early morning or early evening when sheep are typically out in the fields grazing. Since the animals in Sheep by the Sea sit placidly upon the meadow lawn and have an almost “food coma” lethargy, the sheep may be happily resting after a day’s nibble of grass. Thus, the lighting and animals’ behavior indicate a late afternoon or early evening time of day in Sheep by the Sea.

One of the reasons Rosa Bonheur was such a successful artist is because of the love and admiration emanating from her images. She really granted a sense of life to her animals. Even when the animals are not in action, as in Sheep by the Sea, there is still a physical presence felt. The foreground of Sheep by the Sea has a lush meadow between the viewer and the three sheep that unifies the viewer with the subject. The thick brushstrokes imply a healthy growth of vegetation that echoes the thick curls of hair in the sheeps’ coats. They are healthy sheep in a healthy landscape. The life forces of animals and plants fill the scene.

Rosa Bonheur was inspired to paint Sheep by the Sea after a visit to the Scottish Highlands in 1855. She used this decade’s old inspiration to great success when Sheep by the Sea was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1867 before entering Empress Eugénie’s private collection. Sentimental paintings of domestic animals were very popular among the upper classes in both England and France, and Sheep by the Sea is definitely a sentimental image. It evokes the tenderhearted legacy established by previous French artists like Jean-Baptiste Greuze and François Boucher and solidified by contemporary artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Rosa Bonheur used her artistic prowess to capture the public and to promote her own success and female empowerment. Bonheur believed that female empowerment was the cornerstone for a new and better society, and if she were alive today, she would have been considered a feminist as she constantly challenged the male-dominated status quo.

Rosa Bonheur’s Sheep by the Sea is not a large painting. It is only 13 in high and 18 in wide (32 cm high and 46 cm wide). However, it represents larger and more universal ideas not contained within its small size. It announces scientific observation, sentimental emotion, feminine empowerment, and female patronage. It combines thinking and feeling into something pleasurable for both the rational and irrational. This complex image is painted on a panel, and it hangs within the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC, USA. It joins other examples of feminine artistic achievement which is- thankfully- finally being reevaluated and recognized. As the sun shines in Sheep by the Sea, the sun never sets on the Bonheur empire.

Works Referenced:

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!